The dying art of letter writing

January 23, 2020

In this age of go-go-go, time is our biggest commodity and our most precious resource. Yet, for every “upgrade” our high-tech gadgets provide in immediacy, we lose that much in intimacy. What was once the go-to mode for communication, letter writing has been lost to an ever-changing world. But is it really “replaceable?” And why should we even care at all? Experience the author’s journey of uncovering an old family letter, and discover why this neglected art form deserves a զարթօնք (zartonk | renaissance).

What are the most precious things you own?

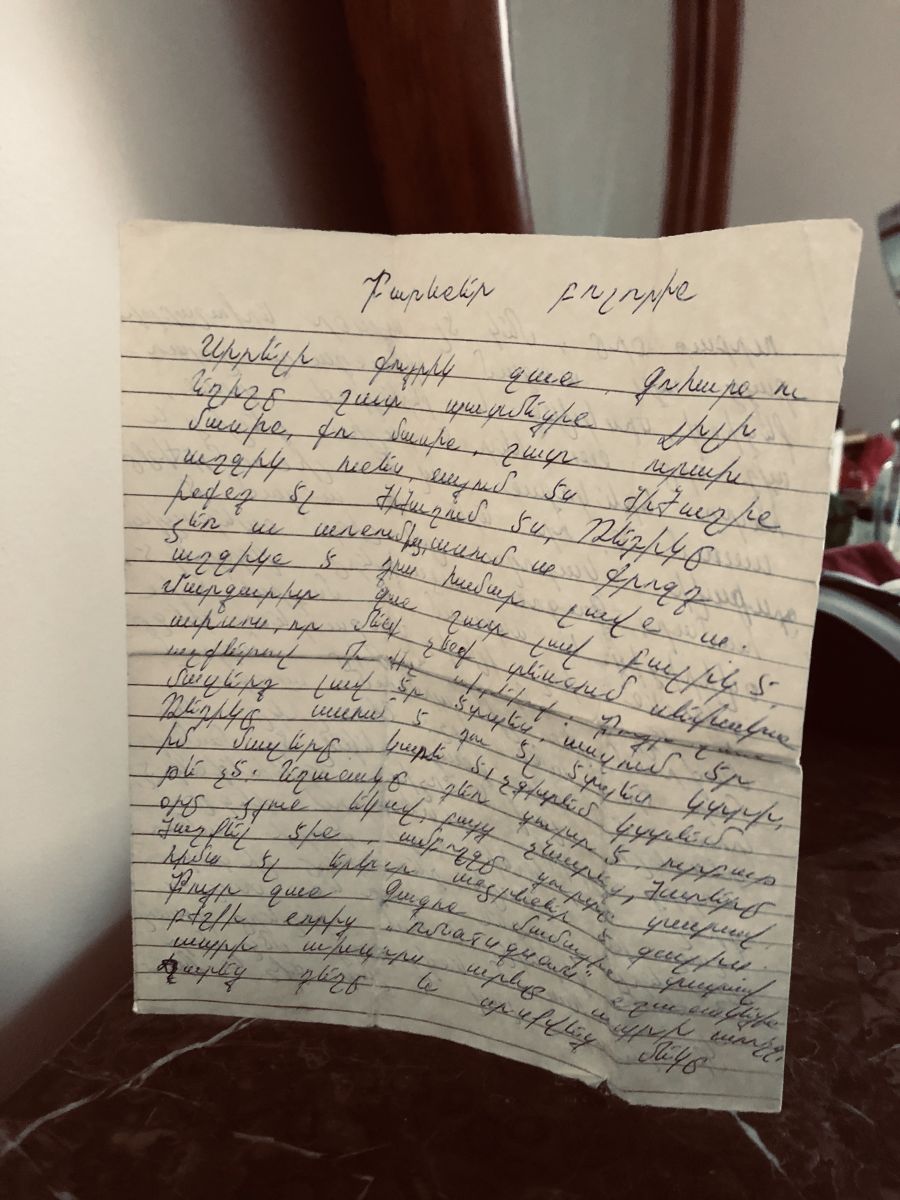

“Hellos to everyone:” A snapshot of Aunt Seda’s letter on mom’s dresser. (Photo courtesy of Lilly Torosyan)

“Hellos to everyone:” A snapshot of Aunt Seda’s letter on mom’s dresser. (Photo courtesy of Lilly Torosyan)Is it those diamond earrings you received at your Sweet Sixteen, or the four-wheeler that you spent three summers after school saving up for? Perhaps it’s the hunk of wires and keys, similar to the one I am typing on as we speak? No, of course not. The most precious items in our possession are not the ones with the most retail value.

