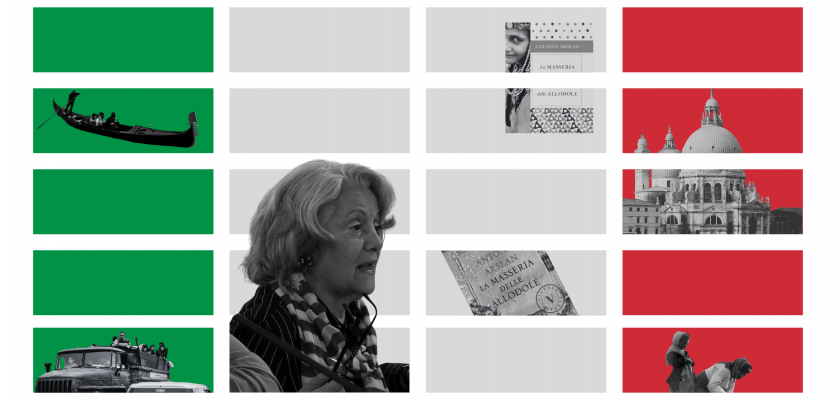

Interview | Antonia Arslan: From The Lark Farm to Nakhichevan, from Kharpert to Stepanakert

May 04, 2025

They say the Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul—Bolis to Armenians—connects West and East, Europe and Asia. But for Antonia Arslan, the true bridge between the Orient and Europe is not a structure, but a people: the Armenians.

Most readers know Antonia Arslan as the author of The Lark Farm, a bestselling novel that tells the story of the Armenian Genocide. Adapted into a film by the Taviani brothers in 2007, the novel brought Arslan international acclaim. Last year marked the 20th anniversary of its publication. Translated into 20 languages and now in its 45th edition, The Lark Farm remains a defining work. But Arslan’s contributions go far beyond literature.

I sat down with the retired Professor of Modern and Contemporary Italian Literature at the University of Padua to discuss her writing, poetry, activism, the challenges facing Armenia, the Diaspora, and much more.

Antonia Arslan grew up in Padua, a city in northern Italy not far from Venice. Though raised in a predominantly Italian environment, she had early and profound exposure to the Armenian world.

“I’d say I’ve been connected to Armenians and Armenianness since childhood. My Armenian grandfather—a renowned surgeon and a deeply authoritative figure—was a constant presence in our home. It was he who, when I was nine, told me the story behind The Lark Farm—the story of how his brother, Smpad, was decapitated... and everything else. So I had a clear sense of Armenianness, though it remained a private experience in many ways. We lived in a city with only a handful of Armenian families—three or four in total. And with World War II raging during my childhood, maintaining a sense of community was difficult. The language and culture around me were entirely Italian, yet I was always captivated by my Armenian heritage. It made me different from the other children—there was always something else, something deeper, to talk about. But it was only once I came to understand that we Armenians are a bridge between West and East that my Armenianness could emerge fully and freely.”

Antonia Arslan’s Armenian identity truly began to blossom through a deeply symbolic act of cultural bridging: translating the poems of Western Armenian poet Daniel Varoujan, one of the victims of the Armenian Genocide, into Italian.

“Since the Great Awakening, the Zartonk, at the start of the nineteenth century, Armenians have always sought to translate from Western languages. For me, translating Varoujan’s poetry marked the beginning of my own awakening to my roots. I first discovered a French translation of his The Song of the Bread, but it was quite liberal. I then read English translations, which were much more faithful to the original.

"It felt like a bell ringing—an alarm that awakened my Armenianness. Reading those poems was like reclaiming another identity, like rediscovering a lost homeland. It helped me understand what historical Armenia meant to my ancestors—the lands they came from."

“Varoujan portrayed rural life with remarkable simplicity and poetic force. Being especially sensitive to poetry—and having memorized countless French, Italian, English, and German verses—his work touched me deeply. That’s how, quite unexpectedly, I began translating him. At the time, I was lecturing in modern and contemporary Italian literature at the university, but I put everything else aside. There was only one obstacle: I didn’t know Armenian—I was never taught. So I sought help. I worked with two collaborators: a young Iranian-Armenian man with a remarkable gift for translation, and a young woman who had studied Armenian in Venice. Together, we translated the poems line by line. I asked them to read each poem aloud to me so I could hear its music—something Varoujan clearly considered as he wrote. The result was praised by the professor of Armenian at Venice, who said the translations were perfect. To date, the collection has reached its eighth edition. Imagine that—eight editions of an Italian translation of a poet virtually unknown in Italy!”

Varoujan’s poetry resonated with Arslan because of her family history, too.

