Zulal: The floating triangle

September 08, 2018

From performances at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and the MET’s upcoming exhibition on Armenia, to concerts in churches, museums, and universities, it seems as though the Zulal a cappella trio is really after only one thing: to immortalize the essence of Armenian folk songs. But they are not mere archivists or preservationists. On the contrary, their joy in breathing new life into ancient tunes and narratives, the sweet nuances of their voices, the graceful choreography of their movements, all come together to reveal a cornucopia of songs that defy age and language. They feed the soul with intricate rhythms celebrating love and our relationship with nature, evoking an appreciation for the beauty of a simpler and slower life. How do they do this? My in-depth interview with the trio, conducted on the morning of their last concert in Beirut, reveals the secrets behind their meticulously refined performances and the wealth of their shared perspectives.

Zulal's “Notes to a Crane” carried me on its wings for years. The album played on repeat until I was able to experience them live in the summer of 2017 in a concert that cast such a spell on Beirut audiences that the trio was back in Lebanon for two more concerts the following year hosted by the Hamazkayin Armenian Cultural and Educational Society.

There is something elusive and enigmatic about folk songs: One moment they evoke time-honored self-perceptions of national identity and cross-regional dynamics, the next they offer an alluring mixture of music and words that can instantly touch any heart.

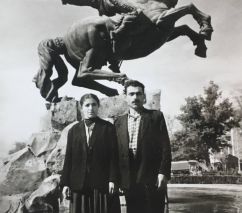

A Zulal concert is a journey to the source and back. The trio seamlessly and effortlessly pulls the audience out of time, out of the age of Facebook and social media, to take them on a horse-and-carriage ride through idyllic rural settings and glimpses of bustling village life. They spin stories of lovers looking for a place to hide, of spring winds flowering gardens, of melting snows inspiring a boy to go after his sweetheart, of young women teasing the men at the village market…

Suddenly, all becomes familiar.

Each generation reinvents the past to make it relevant. To make centuries-old folk songs fit in today’s world without destroying their essence is quite challenging. Fifteen years ago, Zulal was one of the first groups to venture into the sacred source of Armenian folk music and try to make it "new." It was even more remarkable, since the trio emerged not from Armenia or the Middle East, but from New York and New Jersey—far from the homeland. And through their different backgrounds, they are able to carve out an extraordinary musical experience for audiences young and old.

It's an early Sunday morning in April. I am driving to a blossoming hill overlooking the Mediterranean, where the three members of Zulal are staying on their latest trip to Beirut. The anticipation of meeting them in person and addressing the various queries I have jotted down while playing their albums until the wee hours of the previous night keeps growing as I take the turns to reach my destination. "Will they lend their voices they so preciously need for tonight’s concert and detail their journey?" I ask myself on my drive.

“I am Yeraz,” she says, leading me to the dining room where Teni and Anaïs greet me with cradling smiles. The breakfast table laden with avocados, eggs, apples, cheese, and chorizo, the enthusiastic response to the nature of the questions, and the animated conversation that follows all seem to rise straight from a folk song delivered in trio.

In the end, they call it their "dream interview." Read it below in its entirety and become part of the inspiring world of Zulal.

A crystal tone resonates when Yeraz Markarian reflects on the trio's relationship: "We remind each other to eat, drink water and sleep; we care for each other. We can say: I don’t like how that note sounds, can we change it? And we can say: I trust you, I respect you as a musician, as a human, I know you’re bringing this from the best possible place, I am not going to take personal offense at that comment—it just gets in our way." (Photo: Kathi Littwin, 2015)

A crystal tone resonates when Yeraz Markarian reflects on the trio's relationship: "We remind each other to eat, drink water and sleep; we care for each other. We can say: I don’t like how that note sounds, can we change it? And we can say: I trust you, I respect you as a musician, as a human, I know you’re bringing this from the best possible place, I am not going to take personal offense at that comment—it just gets in our way." (Photo: Kathi Littwin, 2015)

Loucig Guloyan-Srabian: Tell me about Zulal's beginnings. What brought you all together?

Yeraz Markarian: We were acquaintances. Anaïs was performing a cappella as part of a festival. Hearing her sing for the first time, I was moved by her voice. I sang a cappella in college. Teni also sings a cappella, and our love for a cappella is what brought us together. We realized that there are no small a cappella groups that sing in Armenian.

