Easter in retrospect: The 7 stories you missed in Armenian illuminated manuscripts

April 08, 2021

Has it not occurred to you that the Last Supper conjures up one specific Da Vinci image in Western culture? That a medieval Armenian counterpart may look quirky in an endearing way? Here we have put together a selection of Armenian miniature depictions of The Passion of the Christ. You may be surprised to find out how their fate has been intertwined with the glorious and tragic fortunes of our nation!

Arshile Gorky, a forerunner of American abstract-expressionism, venerated the thirteenth century Armenian miniaturist Toros Roslin, who has often been viewed as a precursor of Giotto for his portrayals of the human condition.

Van, where Gorky was born, and Cilicia, where Roslin served at the courts of Armenian kings and princes, were vibrant centers of manuscript production in historic Armenia.

From the tenth century onwards, Armenian miniaturists left behind a trail of extraordinary artistic achievements. They perfected the art of composition, and explored an infinite range of color harmonies and proportional relationships. Making and owning an illuminated manuscript was such an honor, that both artists and owners added their names to the colophons.

While a diversity of traditions and styles were practiced in the medieval scriptoriums of the Armenian world, the schematic portrayal of biblical scenes, as well as the relationship between characters were passed down faithfully from one generation to the next.

The artistic imagination of Armenian miniaturists continues to fascinate us even today. Many of their works are recognized as universal masterpieces. Two years ago, a number of inspirational examples were showcased at the MET exhibition dedicated to the artistic legacy of Armenia.

About thirty thousand Armenian manuscripts have survived continuous invasions throughout the centuries. When fallen into foreign hands, they were referred to as “captives.” There are tales of monks who carried stacks of these sacred books to safety, and of deportees who risked their lives to salvage what they could.

They have always been among the most vulnerable items of our cultural heritage. Lately, during the 2020 Artsakh war, precious manuscripts were transferred from the Gandzasar Monastery to the Matenadaran in Armenia. Only a decade ago, the Armenian church sued the prestigious J. Paul Getty Museum for the return of eight illuminated pages from the Zeytun Gospels.

Scattered all over the world, from world class museums to provincial libraries, exquisite pages of illuminated manuscripts span the history of Armenian Christian art. Despite being desecrated, looted, destroyed, cut out and sold for centuries, they have become highly charged symbols of the creative Armenian spirit, and the survival of a nation caught in the crossfire of warring empires.

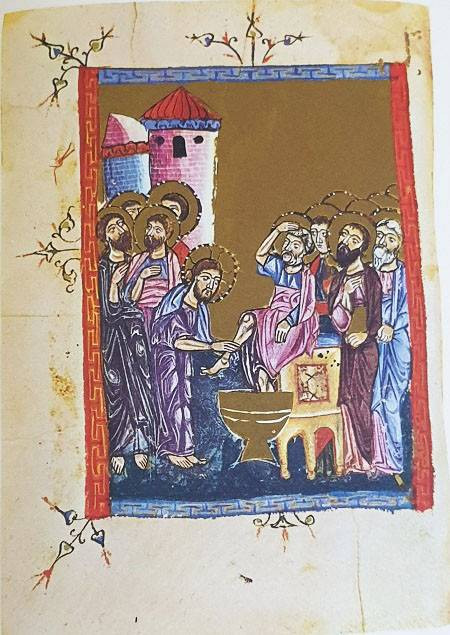

Washing of the feet

Jesus kneels before Peter, holding one foot in his hands. Exalted by his humility and love, Peter points at his head as if to say: Not just my feet! Wash my head too. Peter is sitting on a high throne. Three apostles are depicted behind him. Others are present through their halos. Four apostles stand behind Jesus, against the backdrop of two towers. Unless their sins are washed away, they have no place in the kingdom of God. The graphic purity of the painting is accentuated by the synergy of colors and forms, the almond-shaped eyes, and arched brows.

Interesting fact: "O great master of mine, Yesayi, remember this unworthy disciple of yours Toros." The colophon mentions the abbot of the Monastery of Gladzor in Syunik. The art of illuminating manuscripts was practiced in the scriptorium of the Gladzor University.

(Miniature painting: "The Washing of the Feet," by Toros of Taron, Gospel of Gladzor, 1307, Mechitarists’ Library, San Lazaro, Venice).

