From 2018 to 1918: Traversing through time in Tiflis

September 25, 2018

For centuries, Georgia (the country, not the U.S state) held a special place in the hearts of many Armenians. Her capital, Tbilisi (or “Tiflis” as it’s known to Armenians), was, not too long ago, a major center of Armenian cosmopolitan life, where Eastern Armenian culture, literature, and political life flourished. This summer, my family and I decided to check out what’s left of her Armenian past. In just a day and a half, we too fell in this love with this enchanting city, and realized that she still has so much more to offer.

The city more Armenian than Yerevan

.JPG) “Kartlis Deda,” or "Mother of a Georgian,” keeps watch over her capital. Many have compared her to Yerevan’s “Mother Armenia” monument statue.

“Kartlis Deda,” or "Mother of a Georgian,” keeps watch over her capital. Many have compared her to Yerevan’s “Mother Armenia” monument statue.From the Byzantines and Ottomans to the Persians and Soviets, Armenian history is a storybook with countless antagonists. Conquerors came and went, their empires rising and falling like dominoes, and, all the while, borderlines drawn and redrawn, erased and shifted, at fervent speed. For over 500 years, Armenians lived under foreign rulers, with no state or empire of their own. Yet, this did not stop them from shaping the lands they lived on.

As a result, Armenians often joke that the capitals of their neighboring countries are "more Armenian" than Yerevan, the capital of today’s Republic of Armenia. Though few Armenians remain in Tiflis, Bolis (today’s Istanbul), and Baku (the capitals of present-day Georgia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan respectively), the scope of Armenian influence—from architecture and business to art and politics—runs deep into the heart of each city. Indeed, it’s impossible to imagine what these cities would have looked like today, without the vast contributions of their Armenian residents.

In the 19th century, the unofficial capitals of Armenian life, culture, and production were Bolis in Western Armenia and Tiflis (today’s Tbilisi) in Eastern Armenia—two cities with tumultuous, complicated histories which, today, are mere shadows of their once-vibrant Armenian pasts.

Last year, I spent three days in Bolis before heading on an excursion to the lost villages and towns of Western Armenia. What started as a millennial Eat, Pray, Love journey ended up turning my understanding of individual and communal resistance, resilience, and survival on its head. Physically, I was on Turkish soil for only two weeks but mentally, I am still there—learning and questioning.

After haranguing my family all year about my trip to our ancestral homeland, they express interest in visiting the other capital of years past—a city that was almost exclusively Armenian two centuries ago, but where today, one has to really dig to excavate any Armenian remnants. And so, we set out for the road trip of a lifetime.

On the road

With rolling green hills and lush trees that sparkle against the sun, the pristine scenery of Armenia’s northern countryside is absolutely breathtaking. Approaching the checkpoint at Bagratashen, we get out of the car and make our way to security. Of Armenia’s four borders, only two are open for its citizens—and just one for those with American passports. A man with a name tag in Georgian script awkwardly catches me glancing at his chest, trying to make out the delicate swirls that mean something I probably can’t pronounce. He still lets me through.

Bustling metropolis

Arriving in the Georgian capital, we are welcomed by a bustling melting pot of different cultures, languages, religions, architectural styles, and street vibes. People of all colors and backgrounds roam the busy center streets and pavements are lined with cars from all of Georgia’s neighboring countries. One can’t help but wonder if this is what Armenia would have looked like today, if half of its borders weren’t closed.

Where east meets west

In this city, one can stop for a quick, no-frills lunch at a Turkish kebab shop, grab dessert at the Dunkin’ Donuts next door, then cross the street to shop at an Azerbaijani-owned shoe store, which lies next to a century-old apartment building with mainly Armenian tenants. Or you can skip it all for a long afternoon at a fancy two-floor McDonald’s.