Wars have been fought over the most seemingly meager things—like that ugly tea set that your mom adores or the ասեղնագործ (aseghnagortz | needle-lace) made by your great-grandmother, a genocide survivor. These are the real jewels that we scramble to hold on to, especially in increasingly hyper-materialistic times. They tell a story; it’s up to us to read between the lines.

Yesterday morning, while searching for a pair of tweezers in my mom’s room, I checked all of the usual spots before coming across something unusual, quietly tucked away in a neat corner of her dresser: a quarter-century-old handwritten letter (in Armenian) by my aunt from newly-independent Yerevan to her little sister, a new bride living in the little diasporic haven of Watertown, Mass. I didn’t have to read it to know that this was special. Over the years, mom moved residences four times, each time, doing a “purge” of unnecessary, trivial things—the things we can live without—and each time, this little piece of paper quietly moved with her.

Dated April 26, 1993, Armenia had recently emancipated from the Soviet Union, only to find itself immediately embroiled in a war with neighboring Azerbaijan. This was the period many today refer to as the “cold, dark years,” when electricity was limited and masses lined up for bread rations. In her letter, my aunt conveys joy at receiving a generous three hours of electricity in the morning and three at night. She then mentions my grandmother’s illness; here, too, she expresses hope and optimism. Though the war “froze,” with a ceasefire the following year, my grandmother passed away soon after. It is amazing how much can be conveyed (and not conveyed) by one tiny sheet of paper.

Soul paper

We often think of letter-writing as a romantic product of a bygone era, one befitting a period drama, with two angsty star-crossed lovers sending notes across a vast ocean, long before its floor was lined with telecommunication cables. But before we get wistful, we acknowledge that letter-writing carries real limitations: for one, it cannot portray the little crow’s feet perched on to the sides of your loved one’s eyes as they read your words; nor can it amplify the slight crack in their voice as they say, “I miss you,” upon reaching the end of your letter. Tonality, subtlety, and instantaneous reactions are all but eviscerated. Ultimately, we are all better off moving on from this antiquated and inefficient system, right?

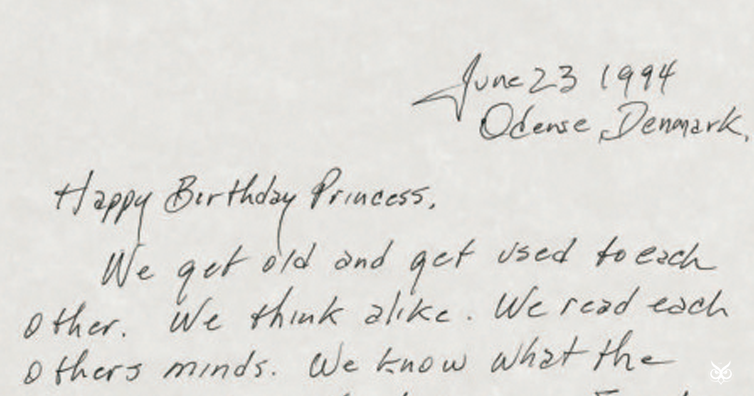

"Once in a while, like today, I meditate on it and realize how lucky I am to share my life with the greatest woman I ever met," Cash wrote in a birthday letter to June while he was in Odense, Denmark. "You're the object of my desire, the #1 Earthly reason for my existence." Read the entire letter here.

"Once in a while, like today, I meditate on it and realize how lucky I am to share my life with the greatest woman I ever met," Cash wrote in a birthday letter to June while he was in Odense, Denmark. "You're the object of my desire, the #1 Earthly reason for my existence." Read the entire letter here.

Indeed, researchers say that body language accounts for 55 percent of our communication, 38 percent is the tone of voice, and the rest of what we are trying to say, just seven percent, are the words themselves. On paper (please excuse the pun), it looks like we may be better off ditching this prehistoric system—like 93 percent better.

But I suggest we think about words in a different way.