At our first rehearsal, we didn’t define our purpose too clearly—we didn’t have the intention to perform. Our goal was to explore within ourselves what it would feel like to sing a cappella in Armenian. Later, we agreed to concentrate on Armenian folk music because of its special qualities.

L.G.S.: Instruments like the dhol and duduk have characterized Armenian folk songs. What's different about

Yeraz Markarian on the merging of cultural influences:

Yeraz Markarian on the merging of cultural influences:"We try to get inside the song. In the beginning we called it finding the key to the song. I don’t know if it is the key to the song, the soul of the song or the soul of the person who wrote it. Then we think of the times. We ask: What was it like to be a young girl who wanted to be asked to be married? We realize that it wasn’t like a 25-year-old, but a 12-year-old." (Photo: Mher Vahakn, 2018)

a cappella renditions?

Teni Apelian: A cappella as a form already has its own universe. Traditional Armenian music was sung not in harmony. Taking this approach to Armenian folk music defines it through a different form.

Anaïs Alexandra Tekerian: It’s fun because we have the freedom to arrange all the music as a trio. Singing a cappella is harder than singing to an instrument because we all start with a note and then the tuning is between us. To stay in one place and to keep the rhythm, we must act as instruments as well. That musical challenge in a cappella appeals to us.

L.G.S.: Though you perform these songs in your own unique way, they sound very natural, almost like they are being presented as originally intended. How have you developed this attitude to approach the music as interpreters and not archivists?

Y.M.: It comes from who we are. We don’t live in a village in Armenia; we live in the modern world. We drive cars to drop our children off at school; we listen to all kinds of music; we went to various universities in North America... We’re just inspired by our education, our upbringing, our whole lives. I wonder how we could be preservationists. We each bring different musical backgrounds into the arranging whether it is the song Jojan—which has jazzy harmonies—or Janiman— which has major classical elements inspired by the New York Philharmonic’s New World Initiative.

T.A.: It’s by default, a product of the lands that we’ve shared: Our repertoire spans regions across modern and historical Armenia. We're also members of the diaspora and have also been influenced by a number of artists, songbooks, and so forth. As a result, we have a diverse and wide listening palette. Whatever comes through our arrangements is naturally filtered through our eyes and sensibilities. If we were singing arrangements of pieces that were created for us in Armenia, it would be different. But because so much of what we do is the arrangement, then that attitude as interpreters and not archivists— as you were saying—is natural to who we are.

If it comes from you, it will be real and genuine. And I think that’s understood by audiences.

Yeraz Markarian

L.G.S.: You come from different musical backgrounds. How do they merge?

T.A.: It’s hard to parse that out. The pieces are in our own heads and hearts musically, but then also, every piece asks for something different, so we’re always trying to listen first to what the melody calls for. There is less of a deliberate choice in terms of the influences and more of our response to the melody.

Check out photos, videos, and audio recordings from the Zulal trio below and share your impressions with us. For more songs, transliterations, and translations visit Zulal's website.

A.A.T.: I mostly listen to classical music and world music, so in my arrangements, there will be elements of that automatically. The harmonies and the melodies that are in our heads come out. But we cannot know exactly how much of our musical backgrounds is in the songs. In the future, when people look at our music and analyze it, I don’t know whether they will be able to parse it.

L.G.S.: What about the creative process and the standards that you follow, the sources you use, the expertise needed to bring a song to life? You seem to follow a discipline, which ensures that nothing is lost in translation.

T.A.: Step one is to pay attenti

Anaïs Alexandra Tekerian on the creative process:

Anaïs Alexandra Tekerian on the creative process:"There is no band leader in Zulal. All three of us are band leaders, but we’re just collaborators. It’s a very different dynamic to have one person in charge of a group or to be in an equilateral triangle." (Photo: Mher Vahakn, 2018)

on to the lyrics and to the region from which they come. There is a lot of energy spent up front, so that we not only intellectually understand what we’re hearing, but also pay tribute to it musically. In the beginning, we were less rigid about that. But as we developed, this became more of a standard procedure.

Y.M.: Step one (b) is that we have to like the song...

T.A.: We tend to have similar tastes. It’s a balance that we try to strike with every arrangement to take it somewhere new. At the same time, we’re very much touched by the essence of the song in its original form. If we look at world music, and specifically to Armenian folk music that’s being defined today by many artists, the songs that are successful do just that.