Local livin’

The apartment we’re staying at is just outside of the city center; many Armenians live in the building, we’re told. As we pull up to the front, we elicit the glances of a few local men playing backgammon. Like their counterparts in Yerevan, they size up their foreign guests and smile without breaking eye contact. Before we could get a word in, our host, Julia, runs out to embrace us. She is the sister of a longtime employee at my uncle’s grocery store in Yerevan—so, basically family.

Our Tiflis

Walking into our home for the next day and a half, we pass through this ramshackle door—deceptively hefty and sturdy. We soon learn that Julia was born and raised in Tiflis, but her grandfather came from Mush (in Western Armenia) in 1914 to escape the genocide. “And we just never left,” she chuckles. Like many descendants of survivors who sought refuge in the diaspora, Julia possesses a deep love and pride for her family’s new home. Perhaps it’s this reason or because she is our host and unofficial tour guide, that Julia rarely mentions Tiflis without the possessive “our” in front of it.

Finding Tumanyan

We begin our journey to the Tiflis of yesteryear with our favorite Armenian writer. There is no greater personification of the beauty of Armenian prose than the stories of Hovhannes Tumanyan, the Armenian people’s national poet. He lived in Tiflis for 14 years, where he created some of his most well-known classics. Though much has been lost in this city, Tiflis still retains a distinctly Armenian voice through Tumanyan’s home, which was recently converted to a house museum. Had we come just a few months earlier, we would have missed this gem.

'A' is for Armenian

Language is perhaps the first thing to pop into your mind when asked about what makes Armenians so special, yet it is also the easiest—and ironically, most quiet—way to hide one’s Armenianness. In Turkey, stones with Armenian writing cover homes and barns and abandoned churches like fossils, with most villagers not knowing the true origins and meaning of these ancient lines. In Tiflis, we enter Tumanyan’s world through a grand door, which depicts the letter “a” in Armenian.

Language lives on

From tourists to taxi drivers, the Armenian language—usually the first thing to go in an assimilated diaspora—remarkably lives on in Tiflis. Nearly every corner we turned, Armenian was in the air. Though few physical institutions and landmarks allude to an Armenian presence in this city, there is no greater proof of it than hearing our language, spoken and lived. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that the only major Armenian relic honored in Tiflis is the house museum of the Armenian people’s most beloved writer.

Havlabar

In the evening, we venture to the historic Armenian neighborhood of Havlabar (renamed “Avlabari”). It may be hard to imagine now, but in the 19th century, this was the place to be. Located within the largely preserved windy passages of the Old Town, today’s Havlabar is anything but preserved, resembling nothing of its once-majestic past. Once home to most of the city’s 150,000 Armenians, today, few of its Armenian dwellers remain.

Resilience in the street

Following years of religious destruction, Havlabar has fallen victim to another crime. In the past decade, mass urbanization and gentrification have forced the departure of many of the district’s remaining Armenians. Walking through these streets at night, one doesn’t get the impression that so many prominent Armenians once called this flashy, bright-lit neighborhood "home." Yet, in between the chic cafes and trendy metros, one might stumble upon an old house or two, magically unscathed and forgotten. And, just like in Turkey, the weight of history will cloud your eyes.

Resilience in the village

While venturing in Western Armenia last year, we came across an area that was long known for its old Armenian homes. When the Turkish government tore them down just three years ago—on the centennial of the genocide—to replace them with gaudy, poorly-built apartment buildings, they missed one. Walking around the ghost town, we came across this humble structure—the sole-remaining Armenian home in this once-vibrant part of Mush, which overlooks the mountain where fedayi, Kevork Chavush, was once buried. Today, in Tiflis, I wondered: maybe this is the home Julia’s grandfather left behind over a century ago.

Etchmiadzin in Tiflis

Until WWII, Tiflis boasted over two dozen Armenian churches. About half were destroyed during the Stalinist purges and the rest either abandoned or later repurposed into Georgian Orthodox churches. Only two functioning Armenian churches remain today, one of them—the 18th-century Etchmiadzin Church—is in Havlabar. We visited Etchmiadzin, but the doors were closed. In front of the church lies a khachkar (cross-stone), dedicated to victims of the April 9 Tragedy, when 21 demonstrators lost their lives in an anti-Soviet protest in 1989.