“Technically, Varoujan studied in Venice—he studied right after my grandfather. I don’t know if they ever met. He studied Italian and learned the Italian poetic forms. The interesting thing—at least as far as I’m concerned!—is that he used the form of the Italian sonnet in the first poems of The Song of the Bread, which he truly mastered, before turning to more Oriental forms. At the same time, his attention to the life of peasants marks a strong difference between his own work and Italian poetry. We can absolutely draw an analogy with the best contemporary Western poetry. Varoujan wrote in a minority language, less widely known than others, but his intellectual and creative power placed him on par with the greatest poets of the late 19th century. In essence, Varoujan was a symbolist.”

Antonia Arslan wrote her first novel at 66, not a typical age for a writer to rise to fame.

“Earlier on, my only creative outlet had been poetry, though I never published it. While translating Varoujan, I also began writing some ballads, which I called Anatolian—or Armenian—ballads. Eventually, I published a few of them in a book titled La Bellezza Sia con Te (May Beauty Be with You) in 2018.

"The idea to write a novel came when I began thinking seriously about telling the story my grandfather had once told me."

Antonia Arslan had a special connection with her Armenian grandfather, her one and only guide to the Armenian world. This is not a coincidence – Grandfather Yervant saved little Antonia’s life.

“I was nine. I was gravely ill with a recurring fever—it kept returning, and I was close to death. My grandfather, being an exceptional doctor, had the idea to treat me with penicillin injections. It worked. He saved my life. After that, he said I needed to spend more time with him—he believed my Italian grandfather and my father were spoiling me. So, he took me away on a one-month holiday.

“During that month, he told me the story—his family’s story. He had been born in Kharpert but left at the age of thirteen. He spoke of his childhood there, of his plans to return home one day to see his brothers. He had a brother named Smpad, and many half-brothers from his father’s second marriage—eight or nine in total. All of this stayed buried quietly inside me, like a secret, until it finally began to surface through Varoujan, and all the work I did on that project. Of course, by then I was no longer young. But these things emerge when the time is right.”

The decision to write a book on Genocide as a first novel is a risky move in many ways.

“The story had to be told. It came about by itself. You have to understand one thing: it re-emerged from within, the story of my grandfather, the way he kept it to himself for so many years. He never talked about it. He brought his children up in a totally Italian way.”

In fact, neither Antonia’s father, a leading specialist in otorhinolaryngology who discovered the cure for several diseases, nor her uncle, a notable art critic, was fluent in Armenian.

“My grandfather had two children. My uncle was born in 1899 and was called Yetvart, but everyone called him Vart. He had no idea they were calling him – a sturdy man – Rose! I myself found out later. Grandfather called my father, who was born in 1904, Kayel, like his own father. When his sons were born, he gave them Armenian names, Yetvart and Kayel. Ten years later, the Genocide happened. Only later on did he take out the final -ian from the surname, in 1922.

“But the Armenian given names were only used within the family. In the outside world, my father was known as Michele, and uncle Vart was known as Edoardo, and neither of them learned Armenian, except for a couple phrases – my father would say ‘parev’ and ‘inchbes es’, and that’s it. Their Italianization was their father’s way to protect them from the fear of the Genocide.

In spite of this, Antonia’s family remained part of the Armenian Catholic community and attended mass in San Lazzaro regularly: for Christmas on 6th January, every year on Easter Sunday, sometimes for the Blessing of the Grapes on 15th August. However, grandfather Yervant did not share much of the tragic history of their family with his own children, even though Antonia’s father did know how his uncle died.

"It was I with whom my grandfather talked. He had trust in me because he saved my life, and also because he had little left to live – he died a few months later. He felt like he had to tell this story to someone; perhaps he hoped I would tell this story to the world sooner or later."

For Arslan, Armenianness is not only a matter of her family's past or bitter memories of the Genocide. Her Armenian identity is vibrant and vivid, it is something that she lives every day. A great part of this journey is her adamant activism – she has been relentlessly raising awareness about the Armenian Genocide, Armenia’s current security challenges, the ethnic cleansing of Artsakh and the cultural genocide of Nakhichevan, educating Italians and others on the past and current wrongdoing against the Armenians as well as on Armenian culture in general. She prides herself on the fact that Italy recognised the Armenian Genocide twice.

"Italy recognised the Genocide twice, not once. Everyone cites the recognition of 2019, but Italy had already recognised it in 2001, among the first countries in the world. In 2001, it was recognised (nearly) unanimously – I think only one MP abstained, as the petition, in his opinion, wasn’t tough enough towards Turkey. In Italy, by now, no one questions the fact that the Armenian Genocide was perpetrated."

After all, the cultural connections between Armenians and Italy are deep and long-established.

“The first printed book using Armenian characters was published in Venice in 1512. Not in Constantinople—in Venice. Armenian ties to Venice date back as far as the year 1000, when the Doge first mentioned the Armenians. These connections reached their peak in 1717, when the Doge gifted an island to Abbot Mekhitar. That was more than three hundred years ago. Since then, Venice has become one of the great centers of Armenian culture, especially in the 19th century. People often say that the Jews are a universal people—but the Armenians, too, were absolutely universal.”

