The Nativity: 8 hidden facts in the magic of medieval Armenian art

January 06, 2021

The birth of Jesus has been a recurring theme for Armenian artists since early times. Depictions of the nativity in medieval Armenian art, especially in miniature painting, are full of religious symbolism. Based on the nativity narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, they combine traditional approaches to iconography with diverse artistic mediums and common cultural elements.

Since ancient times Christianity has extended its influence to culture and the arts both in the East and the West. Artists have explored the life of Christ in a personal way, to develop their own philosophy based on a commitment to Christian teachings. In their efforts to meet the need of the society for religious images, they have galvanized major movements in art, in full-blown inventiveness.

The iconographic portrayal of the birth of Christ, a widespread feature in Christian art, has been a source of creative inspiration for many centuries. The nativity of Jesus— Surp Dsnund | Սուրբ Ծնունդ, celebrated throughout the Christian world as Christmas, has found creative expression in Armenian art since 301, when Christianity was adopted as the official religion in Armenia, a decade before it was tolerated in the Roman Empire.

The 6th century miniature painting of "The Adoration of the Magi" attached to a 10th century Etchmiadzin Gospel, as well as the bas-relief sculptures of the famous funerary monument at the Odzun church (5th–6th centuries), are among the earliest representations of the nativity in Armenian art. Outstanding Armenian miniaturists such as Toros Roslin and Grigor Tsaghkogh are most celebrated for their depictions of the subject. The 10th century frescoes of the Church of the Holy Cross on Akhtamar Island in Lake Van, are considered gems to be treasured.

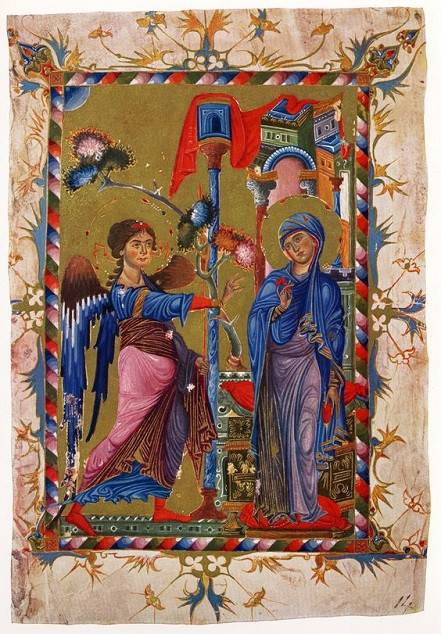

The Annunciation

In Armenian miniature painting the nativity scene is generally preceded by the Annunciation, marking the angel Gabriel’s visit to Virgin Mary. It is followed by the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (commemorated by the Feast of the Purification of Virgin Mary, also known as Candlemas) and the Baptism of Jesus. Since the Armenian Church celebrates both the birth and baptism of Jesus on January 6, sometimes the nativity is followed directly by the baptism.

Interesting fact: Note Mary's almost sensual pose.

(Miniature painting: Attributed to Toros Roslin, a 13th century Gospel illuminated in Cilicia. Armenian Miniature Painting, Yerevan, 1969).