Reading between the lines

Writing a letter is much like composing a poem—one plans out what to say, writing and rewriting with a kind of diligence that many today would consider cumbersome, often taking days, weeks—perhaps even months—to compose the perfect set of words to capture the range of sentiments to be conveyed on one precious piece of paper. The images portrayed would be the only ones imprinted on the reader’s mind until the next letter, which could have taken months to arrive. It is a craft that requires patience, diligence, a bit of skill, and lots of emotion; in short, it is a work of art.

It is also the purest form of speaking from the heart. One cannot fall back on (or hide behind) the distractions and deceptions of appearances, sounds, and gestures. When we subdue our senses, our words become louder, more intentional, and, by default, more personal. Why is it that we can hardly recall the last text message we received but we remember and cherish every letter or note? There are few mediums so powerful as the handwritten form.

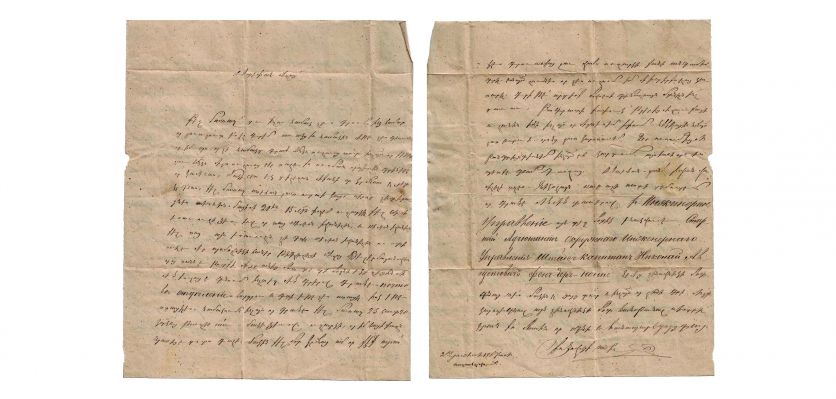

Lest we forget that, until very recently, this old tool was the form of communication. During (and immediately after) the Cold War, telephone service was unreliable and far too expensive, so millions relied on letters to stay in touch with their loved ones, caught on the other side of the Iron Curtain. 1993 was less than a lifetime ago.

Why resurrect a dying art form?