But the recognition of the Genocide is unfortunately still far from universal. The fact that recognition motions were passed in Germany and the United States is a great achievement, but it is highly unlikely that the same will happen in Turkey any time soon.

“They will never do it. I’ve always hoped that they would, but how can they tell their people after more than 109 years, ‘We told you a ton of lies’? Admitting that would be an immense source of public embarrassment. That, I think, is the crux of the matter. On top of that, Turkey would be faced with the need to pay reparations, and lawsuits concerning property and ownership rights would inevitably arise. At this point, the focus for the Armenians should be on achieving recognition from as many nations as possible.”

The situation becomes even more dire when we turn to the recognition of Armenia’s present-day security challenges and the crimes committed against the Armenian population of Artsakh. The ethnic cleansing of Artsakh and the cultural genocide of Armenian heritage in Nakhichevan, perpetrated by Azerbaijan, have largely gone unnoticed in Italy. This is partly due to Italy’s strong economic and political ties with the Aliyev regime. Despite this, Antonia Arslan continues to fight tirelessly for the Armenian cause. Together with Professor Aldo Ferrari from the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, she recently edited the volume Un Genocidio Culturale dei Nostri Giorni (A Cultural Genocide of Our Days), which examines the systematic erasure of Armenian cultural heritage in Nakhichevan.

“Through Nakhichevan, we’ve known what will, sadly, happen in Artsakh. That region no longer contains a single stone that recalls its Armenian past. Even the foundations of the churches were dug up and erased, leaving no traces of where the churches once stood—nothing visible, not even from an aerial view. And this was one of the most ancient centers of Armenian civilization.”

In this context, Arslan urges the Diaspora to ‘get denser’ and intensify its efforts to raise awareness about Armenia’s current security challenges.

“The Diaspora must draw the attention of EU decision-makers to the fact that Azerbaijan has a ‘Western Azerbaijan’ agenda within its Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Alongside this, they’re pushing a narrative that seeks to erase Armenian Christian heritage by branding it as ‘Caucasian Albanian.’ This amounts to falsifying historical facts and spreading disinformation. In Italy, people are aware of these lies, and fortunately, most of my audiences are Italian.”

Unfortunately, contemporary Azerbaijani ethnic identity is often shaped by a deep-seated hostility toward Armenian history and culture.

"It’s an imposed identity. Young people, even those as young as fifteen or twenty, have been indoctrinated. I recently read a book by an Azerbaijani female writer, now based in Italy, in which she described Baku thirty years ago. At that time, the city was home to coexisting cultures and civilizations, including an Armenian presence. In her own family, her Azerbaijani aunt was married to an Armenian man.

"Of course, there have always been differences between the peoples, but Armenians did live there. The current hatred is artificially manufactured to distract from 1) the lack of democracy, 2) the absence of independent political parties, and 3) the suppression of free expression, which even silences figures like the renowned Azerbaijani writer Akram Aylisli. His book, in which he speaks of the Armenians, was published with my support. It’s a quick and poignant read – you can finish it in an afternoon. The book tells the story of his childhood in his hometown of Aylis, which inspired his pen name, and where Armenians and Azerbaijanis once lived side by side.

For simply having written that short book, they demonized him, confined him to his home, stripped him of his pension, and now, at over 85 years old, he is unable to leave his house."

Together with the Armenian world, Antonia Arslan lived through the painful and difficult days following the fall of Artsakh and the tragic ethnic cleansing of its Armenian population.

“I’ve been to Artsakh several times, and I’ve always had a deep affection for it—the people, the land. I love everything about Artsakh. My heart is broken, torn apart by the exodus. Everyone fled. Everyone was forced out. That’s undeniable. In Artsakh, there are places like Dadivank and Gandzasar, which are truly remarkable. For me, Dadivank is one of those places where I had some of my most profound spiritual experiences. Now, it’s all lost. Along with the memories of my grandfather’s city, Kharpert, I also carry the memories of Stepanakert in my heart.”

Years ago, Arslan’s love for Artsakh led her to establish a school there. The school offered a range of educational opportunities, from preschool to secondary and professional studies, including practical skills such as carpentry and sewing. At its peak, the school had more than 600 students. Whether the school will reopen in Armenia remains uncertain.

When I asked Antonia Arslan what Armenia means to her, she responded:

“It’s the second country of my heart—paese del cuore—alongside Italy. I only know how to write in Italian, and I will never deny that. But as many literary critics have noted, my writing carries an oriental, international influence. Armenia holds a special place in my heart. In fact, I always say I’m 100 percent Italian and 100 percent Armenian, much like Aznavour was with his Frenchness—not half and half.”

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!