Understanding ‘Anush’: A second look at Tumanian’s great heroine

March 01, 2019

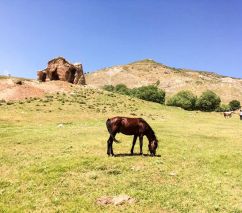

It is often said that literature is the most accessible way to see the world—and worlds beyond our own. Growing up outside of the traditional diaspora, there were few opportunities to tap into my Armenian roots. The stories of Armenia’s national poet, Hovhannes Tumanian, were my window into the unfamiliar lands of my forefathers. Last summer, my family and I ventured to two of the writer’s former homes, to see what inspired the man who inspired generations.

Yerevan, summer 2004

The night is still. Everyone is sleeping except for mama and I. Tomorrow, we will attend a performance of “Anush,” based on the late 19th-century poem written by Hovhannes Tumanian, Armenia’s most beloved writer. It is the first and only Armenian opera to be centered explicitly on Armenian folklore, I am repeatedly told. Though the plot was unknown to me, the review felt familiar. “first” and “only:” we are drawn to words that denote our exceptionalism, even if there is no purpose or substance behind them.

Tonight, mom is my storyteller. When she reaches the climactic end, I blurt out, “this is just the Armenian version of Romeo and Juliet!” Nothing about this quintessentially Armenian tale seemed particularly unique or exciting to my 11-year-old self.

I hoped that the next day’s performance would offer some clarity, but as with most operas, I did not understand a word—though the chorus of the song, “From Under the Clouds,” was catchy and I found myself humming along to it as we exited the concert hall. Alas, I did not see the allure of the Great Tumanian and his star-crossed lovers. For the rest of the summer, I feigned excitement whenever anyone brought up Anush and her Saro, and their esteemed creator.

USA, the noughties

Despite vibrant summers spent in the homeland of my parents, my childhood was filled with only fragments of Armenianness—from phonetically memorizing lines of the poem, “The Dog and the Cat” for a Saturday school class, to an over-animated Sunday school performance of “The Death of Kikos,” (the brief extent of my acting career), to bedtime with mama, under a dim light, reading fairy tales of Armenian warriors and princesses, peasants and farmers, overcoming the impossible in faraway lands. She’d recite the same lines over and over again in our sleepy suburb until my mind carried away the images relayed by her tongue.

Most of her tales came from one of the few possessions she brought with her from Armenia: a worn-out collection of children’s short stories; precious and delicate, like an ancient manuscript in a museum, just pressing on the tattered sheets too hard could tear the whole thing apart. I can’t recall a single line from this book now, but at the time, it was the bible to my otherwise secular, sanitized childhood.

I didn’t realize until much later that the author of these stories was none other than Hovhannes Tumanian. In an ironic twist, the man whose genius I had rejected years before was, all along, the cultivator of my Armenian identity in the diaspora.

Tumanian the trailblazer

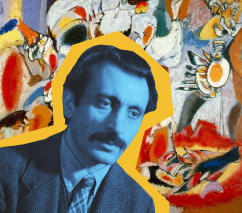

Regarded as one of Armenia’s best storytellers, Tumanian had one of those affable faces, with a kind smile shrouded by a luscious beard that could make any hipster today green with envy. Living in a time of intense conflict—marred by wars, genocide, displacement, and starvation—he drew on his creative talent to inspire those suffering around him, while promoting peaceful coexistence. Like a sage old man, he doled out lessons on love and morality, disguised as make-believe tales and far-fetched fables.

Because many of his writings center on universal themes using simplistic language, which often appeal to the youngest and most impressionable of audiences, some may make the mistake of labeling Tumanian a child author. But his appeal went far beyond age demographics—or really any definable distinctions.

Breaking from the archetypal tragic hero and the archaic formalities of his predecessors, Tumanian elevated common folk from side pieces to protagonists and antiheroes. His prose—based on the dialect of his mountain village—is simple and reflective of how Armenian society spoke at the time. He drew on classical Armenian folktales and songs and recreated them for contemporary audiences. In Tumanian’s world, anyone could be the hero of their own story, and everyone—regardless of class, age, ethnicity, or gender—deserves the right to access these narratives. Nearly a century after his death, no writer since has left such an indelible impression on Armenian literature.

Though much has been said about Tumanian’s writing and activism, I wondered how this transcendent literary giant—known for his disdain of traveling—became the author of my greatest literary adventures growing up. This summer, my family and I decided to find out, by embarking on an adventure of our own.

