Minas Lourian: A guru-like cross-cultural expert from Venice who makes it all happen!

July 25, 2021

“To have great art, we must commission it! In order to commission it, we must have great commissioners!” If there is one person in the Armenian world who could be credited with turning Frank O'Hara’s famous words into action, it’s Minas Lourian, who serves as director of the Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture in Venice, Italy.

Lourian was the catalyst behind Riccardo Muti’s recent “Roads of Friendship” concert in Armenia for the premiere of “Purgatory,” a commissioned piece by Tigran Mansurian. The maestro and his wife Cristina received the presidential Medal of Friendship, while Lourian was awarded with the Medal of Gratitude for their “significant role in the strengthening and promoting of cultural relationships between Armenia and Italy.”

H-pem sat down for an exclusive Skype interview to get valuable insights from the unconventional cross-cultural executive who has a deep knowledge of the Armenian-Italian community and a whole raft of stunning achievements under his belt.

Born in Lebanon and bred in Italy, Minas Lourian isn’t the usual kind of person we would come across in the Armenian cultural scene. Synergy is the key to his ability to deliver exceptional value and provide extraordinary experiences for Armenian and non-Armenian audiences alike. Linking different capabilities to one another, he strives to achieve local, national, international, cultural, and political goals through programs funded by European or Italian sources.

In April 2020, during the worst days of the COVID-19 pandemic, while an eerie silence reigned over Venice, Lourian was the man responsible for the chiming church bells all across the Dorsoduro District in commemoration of the Armenian Genocide, with a live stream from the Church of Santa Maria della Visitazione.

It was long before the pandemic that we first met Lourian on the premises of the Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture, where, after the screening of the film “Singing in Exile,” an Italian student was thanking him “for raising awareness through a most delicate depiction of a horrible story.”

“The goal is to deliver quality work that will last!” said Lourian, and we picked it up from there, following his tremendous success with the “Roads of Friendship” festival in Italy.

Here's the interview in its entirety!

Minas Lourian was the catalyst behind Riccardo Muti’s recent “Roads of Friendship” concert in Armenia (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)

Minas Lourian was the catalyst behind Riccardo Muti’s recent “Roads of Friendship” concert in Armenia (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)Loucig Guloyan-Srabian: Riccardo Muti took the Armenian musical world by storm when he conducted his Luigi Cherubini Youth Orchestra in Armenia for the premiere of Tigran Mansurian’s “Purgatory.” How were you involved in commissioning a piece based on Dantè’s “Divine Comedy?”

Minas Lourian: The Ravenna Festival is one of the greatest cultural festivals in Italy. It owes its fame to Riccardo Muti, who is one of the world's greatest conductors, his wife, Cristina, who is credited with the founding of the festival, as well as to very high level professional staff members. “Roads of Friendship” is an offshoot of the festival. Professional relationships are built on a foundation of mutual trust. My involvement in the festival follows a series of successful collaborations for over three decades. In 1996-1997, together with the festival's artistic director Franco Masoti, I co-organized a festival dedicated to the traditional and contemporary music of Transcaucasia within the framework of the Ravenna Festival, and arranged for the Yerevan Chamber Choir to perform Mansurian’s “Ars Poetica” based on three poems by Yeghishe Charents, and for other compositions by Mansurian and Giya Kancheli. In 2001 our center was the main catalyst in taking the La Scala choir and orchestra on a concert tour to Armenia under the leadership of Riccardo Muti. In 2018, I was invited to put together a concert for the millennial anniversary of San Miniato al Monte in Florence, where the premiere of Tigran Mansurian’s commissioned piece, “Seven Prayers,” based on Nerses IV the Gracious’ Havadov Khosdovanim (Հաւատով խոստովանիմ | I Confess with Faith), took place. During that time, plans were underway to organize the 700th anniversary of Dantè's death in Ravenna. The idea was to ask three living composers to write separate pieces that reflect the mood of the “Divine Comedy.” Along with Giovanni Sollima and Valentin Silvestrov, Mansurian was commissioned a piece, and I was asked to coordinate the implementation of the project.

The goal is to deliver quality work that will last!