A.A.T.: We sit at a piano or in a circle and start improvising before we touch the piano, to see how the harmonies come to the song. Some songs are easier to harmonize to and others have more of a code to break into it. Then as a trio, we usually find a skeleton of a part and go to the piano to find each part. We all end up doing each part together.

T.A.: It’s a very collaborative process. Everything happens in three: We do the arranging in three. There was a time when everyone did their own part and we're at a point right now where we...

Y.M.: ...We're all up in each other’s business!

L.G.S.: How do you assess the state of Armenian folk music and the new renditions of songs? Can we consider Armenian folk songs as an open source? How much liberty can one take in presenting and reinterpreting them? Should there be a limit?

T.A.: Those are difficult questions to answer. I think [Armenian folk songs are] an open source and there should be no limit. We’re thrilled at what has happened since allowing ourselves to tap into Armenian folk music as a source of inspiration for new music. It’s one of the hottest things coming out of Armenia and in the diaspora right now. I feel like we figured it out that this is a bountiful source of creation.

Y.M.: It’s a real treasure. It’s not that stuff my grandmother used to sing. We’re able to tap into this music and feel that it’s not old and dusty and archaic. Many bands are breathing new life into it in Armenia, where they were so close yet so far from it emotionally. It’s beautiful to have the archivists as preservationists—we need them because they maintain a balance; we need to remember these songs as they were sung, and to be able to uphold that is a beautiful thing. That’s our source, and it doesn’t exist just so we can feed out of it, but it exists so that we live with it in our modern world.

T.A.: One word of caution is that if you’re going to create a new interpretation, it’s important to make sure that you’re not using one of the current interpretations as your source. We have seen that a lot. As appealing as the new is, if you’re looking to recreate something, do make the effort to go back to the source and make something different, instead of doing a reinterpretation of the reinterpretation.

A.A.T.: However, there is something poetic about it and in line with the idea that folk traditions transform through time, when people, for example, take a Zulal arrangement of a piece and assume that a course we have stuck in there is part of the song, and that version becomes part of the song.

When I hear a new musician from a different culture that I am not familiar with, it’s a way for me to travel to that culture and to feel a part of it in that moment; somehow it makes me feel that I have taken something—a part of world culture—from there.

Anaïs Alexandra Tekerian

L.G.S.: How do you think folk music can bring about changes in the way we perceive our identity? How much can music be part of identity?

A.A.T: Good question. Who can live without music? There are people who cannot react to music, but that is only a fraction of the population. Art is necessary to live. I asked a doctor friend, who works with terminally ill people, "How do you survive being confronted by death?" She said: "Everyday I go either to a concert, a theatre, or a gallery. I have to feed my soul with art in order to survive." That was very beautiful. Music is one of the most accessible arts. Everyone listens to music. It’s one of the things that makes us human.

L.G.S.: When you put something that is part of your identity in a universal context, do you see it from a different perspective? How does that reflect on you?

Y.M.: I love this question because we do se

Teni Apelian on sharing part of your identity in a universal context:

Teni Apelian on sharing part of your identity in a universal context:"Anytime you share a part of yourself, whether it’s musical or other, it only strengthens that part of you. As does the exchange of our appreciation for our culture." (Photo: Lusi Sargsyan, Erit.am, Komitas Chamber Hall, Armenia, 2016)

e ourselves through someone else’s eyes. We’ve performed in front of entirely non-Armenian audiences. I remember feeling the attentiveness and the respect of the audience in Germany. In Lisbon, women who did not understand a word of what we were saying were crying. They came up to us and said: "We cannot believe how beautiful this music was, we felt you as people, we felt your emotions, we felt the meanings of the songs, it spoke to us!" What we bring to the melodies is a part of it, but it wasn’t us, it was the folk music through us that touched them; the melodies and the songs themselves are very powerful. In Brooklyn an American guy was so moved that he was crying—հոնքուռ‑հոնքուռ ("honkur-honkur," to bawl or cry uncontrollably)—tears rolling down his eyes when we were singing "Manchus"("My Boy"), a song by Armen Movsisyan and the only current folk song we sing. It’s about telling your child: "That’s where our home is, that’s where the grass is no longer green, that’s where there is a crack in the wall, that’s where our home is my son. Let’s go there!"