St. George

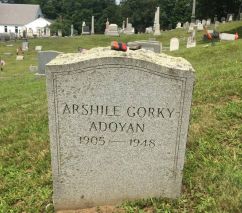

Leaving Havlabar, we make our way to the St. George Armenian Church, the other functioning Armenian church in Tiflis. We’re told that, within its walls, we’ll find the Armenian Pantheon, where many prominent Armenian artists and intellectuals are buried. Alas, we were mistaken—but not disappointed. In the courtyard, we encountered dozens of tombstones of famous magnates, sculptors, and singers. And though we could not find them, among the buried are the ashugh, Sayat Nova, and his wife.

Armenian life in Tiflis

By the gates, there is a board with bilingual (Georgian and Armenian) postings of Armenian news and events throughout the city, including an upcoming puppet show at the Tumanyan house museum. It is obvious that St. George is the cultural and spiritual center for Tiflis Armenians. Inside, the kind caretaker informs us of the true location of the Armenian Pantheon, and we’re off again.

Finding the Pantheon

Once a vast complex dating back over 300 years, the St. Astvatsatsin (Mary) Church that belonged to it was destroyed in the 1930s and, just a decade and a half ago, the remaining cemetery was bulldozed to build the Georgian cathedral down the road, which is one of the world’s largest religious buildings today. Of the few tombstones that remain here, we came across Tumanyan’s. Just hours before, we wandered the halls of his beautiful home. It felt unfitting that a man of such prowess and inspiration would end up in this quiet, hidden place.

Underneath the gold dome…

As we exit the Pantheon, my uncle points to the Holy Trinity Cathedral of Tbilisi. We stare in silence at her grandiosity—literally built on the bones of Armenians—taunting us and the hundreds of souls laid to rest in this tiny, forgotten cemetery. Once more, we confront the brutality of cultural erasure and appropriation. In Turkey, they are mosques; here, they are churches.

Mother tongue

Before leaving, Julia invites us to her apartment for coffee and pastries. It’s tight quarters; things have been difficult since her husband’s passing. My uncle asks why she hasn’t moved to Armenia yet. With her signature grin, she responds, “I could never leave our Tiflis.” Between sips of dark grounds, I tell her that I am envious of her command of our language. She smiles, “yes, I have a Georgian accent, but I’ve always prided myself in speaking our mother tongue.”

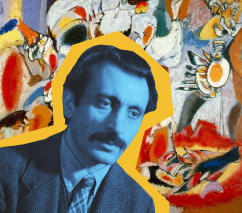

Sojourn for sujuk

Mom remembers that she wants some sweet sujuk, or as it’s called here, churchkhela, before heading out on the road. Julia walks us to her local market, bustling on this warm Sunday afternoon. As we retrace the steps of those who came before us, we feel the spirit of Tumanyan, the poet of the people; Sayat Nova, the bard of the Caucasus; Aram Khachaturian, the colorful composer in a time of black and white; and the countless others who felt inspired here. It’s no surprise why, or how, this city touched them all.

Renaissance

As we munch on our treats in the car, Julia’s words linger in the air. “Norits hametsek” (“Come again soon”). Our gracious host—like the taxi drivers and tourists, tour guides and artists we came across—are, once more, creating an Armenian renaissance in this unique, storied city. It’s a different form of resistance, resilience, and survival—and it could not be sweeter.

The street of saints

According to legend, Vardan Mamikonian’s daughter, Saint Shushanik, was once buried somewhere along this street, which is one of the oldest in Tiflis.

Inside the Armenian Pantheon

A quadrilingual listing of all of the people who were buried at this site. The sheer quantity is overwhelming.

(Photos: Lilly Torosyan)

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!