L.G.S.: It’s amazing that the Ravenna Festival’s celebratory project has survived the pandemic and the Artsakh war…

M.L.: Dantè’s anniversary celebrations were scheduled to open in Ravenna in Sep. 2020, with performances of the newly commissioned works. The number of soloists, choir singers, and orchestra players was arranged in advance, and the composers carried out work within that scope. The pandemic not only postponed the concerts, but also limited the number of singers and musicians. We were aware that such a move would change the acoustic balance of voice and instruments, as well as the inner workings of a piece. Mansurian decided to compose anew. He retrieved the string parts, crossed out the wind instruments, expanded the percussion section by Far Eastern ritual instruments, and focused on the dialogue between vocalists and instrumentalists. Muti did not intervene in the process. He had absolute confidence in Mansurian and the quality of his music. Of the three pieces, he decided to conduct the “Purgatory” himself, which was a great honor. Even more so because he rarely performs contemporary works.

“The world premiere performance of Mansurian’s “Purgatory” in Yerevan will be followed by the Italian premiere in Ravenna, where Dantè was buried; a concert in Florence, where Dantè helped establish modern Italian language and literature, and in Verona, where he lived during his exile. Maestro Muti even promised to perform it with his Chicago Symphony Orchestra,” says Minas Lourian (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)

“The world premiere performance of Mansurian’s “Purgatory” in Yerevan will be followed by the Italian premiere in Ravenna, where Dantè was buried; a concert in Florence, where Dantè helped establish modern Italian language and literature, and in Verona, where he lived during his exile. Maestro Muti even promised to perform it with his Chicago Symphony Orchestra,” says Minas Lourian (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)L.G.S.: Tigran Mansurian is a great composer, no doubt, however, why did Muti choose him over others?

M.L.: Many artists are drawn to Dantè’s world, and many are afraid to be creative with his literary heritage because he is too powerful. Mansurian’s recent works proved that he could tackle Dantè's “Divine Comedy” musically. One cannot remain indifferent to his music rooted in spiritual wisdom. While he was delighted to have been commissioned by an outstanding conductor like Muti, he admitted some doubts along the way. Even after composing entire passages, he felt the work wasn’t progressing to his satisfaction. Fortunately, he conquered his fears, and the result is a masterpiece as attested by Muti.

Music and music making forms a vital terrain of cultural politics.

L.G.S.: There are several references to Dantè’s “Divine Comedy” in classical music. How does Mansurian bring a new dimension to the theme of “Purgatory?”

M.L.: It was an interesting coincidence that Mansurian was commissioned with a piece based on “Purgatory” because the concept does not exist in Armenian religious traditions. He always kept a copy of the book on his desk and used multiple translations to understand it. Eventually, he based his composition on two prayers. Despite being a contemporary classical composer, he immersed himself into the thirteenth century musical landscape of Dantè, as well as the Armenian medieval modal and monophonic music, to come up with a composition steeped in the atmosphere of inherently similar worlds. He gave detailed instructions on how the piece should be performed and what kind of mood it should evoke. Muti was amazed to discover the sheer magnitude of his work. It was obvious to him that Mansurian intended to create the steady pace that was maintained by Franciscan friars during ritual processions. The distinctive tempo sets the basic mood of the piece characterized by profound spiritual intensity, tinged with austerity, and rendered with a remarkable balance between the choir and orchestra.

The “Roads of Friendship” concert took place at the Armenian National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after Alexander Spendiaryan in Yerevan on July 4, 2021.

The “Roads of Friendship” concert took place at the Armenian National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after Alexander Spendiaryan in Yerevan on July 4, 2021.L.G.S.: What did the “Roads of Friendship” concert achieve in Armenia?

M.L: Music and music making forms a vital terrain of cultural politics. Muti is an international authority in the music industry, and therefore a reference for state institutions. His leading of the world premiere of a commissioned piece by Mansurian, one of the world’s greatest living composers, is a fantastic achievement of music production made possible through foreign funds, which is a major financial breakthrough in itself. Moreover, the “Roads of Friendship” concerts take place in cities recovering from war, with a message of peace and brotherhood. The decision to hold the premiere of “Purgatory” in Armenia followed the forty-four-day Artsakh war. The concert marked the second time in the twenty-five-year history of the “Roads of Friendship” that it returned to the same venue. Through our musical collaboration we attracted major media attention from Italy, and arranged for the journalists to be taken on an aerial tour of Armenia’s most iconic landmarks, also with references to the forty-four-day Artsakh war and reminisces of the Armenian Genocide.