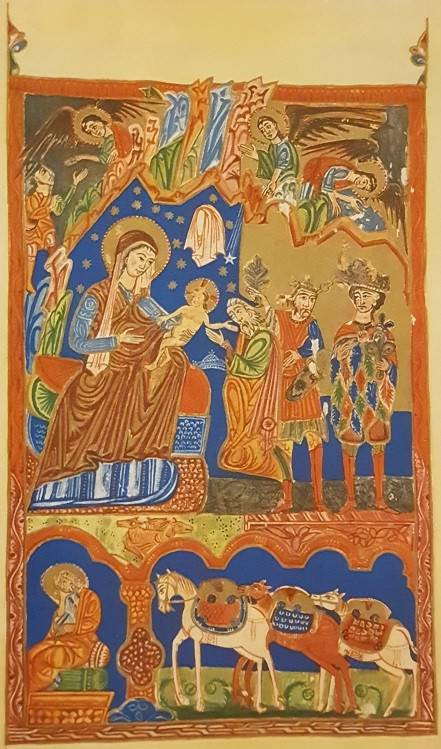

The manger

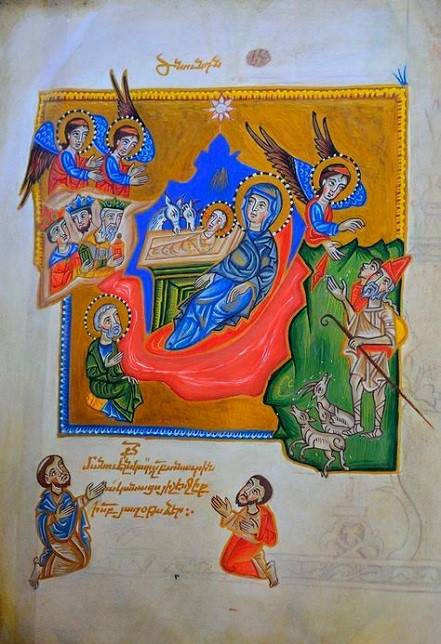

According to tradition, the site of the nativity was a cave near Bethlehem. In Armenian medieval art, the infant Jesus is usually at the center of the composition, which includes Virgin Mary, her husband Joseph, the midwife Eve, the angels which appear above the cave and look down at the manger, the shepherds accompanied by sheep, and the Magi who have come to worship the newborn child.

Interesting fact: Fused with a vivid color palette, golden hues, and expressive silhouettes, the painting shows signs of Western European influence.

(Miniature painting: From a mass-book painted in the city of Ardske in the Western Armenian province of Vaspurakan, 1460. Armenian Miniature Painting, Yerevan, 1969)

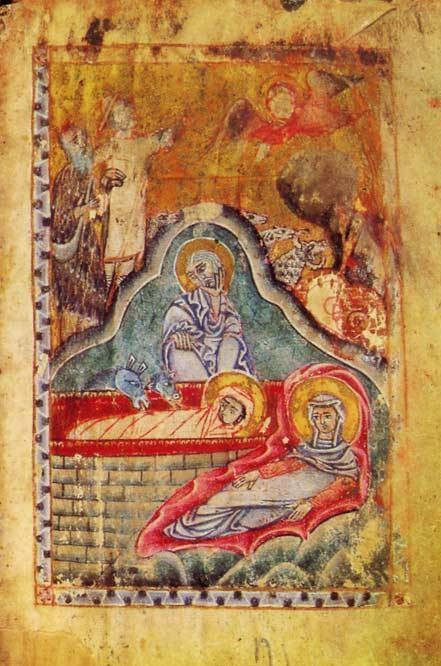

The infant Jesus

The Holy Child lies in a manger inside the famous Bethlehem cave, naked or wrapped in swaddling clothes, with Virgin Mary by his side. In some depictions, the manger is also an altar. Both the manger and the swaddling clothes can symbolize sacrifice, which is why in Armenian iconography the swaddling clothes rather resemble a shroud.

Interesting fact: Two animals, typically an ox and a donkey, can be spotted close to the manger. Although there is no mention of this in the Bible, it is believed that the breath of the animals provided warmth for the newborn Jesus.