Seeing ourselves, and seeing this music through other’s eyes is a reflection back on us. It gives us… not strength, but…

T.A.: … Perspective, self-definition. It proves that music does have the ability to transcend language and to connect to a culture without understanding precisely what is being said. It’s two-fold. What we do recognize is the ability to express some elemental things that perhaps are not particularly Armenian, but that are evoked through those melodies and those ideas.

L.G.S.: Why do you think your songs appeal to diverse audiences? How does a someone in say New York connect with a song from or about Van, a place he or she has perhaps never seen or even knows much about?

Y.M.: Because they do! The themes in folk music are universal: love, loss, work, shopping for food, not wanting to work, trying to put a child to sleep, dance, joy, weddings—these are all part of humanity. How can we not relate to them?

T.A.: Also, the music and arrangements tap into the heart of these themes, and the combination appeals. We honor the original melody, but we also try to create something new that’s pleasing at least to us, and we’re happy that it translates.

L.G.S.: Where does Armenian folk music fit in world music? Can you draw parallels with other cultures in terms of themes, intonation, appeal, and so on? What makes it special?

Y.M.: Some of the time signatures such as the quarter tones, the key structures, and the musical note structures set Armenian music apart from some cultures and from people who have not been exposed to those elements in world music. When we were performing as part of the World Music Festival in Germany, we met musicians who had not been exposed to these unique rhythms and note structures. We were teaching them "Tamzara" (a dance song from Palu), which is a dance song in 9/8 [time signature] and they were struggling to catch on with the rhythm. To some extent, that sets [Armenian folk songs] apart and makes them interesting, enticing and intriguing for other audiences to hear. Most people in the world have not heard 5/8, 11/8, and 9/8 [signatures] and that’s why, say Bulgarian music has such a powerful presence for people who hear it for the first time. The music in its core just touches people and they are blown away.

T.A.: In terms of style, we can compare it to Bulgarian music or to the music of the Caucasus. You do have to acknowledge the similarities regionally, but Armenian music has its own tradition, even though there have been direct musical and linguistic exchanges with Turkish and Kurdish neighbors in regions like Palu.

Y.M.: Look at "Sari Galin" ("Mountain Girl"), which these [Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish] cultures claim as their song. It's sung in different languages. It belongs to everybody. It all has to do with that handh

Teni Apelian on the growing popularity of folk music:

Teni Apelian on the growing popularity of folk music:"As the world gets increasingly busy, noisy and digital, and there is so much to digest, pass through and organize, somehow this music, that is so simple in its essence, becomes more and more appealing to us all, because we feel a need for simplicity when everything around us is exponentially becoming faster." Photo: Mher Vahakn, 2018

olding and cultural overlap.

L.G.S.: The way you perform and share the joy of what you have discovered reveals how much you love every bit of what you do. However, is there a song that you particularly enjoy performing?

Y:.M. I don’t know if we have the same answers, I would be curious to know...

A.T.T.: Every song has its charm.

T.A.: I really like singing "Dal Dala" ("Branch to Branch")...

A.T.T.: Yes, "Dal Dala."

T.A.: There are certain songs that just feel delicious to sing, that have moments where we naturally interact with each other. We all like "Dal Dala."

Y.M.: I really like that one, but I have two answers. Usually, the most recent arrangement is the most exciting one. Like the song "Laz Bar" ("Laz Dance") in 5/8 [time signature] that we will debut tonight. It’s from Palu—it’s one of my favorite arrangements.

T.A.: People wonder what’s it all about—it’s about goats and մածուն ("matzun," yogurt in Armenian). We have combined two versions of the same song, which is kind of a theme. Well, not too much of a theme, but we like making connections across time and across regions in historic Armenia.

L.G.S.: Armenian folk music is quite popular among Armenians these days. I'm curious about other cultures. Is folk music growing in popularity? Is it a shared experience?

A.T.T.: There is a huge overhaul of Armenian music, but also, there are certain cultures in Eastern Europe and non-European cultures, like in Africa and South America, that have always had a strong folk traditions and have always been working more with folk music. In North America, people listen to certain political bands or country music as a form of folk music. In Western Europe, they have children’s folk repertoires. I do think there is extra energy right now, though; everyone can just turn on their iPhone and become a musician. There is some interesting stuff coming out.