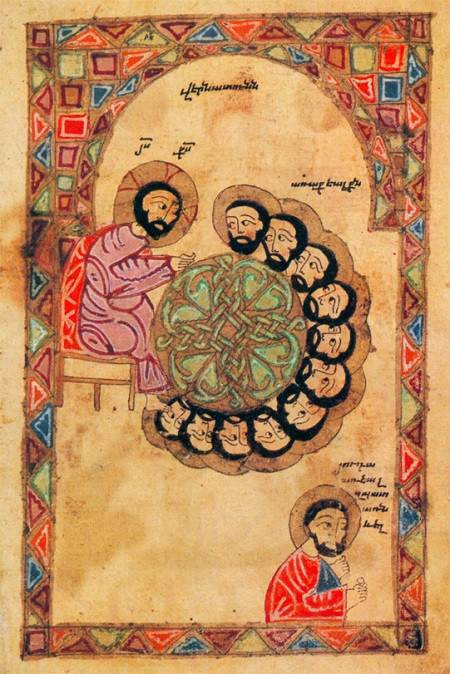

Last supper

This miniature from the Artsakh Gospel is unique in a quirky way! While in medieval art Jesus and his disciples eat on a scarlet tablecloth laden with bread, fish, and wine—symbolic allusions to his imminent sacrifice, here in the representation of the meal believed to be the first communion, the table itself is a precursor of the Eucharist. When Judas leaves and is about to betray (at the bottom), twelve remain at the round table: Christ and the apostles, like 12 months at the “annual wheel,” where linear time turns back towards the end of time.

Interesting fact: The Artsakh school of miniature painting flourished between the 12th and 14th centuries in more than 30 venues and monastic centers like Gandzasar, Dadivank, Amaras, Targmanchats Vank, and Gtichavank. It was influenced by the artistic traditions of Syunik and Ani, as well as local trends and folk art.

(Miniature painting: Artsakh Gospels, 14th century, Matenadaran collection).

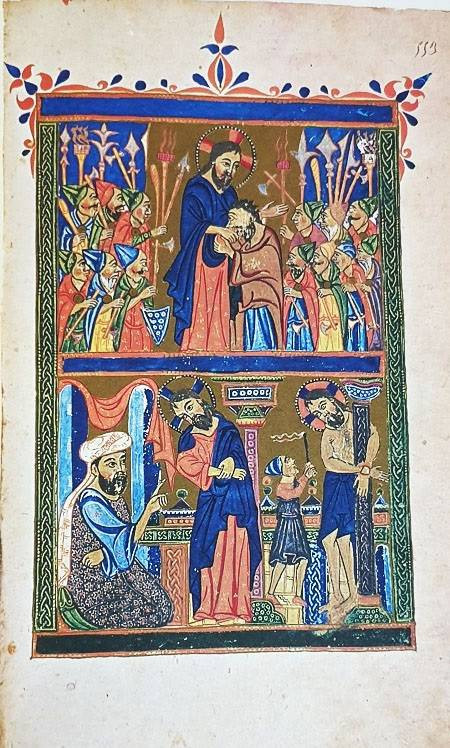

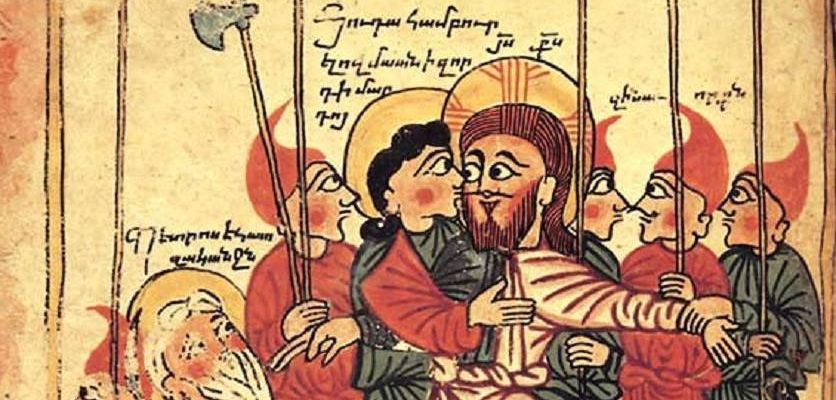

Betrayal

One of the few miniature paintings by the 15th century priest Mkrtich Naghash is divided into two parts. In the first part, Judas leads a band of soldiers to the Garden of Gethsemane, and kisses Jesus, in a deal with the chief priests to identify and arrest him. Jesus is dressed in royal robes against a gold background, surrounded by the temple guards armed with spears, swords, clubs, and torches. In the second part, Jesus is brought to trial in Sanhedrin’s court, where he is mocked and condemned to death. The dynamic realism of the image, the ethical approach to the theme, as well as the rich color palette mixed with gold, give the images a majestic feel.

