Hye Kin: The untold story of Armenian women’s resistance

November 01, 2018

Once important figures aside historic fedayis (guerrilla fighters), Armenian women are often left out of our stories of resistance. Delving into this history, we can see that they had major roles as writers, political activists, and revolutionaries, and that Armenian women continue in this tradition of resistance today. In Armenia’s regions under direct military threat, they are the backbone of a non-violent resistance movement supporting military action and forging new paths to Armenian strength and unity.

What is our story missing?

As Armenians, we look to history to inspire our fight for survival. Musicians play ancient folk songs, historic monuments fuel tourism, and soldiers are inspired by past fedayis. But the narrative of Armenian resistance is lacking the substance of the full society that supported and motivated its military action. Notably, it is lacking women.

It is not, however, lacking female participants. A project by professors Melissa Bilal and Lerna Ekmekcioglu traces women’s role in the 19th century Armenian Revolutionary movement. It brings forward women like Mari Beylerian, who advocated for the rights of women and Ottoman Armenians in protests, articles, short stories, and poetry, and Haykanoush Mark, who published «Հայ Կին» ("Hye Kin," which is Armenian for "Armenian Woman"), a prominent feminist journal, that included everything from news on feminist conferences to that of the orphans and other victims of the Armenian Genocide. These women were central to creating today’s Armenia, but our narratives erase them from history. Which begs the question: what is our story missing today?

The two regions of Armenia under immediate military threat, Artsakh and the border with Azerbaijan in Tavush province, have developed a strong non-violent resistance movement. Led by women, it operates in fields like business, art, and education, allowing people to live and thrive in these communities, without which the military would have nothing to defend. It is one of the only things standing between modern Armenia and the powers that would destroy it.

The women highlighted in this photography series are redefining the Armenian resistance as something that we all take part in. They are creating the unity we need to survive.

Text by Araxie Cass.

Photos by Kristin Anahit Cass.

Ruzanna

Ruzanna Avagyan is one of the thousands of Armenians refugees from the city of Sumgait in Azerbaijan, where her father saw Azeris cut open a pregnant family member’s stomach and burn her alive. She survived thanks to Azeri friends and language skills that got her to Yerevan.

“We loved Azerbaijan; it was our home,” she said.

In Yerevan, Ruzanna organized hunger strikes and other protests advocating for Artsakh’s independence. Artsakh’s refugees weren’t internationally recognized, denying them the help that allows others to start over. Ruzanna now leads Artsakh’s refugee organization, which connects refugees still struggling with health, housing, and financial issues with government agencies and NGOs.

“We’re not looking for bread, we just want recognition and education,” she said.

Ruzanna has also participated in peacebuilding. She saw some success, but the Aliyev government closed down programs, inhibiting future progress. Even so, she keeps in contact with classmates from Azerbaijan across the border and politics that separate them.

Anahit

Anahit Nazaryan is a project manager in Yerevan, but she spends her weekends driving to Tavush’s border region to surprise people at their homes and see how their small businesses are progressing. These monitoring visits are part of Sahman, an NGO that she runs with four other friends: two from Yerevan, one from Ireland, and one from Lebanon. Three of the friends started Sahman after a trip to one of the border villages shocked them into action.

The organization started small, crowdfunding to help villagers build greenhouses for more efficient agriculture, but now supports projects from stone cutting to textile production. They evaluate villagers’ ideas for potential and sustainability and support them with equipment, as well as business coaching that empowers them to succeed.

“All of the business owners have some of their own investment in it, as well,” she said. “Through this, and surprise monitoring visits, we make sure that the equipment is being used well. If it is not, we will take it back, which we have had to do once.”

Lusine

Liana’s sister, Lusine, has a master’s in Human Rights and is an activist living in Yerevan.

“It’s an inner conflict,” she says, “I want to live in my hometown and do something for the people, but I also want my own career.”

Lusine is a member of the international anti-war group, “Women in Black,” and brings their ideas and training to the border. After an Italian peacebuilding program with Azeri women, she organized an art exhibit of young people’s representations of peace, matched with a photo exhibition by an Azeri participant.

“Hundreds of exhibitions will not make progress on their own,” she says. “So, I also work with the artists to help them become active leaders in political and social life.”

Lusine looks to the future, with ideas like connecting NGOs and activists, and bringing her colleagues to Berd as mentors.

“After the revolution, people started to believe in themselves,” she said. “It is not a dead place here anymore; people are confident in their strength.”

Hasmik

Hasmik Azibekyan leads a majority-female team at the Center for Community Development (CCD) in the border town of Noyemberyan. They engage in an unconventional resistance: building a dairy where farmers will take their milk to be made into cheese and butter in a region where few have the resources to do so themselves. The dairy will reach across borders, exporting to Russia, and inviting tourists with a tasting room.

Hasmik works tirelessly on CCD’s many projects, including regional job fairs, tourism, and producing quinoa for sale to the Ministry of Defense. They bring money into the region from USAID and other organizations to create these sustainable projects and get people working.

“The border does not have to hold back our economy,” she said. “In Noyemberyan, it is very calm and safe, so if there were opportunities, people could come back from Yerevan and Russia. We want to be an example to people. If they want to have success, they need to work.”

