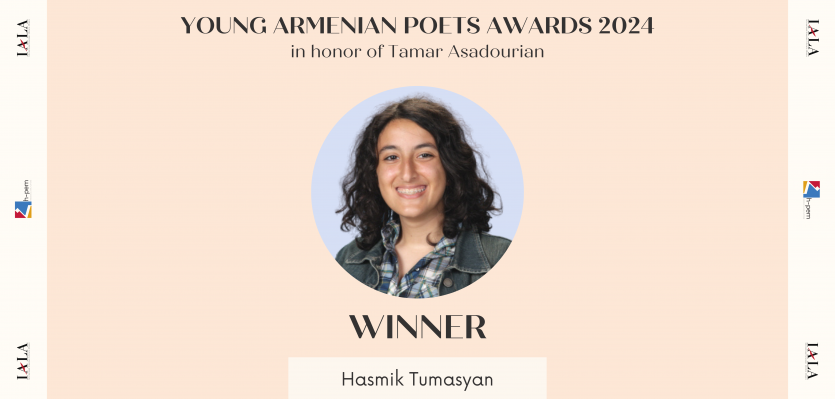

Poem | home is a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on lavash bread by YAPA 2024 Winner Hasmik Tumasyan

October 01, 2024

Read "home is a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on lavash bread" by YAPA 2024 Winner Hasmik Tumasyan, a 17-year-old Armenian-American writer from Southern California, with commentary from YAPA Judge Raffie Joe Wartanian.

home is a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on lavash bread

sweet like chocolate chip cookies and pomegranate seeds and hugs from jetlagged relatives who just got off fourteen hour flights. salty, crunchy (because my mom is convinced it’s healthier), seeping from either side of the makeshift roll.

my tatik stacks lavash on top of itself

and cuts it into neat slices every time.

i rip off scraps whenever i need them

with all the rugged individualism of the American Dream. a kind of free-spiritedness that might’ve been appreciated at Boston Harbor,

not so much at the table.

my pb&j is made on lavash speckled with tonir spots

because white bread feels wrong.

my jelly is actually apricot preserve

because real jelly doesn’t feel real.

sweet like the highlands. sweet like jan.

sweet like gas station donuts. sweet like the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock.

the salt stings lovingly –

an innocent laugh at my unrolled “r’s,”

that distinctly Armenian tyranny.

that distinctly American apathy.

Hasmik Tumasyan is a 17-year-old Armenian-American writer from Southern California. She enjoys writing poetry, prose, and screenplays. Most of her inspiration comes from fantasy media and cultural experiences.

YAPA Judge Raffi Joe Wartanian on Tumasyan’s “home is a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on lavash bread”:

“The poet behind “home is a peanut butter and jelly sandwich on lavash bread” utilizes the pb&j as a lens into an identity shaped by Armenian and American influences. These influences are juxtaposed from the first line exploring the sandwich’s sweetness through the American staple of a “chocolate chip cookie” and the Armenian staple of the “pomegranate seed.” And later, “sweet like jan” is a subtle, subversive word play demonstrating how just one letter–not jam, but jan–can evoke a world of difference. Extending the exploration likens sweetness to “hugs from / jetlagged relatives who just got off fourteen hour flights.” A synesthetic insight emerges as taste and touch intermingle, mirroring the writers’ own meditation on the intermingling of two identities. Family surrounding food allows the writer to bring the mother, who is “convinced” that crunchy peanut butter is “healthier,” and the tatik (grandmother), who “stacks lavash on top of itself / and cuts it into neat slices every time.” Imagery of the sandwich’s preparation allows the writer to characterize family while providing a visual of the pb&j “made on lavash speckled with tonir spots.” Initially, this suggests an Armenian exterior of lavash, with an American interior of ingredients, but in the second stanza, the interior’s essence is complicated: “my jelly is actually apricot preserve / because real jelly doesn’t feel real.” The use of apricot preserve, made of organic ingredients, rather than “real jelly,” made of synthetic preservatives, heightens the tension surrounding the sandwich and the nature of the writer’s identity: one organic and naturally occurring, the other an amalgam of chemicals and corn syrups. And if “real jelly” is mostly artificial, then what does that suggest about American identity? Without being pedantic, the writer gently gestured toward this provocative question while giving readers the agency to grapple with the nature of Americanness. Yet the writer is careful not to romanticize Armenian identity: “an innocent laugh at my unrolled ‘r’s’ / that distinctly Armenian tyranny / that distinctly American apathy.” These closing lines depict the despotic tones that can sometimes render burdensome the preservation of a fragile people, contrasted against the privilege of indifference that arises in a global empire. Structurally, the poem’s two stanzas both play with notions of sweetness, preparation, and cultural tropes, but in different orders and with distinct sensibilities. This choice contributes to a sense of “cohesion and coherence” (Williams) bridging the two stanzas, like the two ingredients of the sandwich, like the two pillars of a hyphenated self, like the countless ways this poem can be read and re-read, revealing something new and rewarding each time.”

Raffi Joe Wartanian is a writer, musician, and educator who teaches writing at UCLA and serves as the inaugural Poet Laureate in the City of Glendale, California. His essays have appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, University of Texas Press, Miami Herald, The Baltimore Sun, Lapham’s Quarterly, Outside Magazine, and elsewhere; and his poetry has appeared in The Los Angeles Press, No Dear Magazine, The Poetry Lighthouse, Armenian Poetry Project, LAdige, Ararat Magazine, and beyond. Raffi has taught writing to veterans at the Manhattan VA, incarcerated writers at Rikers Island, youth in Armenia, and undergraduates at Columbia University, where he earned an MFA in Writing. He is the recipient of grants and fellowships from The Fulbright Program, Eurasia Partnership Foundation, and Humanity in Action. As a musician, Raffi has released two albums of original compositions: Critical Distance and Pushkin Street. Recent commissions include film trailer music for The Tale of King Crab, and a soundtrack for a production of William Saroyan’s Pulitzer-winning drama The Time Of Your Life staged by the UCLA Department of Theater.

Any additional references or recommendations? We would love to hear your suggestions!

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!