Interesting fact: Mkrtich Naghash, the Archbishop of Tigranakert, was sent to exile by the Ottoman authorities, because he had built a church steeple that towered over the surrounding mosques. He became the poet of the exiled. Yet, he is remembered as Naghash, meaning “painter.”

(Miniature painting: "The Betrayal by Judas," by Mkrtich Naghash, The Bible of Naghash, 1418-1422, Khlat, Bitlis, Mechitarists’ Library, San Lazaro, Venice).

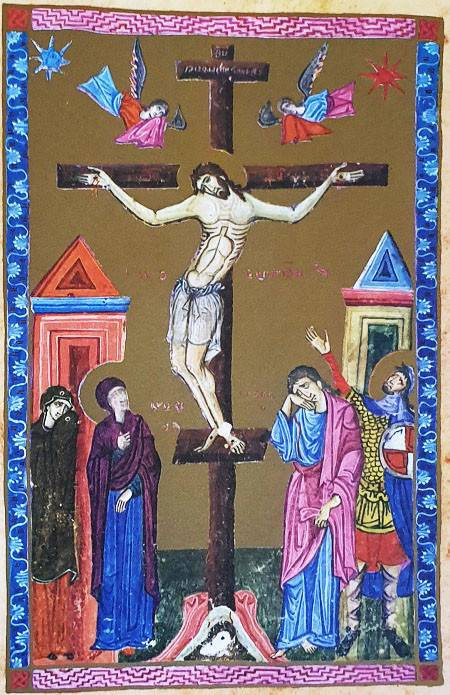

Crucifixion

Christ stands, rather than hangs on the cross. He is powerful even in death. Mother of God and Mary Magdalene stand at his feet. John is the only apostle to witness Jesus' crucifixion. Behind him, the Roman centurion sees first-hand the death of Jesus, looking up and pointing at him. The sun and the full moon—the first after the vernal equinox, appear on the two sides of the cross. Angels hover around Jesus in grief. Gold hues are used sparingly to create harmonies between blues, purples, reds, and whites. The painting overwhelms in its pious benediction, depth of grief, yet expressive serenity. Both simple and sublime, it attests to the refined taste of the artist, and is considered a masterpiece.

Interesting fact: The miniature is part of the Gospel of Skevra, which was taken as loot by the Mamluks from the Lampron Fortress in 1375, and auctioned off. It was bought by Euphemia Hetumian, heiress to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia.

(Miniature painting: "The Crucifixion of Jesus Christ," by Constantine of Skevra, 1193, Mechitarists’ Library, San Lazaro, Venice).

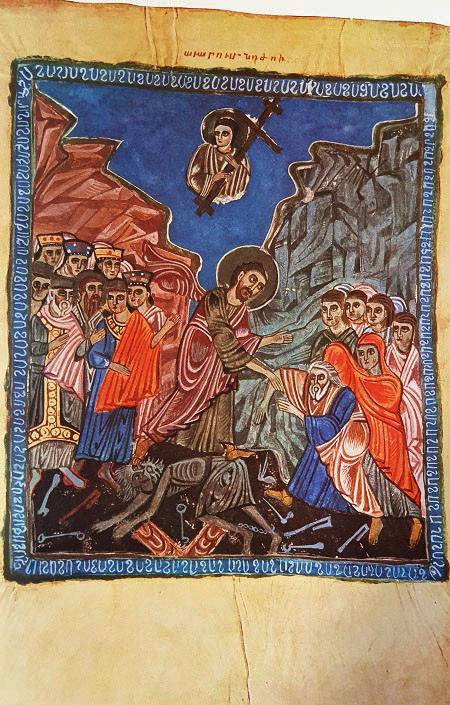

Descent into hell

After his death and before his resurrection, Jesus breaks the gates of the underworld. He stands triumphantly over an old man in chains who personifies Hell. Nails and locks are strewn all around. A haloed angel holds an eight-winged cross between two hills against a dark blue sky. Jesus gestures towards Adam, with Eve and Old Testament people behind him. A group of kings, with David and Solomon at the front, are depicted on the left. All wear crowns, except John the Baptist. Their deep-set eyes and the brown shadows on their cheeks express emotional intensity, as well as dramatic suspense. The moment symbolizes the triumph over darkness, evil, and death.

Interesting fact: Stylistic and compositional similarities with early medieval frescoes in Cappadocia are stark proof of the openness to cultural exchange between Byzantine and Armenian art centers.

(Miniature painting: Attributed to Grigor Tsaghkogh, the Translators' Gospel, 1232, Matenadaran collection).