Zhanna

For 20 years, Zhanna Grigorova was a journalist, active in politics and peacebuilding. She worked for Artsakh’s government in its early years, and traveled throughout the Caucasus. But eventually, she started to feel like she was running on a wheel, and went for a change, following her passion to teach European Literature at Artsakh’s Mashtots University. Noticing a declining appreciation for literature, she was inspired to bring words to life through performance. With her students, she put on a play based on an underground group of poets and artists before the Russian Revolution. The show was a success and grew into the two theatre troupes that she runs today.

Zhanna’s plays are in Russian, attesting to Artsakh’s population of native Armenians and those from Russia and parts of Azerbaijan, that make its dialect a mix of Armenian and Russian. Zhanna uses theater to teach cultural appreciation and leadership skills essential to Artsakh’s success.

“You cannot develop a state only through selling petroleum or gold. The people must develop with good theater, music, art, and culture,” she says.

Liana

Liana Kosakyan teaches history less than a kilometer from the border, sacrificing opportunities in the capital for her home region. Her school is smattered with bullet holes, and a blast wall hides it from the Azeri soldiers who used it as a training target.

“I think the students in this conflict zone must have a chance to work and be taught by professionals, ” she says. She engages with history, exhibiting 400+year-old pots from the village in the school, and modern realities through peacebuilding activities, such as a conference with Turkish teachers.

“We showed them a film about what is happening on the border,” she said. “None of them could watch until the end. They said “Turkey is not Azerbaijan,” but we replied that Turkey supports Azerbaijan. We want to show them that it is their job to show reality. But it’s difficult because they are not free to say it in schools.”

“But here,” she continued, “We are free. We don’t teach our kids to hate; we teach them to be leaders.”

Nune

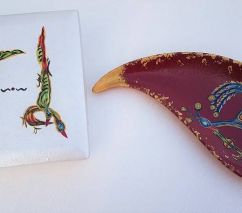

Nune Azizyan married in Noyemberyan, leaving her job as an economic manager in Yerevan. Looking for things to do, she joined a 3D modeling class. A few years later, she runs a business, selling painted lamps and vases with her former teacher.

Nune is also a leader in Tavush’s strong environmental movement that took off when mining company, Polymetal International, announced plans for strip-mining in Noyemberyan.

“I was pregnant at the time, so I couldn’t go out and protest. But I started a petition and collected 300 signatures. We presented it to the municipality, who told the company, ‘no, we want to develop eco-tourism instead.’”

Following that promise, Nune started the Noyemberyan Tourism Center, which distributes information and organizes guides and events. She and a group of others produced a video, urging people to stop littering, and are working on other ways to engage their community in environmental protection.

“Noyemberyan is not only a place where people live in fear,” she said. “We have things to show here.”

The threat and response in Artsakh differ from Tavush. Artsakh is an independent republic with a stronger military presence and government initiative to develop the state and its society.

Karine

Karine was a soldier in Artsakh’s war for independence.

“I broke the wall,” she said. “When I met the commander, he told me to go home and bring a son. I said, ‘Is this only the men’s homeland and not ours? I am the man in my family.’”

The commander challenged Karine to assemble a Kalashnikov in under a minute, and she did. She was the only woman in the beginning of her service, but was joined by many more.

“The men said they didn’t need us, but when we were there, they fought stronger.”

Karine was injured in battle and spent 17 days in a coma in the hospital. Karine’s mother resisted advice from doctors, and opted to treat her daughter with a local remedy of Artsakh honey, which she learned from consulting other doctors. Today, they live together, embodying the partnership of military and nonviolent resistance that sustains their country.

“I am happy that our children are growing up without fear, speaking Armenian and thinking of peace.”

Lilit

Less than a year after completing Artsakh’s Tumo technology education program, Lilit Sogomonyan and her classmates started a web design company. She is a programmer and head of the company, working on orders from businesses like restaurants and internet stores in Artsakh and abroad.

“Many companies must grow so that Artsakh becomes a tech center and people know its name,” she said.

Lilit is in her final year of studying math in university and teaches three different technology education programs in Stepanakert and underserved rural areas. Students work on traditional technologies, like websites and games, but their work has also been instrumental in developing drones and other military technology.

Lilit is optimistic about her work and the role of women in tech development. She sees many women in tech fields, and noted that her entire university math class is female.

“The chief of this IT center is a woman, as well as the minister of education and the chief of the state university. Women can do a lot in tech here.”

Though Armenia’s nonviolent resistance movements are based in the regions, its success requires the cooperation of Armenians in Yerevan and the diaspora.

Larissa

Larissa Hovhannisyan grew up in the United States. After college, struggling to discover who she was and what she wanted to do, she joined Teach for America. She worked with special education in Arizona for two years.

“It changed my life completely,” she said. “And then I wondered, why don’t we have this in Armenia?”

Larissa answered her own question by moving to Armenia with nothing but her idea and contacting Teach for All, which helped her start-up. Teach for Armenia began with 13 teaching fellows in villages around Armenia, and now have 61. They place a special focus on the border villages and have just started a chapter in Artsakh.

Due to the concentration of resources in Yerevan, rural areas often feel forgotten, but Larissa hopes to show parents that not all is lost. Fellows come from all regions of Armenia, as well as the diaspora, engaging a wide group of Armenians in strengthening their homeland through education.

“I’m a grounded idealist,” she says.

(Photos: Kristin Anahit Cass)

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!