(Miniature painting: "The Nativity and St Joseph," by Momik, 1302, Noravank, Matenadaran collection. shnorhali.com)

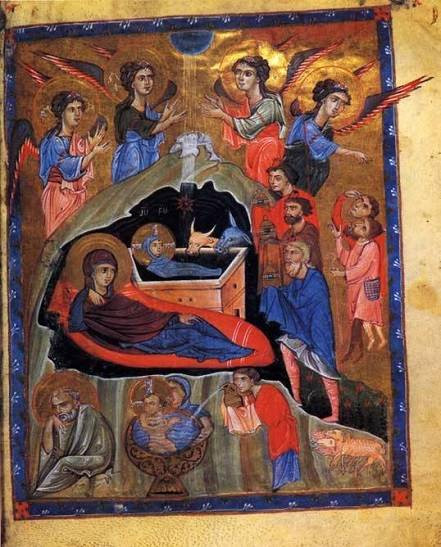

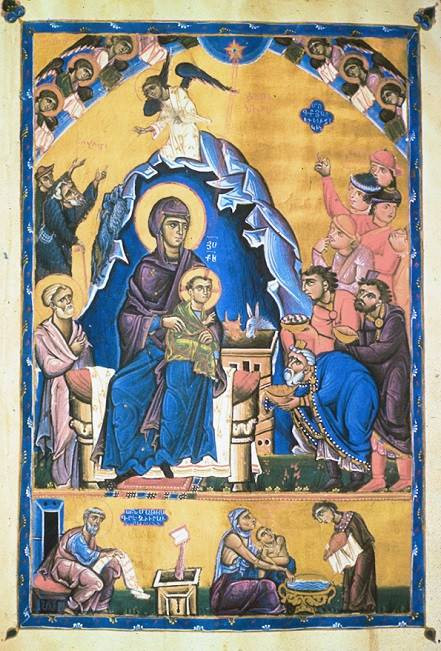

Virgin Mary

Virgin Mary is normally portrayed either sitting or leaning against a red pillow which signifies a royal throne. Her resting pose or her facial expression signal her exhaustion after childbirth. Red is also associated with her clothing, as if she serves as the throne for Christ the Savior.

Interesting fact: The artist was praised for his "ability to convey deep emotion without undue emphasis."

(Miniature painting: "The Nativity," by Toros Roslin, Malatia Gospels, 1268, Hromkla monastery, Matenadaran collection. shnorhali.com)

Joseph

Joseph and Eve are usually painted at the very bottom of the painting. Joseph is in isolation, which emphasizes the fact that he was not Jesus’ father. He can sometimes be seen in a pensive mood with his back turned towards the rest. Next to Joseph, Eve can be observed bathing the infant Jesus either alone or with the help of a midwife. Holding the child in one arm, she checks the temperature of the water. By assisting Mary to give birth and bathing the infant Jesus, Eve is receiving atonement for her sins.

Interesting fact: The scene was painted during the Mongol invasions of Armenia, and synthesizes the whole gamut of past creative practices.

(Miniature painting: Attributed to Grigor Tsaghkogh, the Translators' Gospel, 1232. Armenian Miniature Painting, Yerevan, 1969).

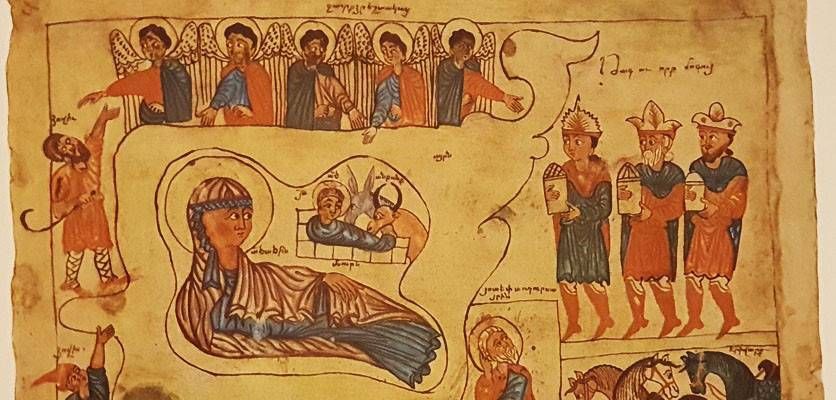

The Star of Bethlehem

According to the Christian tradition, the Magi or “the wise men from the East,” guided by the Star of Bethlehem, traveled from afar to visit the newborn Jesus. Armenian masters rarely left out the Star of Bethlehem from the pictorial representation of the nativity. The star is either depicted inside the cave, above the manger, with its luminous rays stretching to the sky to indicate the trajectory it had passed, or it is placed in the sky, right above the cave, as its rays fall on the manger.