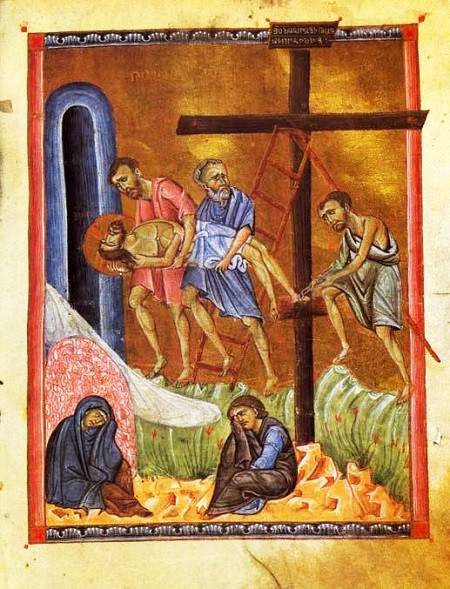

Entombment

Joseph of Arimathea takes Jesus down from the cross to bury him with the help of fellow followers. A white shroud is spread over the grass, at the entrance of the tomb carved in the rock. Mary, mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdalane are clad in purple and brown—the colors of mourning. Grief prevails at dusk, while Christ’s body is being carried to his tomb. Inner tension builds in refined colors and delicate lines—the grass ripples, and the fluid folds in the clothes intensify the moment.

Interesting fact: The painter, Toros Roslin, was a pioneer of emotional expression and psychological perception. Commissioned by the kings, princes, and religious leaders of Armenian Cilicia, he worked at the scriptorium of the Hromkla Fortress, and left behind more than two hundred miniature paintings.

(Miniature painting: "The Descent from the Cross," by Toros Roslin, Malatia Gospels, 1268, Matenadaran collection).

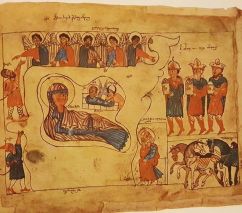

Resurrection

This laconic watercolor depiction of Christ’s resurrection is a rare masterpiece of early medieval Armenian miniature art. Christ’s tomb is shaped like a sarcophagus. An angel invites the holy women’s attention to the empty tomb and the burial cloth left behind, while the other points at Jesus in regal red and blue, crowned with a cross-inscribed halo. There is movement all around, while the guards are sleeping on their shields. The narrow foreheads and almond-shaped eyes are reminiscent of those depicted on the frescoes of the Church of the Holy Cross on Akhtamar Island. Strictly schematic and graphic, yet deeply moving and spiritual in essence, the image possesses a quality that is both bright and transparent.

Interesting fact: The exact provenance of the painting is unknown. It belongs to the only surviving illuminated gospel from a set of documented manuscripts in Karin before 1915. Tragically, the rest were either destroyed by the Turkish authorities or used as wrapping paper in local markets.

(Miniature painting: "The Resurrection of the Lord, Holy Women at the Tomb," by Evagris the priest, Gospel of 1038, Matenadaran collection).

Sources:

- Դուռնովօ Լ․ Ա․ , Հայկական մանրանկարչութիւն, Երեւան, 1969։

- Դրամբեան Իրինա, «Թորոս Ռոսլին․կեանքն ու արուեստը»․ http://hpj.asj-oa.am/5639/1/13._I._Drambyan.pdf

- Ճանաշեան Մեսրոպ . Հայկական մանրանկարչութիւն, Հ․ 2, Վենետիկ, 2001։

- Ղազարեան Վիգէն, «Մանրանկարչութիւն», Քրիստոնեայ Հայաստան Հանրագիտարան. https://hycatholic.ru/

- Mathews Thomas F., & Taylor Alice(2001)․ The Armenian Gospels of Gladzor: The Life of Christ Illuminated. Getty Publications Virtual Library. from http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/0892366273.html

- Չուգասզեան Լեւոն, ««Խաչելութեան» թեման Թորոս Ռոսլինի Արուեստում», Հանդէս Ամսօրեայ, Վիեննա, 1988, Յունուար-Դեկտեմբեր, էջ 191-218։

- Չուգասզեան Լ․, «Էջքը Դժոխք» մանրանկարը Թարգմանչաց Աւետարանում», Երեւանի պետական համալսարան. http://www.ysu.am/files/16L_Chugaszyan.pdf

- Տէր Ներսէսեան Սիրարփի, Հայկական մանրանկարչութիւն, Հ․ 1, Վենետիկ, 1966։

- Rand Harry (1991). Arshile Gorky: The Implications of Symbols. University of California Press.

- Քոլանջեան Ս․, «Մեր ձեռագրական կորուստները»․ http://echmiadzin.asj-oa.am/5266/1/27.pdf

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!