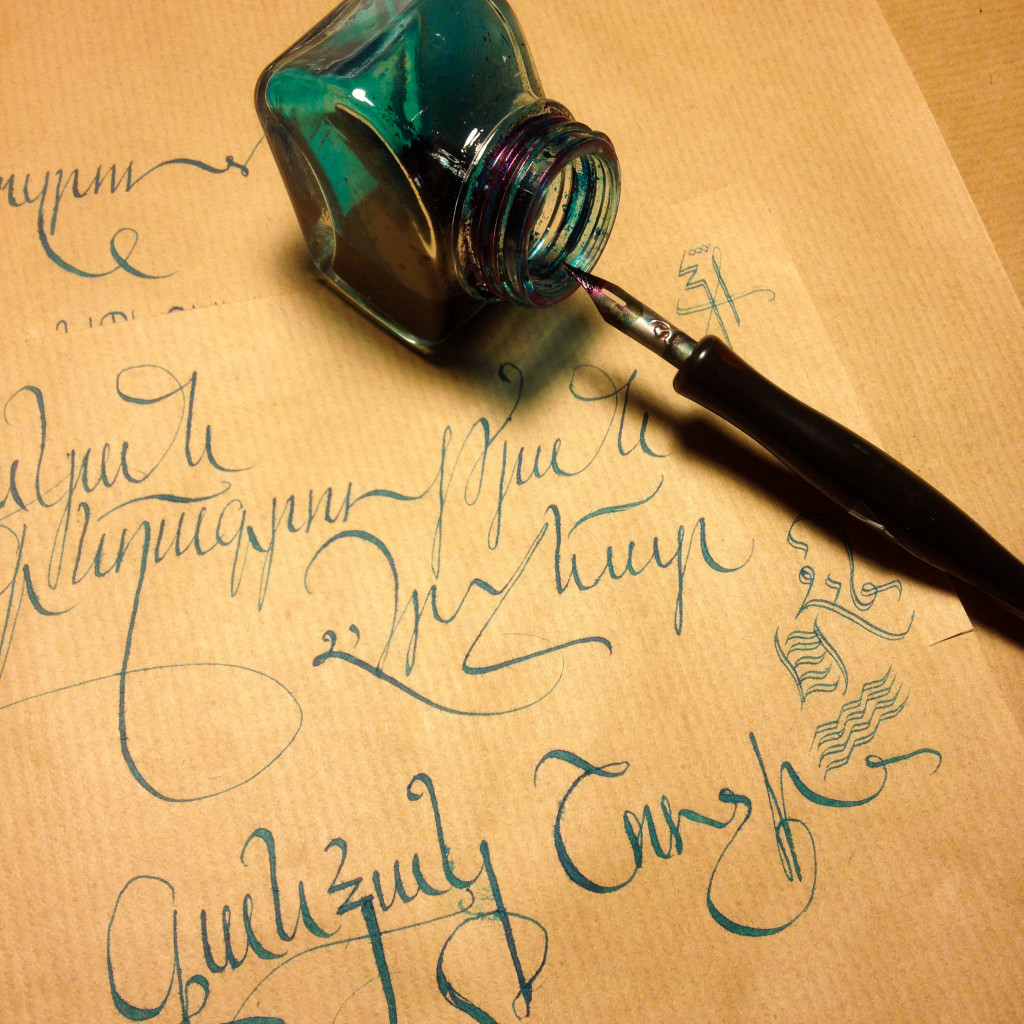

In 2018, I interviewed Ruben Malayan, who specializes in the ancient art of Armenian calligraphy. He described the beauty of the Armenian script and how composing each long, elegant stroke is almost a meditative process for him and a way to connect with our ancestors. Like calligraphy, khatchkar (ancient cross-stone) carving, and needlework, letter writing is a vessel through which Armenians have created timeless works of art for centuries, yet all are in need of revival. As Armenians, we pride ourselves on remaining steadfast to our millennia-old traditions, but we must ask: do we lose a piece of our culture—and our humanity—when we discard (or neglect) these old traditions?

An example of Malayan's calligraphy (Photo: media-arts.space)

An example of Malayan's calligraphy (Photo: media-arts.space)

Though this looks like a negative prognosis, the good news is that we can reverse these trends. Unlike calligraphy, khatchkar-carving, and needlework, which require substantial resources and apprenticeship, letter writing is not reserved for the most talented and apt of writers. All one has to do is pick up a pen and speak through paper.

My aunt’s language is simple; her transitions are, at times, abrupt; and her words spill over to take up a single line on the next page—the way it does when you miscalculate the amount of space you need to write your message on a greeting card. I’ve come to learn her unique shorthand, like the way she writes her “N”s and how her “A”s, “P”s, and “T”s swirl together to look like one long letter. It is personal in a way that no series of Word or iOS fonts could ever be. Other than my mom, I am likely the only other person who has seen and touched her letter. Yet, had I come across it just five years ago, I would have thrown it by the wayside, since my ability to read Armenian was so poor. Reading it now, I feel a connection to the women in my life that I did not share before.

We think it’s hye time to bring back this old art form, don’t you?

Exercise opportunity: Your turn to write!

Think of the old family letters collecting dust in your attic (or in your mom’s dresser). Imagine the joy you received when you read those for the first time. (Heck, imagine the joy you feel when you receive a letter in the mail!)

This year, instead of a text message or Facebook wall post, try sending a letter to a loved one for their birthday. Do you know Armenian? Brush off on your skills, using resources like Nayiri to help guide you. Interested in learning Armenian but don’t know how to begin? Check out our list for ways to get started on your journey.

Of course, you can write your letters in whatever language you please, but we’re here to provide you with the tools, should you choose to take a crack at it in the mother tongue! And later, if you want to share your family stories, thoughts, or discoveries with the world, send it our way—we’d love to publish it. Together, we can do our part in reviving one of the most precious art forms in human history, all while discovering more about ourselves and the collective ties that run through our veins.

Check out a TEDx talk on the lost art of letter writing by Elspeth Penny and an interview on the history of the handwritten letter with author Simon Garfield in our video section below!

Also read these love letters by Hrand Asadour and Zabel Donelian (Sibyl), compiled and translated by Jennifer Manoukian.

Video

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!