Interesting fact: The star of Bethlehem consists of three rays symbolizing the Holy Trinity. Angels flank the rays on either sides.

(Miniature painting: "Adoration of the Magi, the Nativity of our Lord," by Aristakes Tzeruni, Aghtamar Gospels, 1391, Aghtamar, Lake Van, Matenadaran collection. shnorhali.com)

The shepherds

Angels brought news of Christ’s birth to shepherds who lived near the manger. In iconographic depictions one of the angels faces the shepherds, as if announcing the birth of the savior. One of the shepherds can sometimes be seen playing the flute, thus accompanying the angelic benediction. In certain depictions, some of the shepherds hold a sheep or a lamb in their arms as an offering to the Holy Child.

Interesting fact: Sargis Pitsak created this painting in tragic times, when the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was plagued with epidemics and wars. He was the last great miniaturist to illuminate manuscripts in independent Cilicia.

(Miniature painting: "The Nativity of our Lord," by Sargis Pitzak, 1336, Sis, Cilicia, Matenadaran collection. shnorhali.com)

The wise men from the East

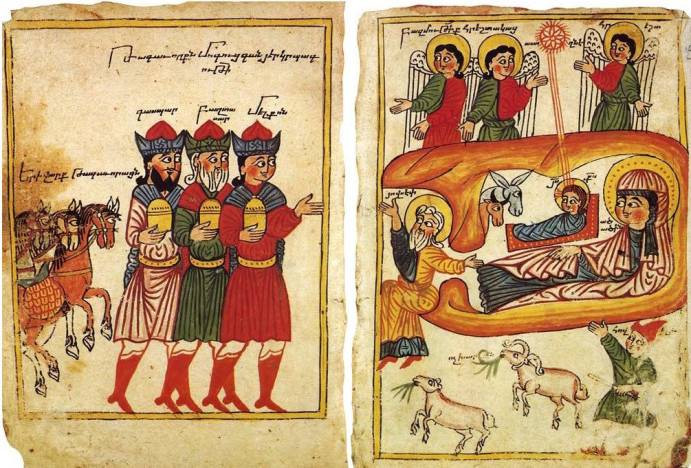

Spiritual connotation and symbolism are associated with the Magi and the gifts they bear. As a sign of worship, they bring gold, frankincense and myrrh, each of which is related to specific symbols. Gold symbolizes Christ’s kingship on earth, frankincense denotes his deity, while myrrh, which was used in the Ancient Orient as embalming oil, represents death (as Jesus died on the cross for the salvation of mankind). The Magi are painted holding a treasure box containing their offerings.

In some representations, the names of each of the Magi are written above them. They almost always appear in three at the entrance of the cave (sometimes the eldest of them is already inside the cave). The number three stands for the three stages of life: infancy, adulthood, and old age, as well as the three nations that descended from the sons of Noah. Thus, the presence of the Magi signifies that humans of all ages and nations bowed down before the Holy Child. Armenian artists stayed true to this symbolism and painted the Magi not only with facial features highlighting their different ages, but also in different costumes.

Interesting fact: Since the Magi came from the East, the artist has depicted them with Mongol bodyguards.

(Miniature painting: "Adoration of the Magi," by Toros Roslin, Gospel of Hromkla, 1260, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem. shnorhali.com)

Sources:

http://echmiadzin.asj-oa.am/5129/1/93-102.pdf

https://www.shoghakat.am/am/telecasts/2772

L. A. Dournovo (1969). Հայկական մանրանկարչութիւն [Armenian Miniature Painting] . Matenadaran (in Armenian)

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!