Yerevan, May 18, 2018

My family arrived in Yerevan on International Museum Day. Every year on this date, avid tourists and art buffs flood the city streets to embark on a free museum crawl into the late hours of the night. Our first destination was the Hovhannes Tumanian House Museum. Pushing through hordes, we came across a room filled with century-old furniture, showcases lined with original poster advertisements for film and play productions of his novels, and—most curiously of all—a 3D hologram of Tumanian, walking around and reading a newspaper.

Though we came face-to-face (sort of) with our writer, the experience lacked the intimacy we were seeking. Once again, I found myself turned off by the imagery of Tumanian the Great, without conveying the very essence of what made him so exceptional. And so, we set our sights on another of the writer’s house museums, in the hope of discovering the man behind the hologram.

Tiflis, May 23, 2018

There is much to be said about Tbilisi, or “Tiflis,” the once-spirited Armenian metropolis and home to many great Armenian intellectuals, artists, and writers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. My family and I embarked on a journey to this enrapturing bygone of Armenian opulence by paying a visit to the home of one of the city’s finest residents.

After years of proposed demolition and a strong public awareness campaign from Armenians in Georgia and Armenia, the Hovhannes Tumanian scientific-cultural center opened its doors last August in a grand ceremony. “It was a lot of work to save this house,” director of the center, Gisane Hovsepyan, tells us. Tumanian lived here for 14 years, where he created some of his most well-known classics, including the opera adaptation of “Anush.”

The house is in amazing condition, especially considering the state of the other buildings in the area, but its collection remains scant; many of the household items were transported to the house museum in Yerevan years ago, so most everything here is a recreation, and not an original, from the writer’s time. Coming across our last artifact, however, we were delighted to hear that it was a genuine Tumanian holdover. Tucked into the corner of the main hall was a black Victorian dresser with a gigantic, splendid mirror.

In the summer of 2017, my family snapped a photo of our reflection through one of the life-sized mirrors in the Palace of Versailles; it was one of those silly, innocuous things families do when they travel abroad. Unable to resist the opportunity for another embarrassing family moment, we ended our tour at Chez Tumanian with a quick pose, forever imprinting our faces on the home of our poet.

There was no hologram to be found here; Tumanian’s face did not pop out of the mirror to greet (or, more likely, chide) us. Yet, here, one could picture our silver-haired raconteur, combing his pointy beard and flashing his warm smile to his myriad house guests. And, just as easily, one could make out Levon Shant and Avetik Isahakian and Nikol Aghbalian—the Who’s Who of prolific, accomplished Armenians of the time—gathering in these hallowed halls, (as depicted in Soviet Armenian painter, Dmitry Nalbandian’s, famous painting), crowded around the piano, watching Komitas perform a tune.

For nearly a decade, Armenian intellectuals from all walks of life would gather in Tumanian’s garret twice a week to discuss literature, art, and politics. This group, aptly called Vernatun (garret), would share their criticisms and perspectives in a quasi-book-club-meets-parliament house, leaving an indelible, unquantifiable mark on Armenian history, culture, and production. A part of me felt like we were invading this space, like time traveling characters in a mystery novel, but a greater part felt like this is exactly what our author would have wanted.

From the palace of French kings to the third floor walk-up of a rags-to-riches Armenian writer, our cheeky acts read like scenes from one of Tumanian’s stories. But, I will avoid putting words in our writer’s mouth, lest I make—in his words—a “drop of honey” out of a sticky situation.

Ush lini, Anush lini

Despite the tumultuous times he lived in and the horrors he witnessed mankind commit against one another, Tumanian never lost sight of the beauty of people and nature, the simplicity of kindness and authenticity, and the power of fables and rhyme. Perhaps this is where his true superpower lies, and the reason for his enduring legacy that continues to mystify and entrance his beloved fans, nearly a century after his premature passing.

Over a decade after that lackluster performance in the Yerevan Opera Theater, and a few weeks after inviting myself into not one, but two, of the writer’s homes, it was time to give “Anush” another shot—this time, the poem, not the opera. In my bedroom, by a dim light, I opened my tattered book and entered the world of “Anush”—for the first time. The night came alive with scenes of wedding fights, forbidden encounters, the sun setting on a quiet village, and a young girl, dejected and cornered, casting her fate into the pits of a waterfall.

As dusk turned to dawn, my feelings on the assessment of my 11-year-old self could be summarized in a Tumanian-esque rhyme of my own: “Vush vush, Anush… How could I be so obtuse?”

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!