The Carnegie Hall and the 92nd Street events were at the heart of what we strived to do: to take the music that we adore culturally and open it up to a global audience through world music programming.

Teni Apelian

.jpeg/Carnegie%20Musical%20Explorers_preview(1)__320x320.jpeg) Anaïs Alexandra Tekerian on children's reaction to the Carnegie Hall's Musical Explorers program:

Anaïs Alexandra Tekerian on children's reaction to the Carnegie Hall's Musical Explorers program:"Children are open and passionate. They really are the best audiences. One of the news stations made a video clip of the program and interviewed a couple of kids. There was this little Latino kid talking about the concert and how much she loved it, and she said: You know because I speak Creole and Armenian. She fully identified with that because she now knows 3 words in Armenian and 3 words in Creole. When you experience music and you’re touched by it, you feel part of it." (Photo: Carnegie Hall-Musical Explorers)

L.G.S.: Tell us about your educational projects. One of Zulal's signature events is bringing Armenian folk music to thousands of elementary school children in New York. How did this come about?

T.A.: Carnegie Hall’s Musical Explorers considered Zulal as part of their Musical Introduction Series. We’ve always had a component of music education for children in what we do. We’ve created something that appeals specifically to children and we've gone to schools and presented it. We took that on a whole other level, in conjunction with the curriculum that was created specifically for children by Musical Explorers. They were able to come to this music from their educational point of view and choose what they felt would resonate with the kids. They chose "Doné Yar" ("Dear Love"), "Tamzara," and "Ha Nina" (a folk song from Sasun) for the first series. For the second series, they chose "Sari Sirun Yar" ("Mountain Beauty"), "Lachin u Manan" ("Lachin and Her Spinning Wheel"), and "Hink Edz Ounem" ("I Have Five Goats"). We did the first series in conjunction with calypso and hip-hop. The idea of the program was to put three very different genres on stage together and to consider not only the individual genres but also the connections.

Y.M.: When we performed at Central Park for the New York Philharmonic, some of the children from Carnegie Hall’s Musical Explorers came and one of our friends said, "These children were dancing 'Tamzara' when you guys were singing…"

T.A.: She said that she went up to them and asked: "հա՞յ էք ("Hai ek?"). Are you Armenian?" And they said no.

Y.M.: So, they knew the "Tamzara"; they were singing along, they were dancing it in New York, in the middle of Central Park, at an orchestral concert. They had learned something and felt it was part of them.

A.T.T.: Children who have been exposed to different types of music are musically more adapt and will, in general, be more appreciative of music in the future. Children who have heard different time signatures and different types of tonalities early on can catch on to those sophisticated melodies much earlier.

L.G.S.: You've released three albums over the past 15 years. How do you decide that it’s time to release a new album?

T.A.: Releasing an album 15 years ago was a different thing than it is now. We’re just spoiled—we pace ourselves and our fans are an integral part of what we do. We do spend a lot of time crafting and carefully putting things together to create an album. Our next album will come out much quicker than the third did.

Y.M.: We’re comfortable with our pace and take a lot of care. There is a lot of meaning in each album. "Seven Springs" took a long time for many reasons: The title, the words, and the message were very planned and thought out—the album is called "Seven Springs", there are 14 songs on the album. We still print albums. There is something really gratifying about holding something in your hand, absorbing the artists’ message, communicating with the artists and feeling their energy while you’re listening to their music. But that isn’t necessary for all. I personally find that very gratifying to be connected to the materials that the artists themselves have designed or collaborated to create. Kevork Mourad has been graciously doing the art for our albums. It’s beautiful to be able to look at that, to hold it and experience it while you’re listening.

"There’s a bittersweet mood throughout,"John Schaefer of Soundcheck, WNYC said about Zulal's 2007 sophomore album. (Album art: Kevork Mourad, 2007)

"There’s a bittersweet mood throughout,"John Schaefer of Soundcheck, WNYC said about Zulal's 2007 sophomore album. (Album art: Kevork Mourad, 2007)

"Seven Springs," released in 2015 is "an ode to the spring equinox celebrated in pagan Armenia," according to the trio. (Album art: Kevork Mourad, 2016)

"Seven Springs," released in 2015 is "an ode to the spring equinox celebrated in pagan Armenia," according to the trio. (Album art: Kevork Mourad, 2016)

"Passionate, playful, and deeply emotional," said award-winning filmmaker Atom Egoyan about the trio's first album, released in 2004. (Album art: Kevork Mourad, 2004)

"Passionate, playful, and deeply emotional," said award-winning filmmaker Atom Egoyan about the trio's first album, released in 2004. (Album art: Kevork Mourad, 2004)

L.G.S.: Any new discoveries? New ventures?

Y.M.: For the first time, we will be singing Vaché Sharafyan’s composition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s Kevork Mourad’s project and it’s going to be part of the Metropolitan’s exhibition on Armenia. That’s going to be very exciting. We don’t know the song yet; it’s being created.

We’re focusing on getting our songs into print. We constantly get emails from choirs all over the world who ask for our arrangements of Armenian songs. Almost every song has been asked for, so we’re printing a songbook of all the songs that we have ever sung and arranged up to today, including the fourth album. As we’ve said, we’re not archivists, but the melodies will be recorded, and our arrangements of what people are enjoying and asking for will be available. We’re excited about it!

L.G.S.: Do you collaborate with a music publisher?

T.A.: We’re self-produced, which allows us to do things ourselves. We’ve never felt pressured that we’re not keeping up. We want to make sure what we put out is true to our hearts, and not…

Y.M.: …not a marketing message. We do our own social media; we do our own bookings for gigs. Each one of us will take one show and run with it; we even do our own web design—Teni does it!

T.M.: That allows us to be unmarred by noise from the outside. It’s less stressful and more pleasant.

L.G.S.: There definitely is a bond among you. How does it work? Armenians are notorious in failing to work in groups. Fifteen years is such a long time for a music group to be together. What’s the secret of your survival?

Y.M.: [Laughs]

Yeraz Markarian on the secret of Zulal's survival:

Yeraz Markarian on the secret of Zulal's survival:"It’s about being real, honest, genuine and vulnerable, knowing that any form of change is coming from a place of love." (Photo: Mher Vahakn, 2018)

T.M.: I think of us as a floating triangle: If one side weighs more than the others, the thing will drop. The secret is acceptance. After so much time together, we know each other well; we know each other’s quirks and idiosyncrasies. If you just accept the people you adore in their full glory—strengths and weaknesses—then you no longer have any internal struggles; you can work together and move forward.

A.T.T.: It’s just because artistically, we’ve not had major arguments. Just the occasional, “I don’t like that, can you fix it?” We fundamentally agree, which is lovely. We have had ups and downs, we have had moments of strife, but we’ve become so close that we’re like sisters. Even if we have moments of disagreement, there is this deep love for each other that is underneath, and it’s supporting us.

Also, we've developed over time; we've created this Zulal that started taking a life of its own before we really had any idea that would happen. In the olden days, artists were inspired by divinity, and this floating triangle is our own version of that. We’ve got this project that we started, and we must keep afloat. It’s not a difficult task or obligation because there is that love and common purpose between us.

T.A.: When you realize that your innate ability to do this relies on your fellow "Zulals" being as good as you, that you’re only going to be as good as the three of you are. It’s no longer a singular thing; it’s not about one of us—it’s about the three of us. In a cappella, you’re vulnerable: If everyone is not locked in, centered, and equal, then something goes off-balance. Whether its the tone, the pitch... Once you really internalize it, you realize that it’s not about protecting yourself or bringing one person forward—it’s about the collective and that’s a very freeing discovery...

Y.M: … [a discovery] that we wish for all Armenians.

[Teni and Anaïs voice their agreement, as if they are repeating a line in the chorus in one of their songs]

You need to be heavily rooted to the source, otherwise the tree will fall. You need to understand it at depth, respect it, honor it and make it your own. Then you can fly, you can reach the stars. Every one of you!

Yeraz Markarian

L.G.S.: What piece of advice would you give to aspiring young musicians who dabble with folk music?

Y.M.: Keep dabbling! Don’t stop!

A.T.T.: Do go to the source, because there is a lot of wealth there. Stay there a bit—explore and understand it, and don’t be afraid. You need to know the fundamentals of the craft. Once you have gone to the source, then you can go with whatever you want, you can go crazy, but make sure you study the basics.

T.A.: Also, like with all art, to be able to go off something if it doesn’t do what you want it to do. If you don’t feel that you have really accomplished what speaks to your heart, it's important to learn to let go, because otherwise, you're creating a lot of noise.

Video

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!