L.G.S.: At the end of the concert Riccardo Muti was quoted as saying, “Every Italian has two countries, Italy and Armenia,” putting a twist on Sviatoslav Richter's iconic quote, “Everyone has two countries, one’s own and Italy.” What compelled the maestro to make such a statement?

M.L.: Muti said, “tonight” we feel a dual sense of belonging: Italian and Armenian. Rhetoric aside, and apart from his collaborations with musicians of Armenian origin, as well as La Scala’s memorable concert dedicated to the 1700th anniversary of the adoption of Christianity as a state religion in Armenia, the country also has biblical connotations for Italians. Armenia is the first Christian nation, and there were Armenian saints in Italy—like San Miniato of Florence. There was Armenian military presence in Ravenna during the Byzantine era, and the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia enjoyed relations with the Italian maritime republics. These memories remain in the subconscious.

To mark the 50th anniversary of its establishment, and for the first time in its history, The Tallis Scholars will perform a new commissioned piece by a living Armenian composer throughout next year. Tigran Mansurian is working on a composition based on a poem by Krikor Beledian, a living icon of Armenian literature in his own right (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)

To mark the 50th anniversary of its establishment, and for the first time in its history, The Tallis Scholars will perform a new commissioned piece by a living Armenian composer throughout next year. Tigran Mansurian is working on a composition based on a poem by Krikor Beledian, a living icon of Armenian literature in his own right (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)

L.G.S.: You organized a similar highly acclaimed concert in 2017 by inviting The Tallis Scholars to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the establishment of the Mekhitarist Monastery in Venice. Why was it important to have a cultural event like this in Venice?

M.L.: The Mekhitarists initiated a turning point in Armenian history and culture. Ever since they set foot in Venice and established their home on the Island of San Lazzaro, their impact has been significant and wide-spread. For Italians, the island has become synonymous with Armenians because of its continuous presence in Armenian life. The Mekhitarist Monastery has served as a bridge between the Eastern Christian culture of the Armenian Highlands and the European classical culture of Italy. Bridging the two cultures has been a major part of the Mekhitarist activities and it has played an immense role in the Armenian Renaissance.

The 300th anniversary of the establishment of the Mekhitarist Monastery coincided with the 450th birth anniversary of Claudio Monteverdi, which was being celebrated across Italy. Our center secured foreign funds to organize a concert dedicated to the Renaissance and Baroque musician by inviting The Tallis Scholars, the world-renowned a cappella choir from Britain, under the leadership of Peter Phillips. The concert took place at the St Mark's Basilica, and is still remembered with gratitude by the choir—which had always wished to perform in Venice, and by the city itself—which finds it increasingly difficult to afford hosting high quality performances, as an act of appreciation from an Armenian institution based in Venice.

The Mekhitarist Monastery has served as a bridge between the Eastern Christian culture of the Armenian Highlands and the European classical culture of Italy.

L.G.S.: What makes The Tallis Scholars concert in Venice worthy of recognition?

M.L.: One may wonder why we put so much effort into targeting foreign audiences in a foreign country. There are several reasons for this: one is political, because as Armenians, we want to make our presence felt in a cultural capital like Venice, where we have been rooted, established connections and gained trust—we owe it to the city to give back; another is strategic, since a thousand-strong audience learned about the Mekhitarist congregation, and its importance in the cultural scene of Venice, by choosing to attend The Tallis Scholars’ concert; a third is to make visible the existence of an Armenian professional institution— the Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture, on par with similar ones in Venice, with a primary goal to provide high-quality cultural experiences rather than make profits; and last but not the least, is to promote Armenian culture. As a token of gratitude for the splendid opportunity, The Tallis Scholars sang two Armenian songs: “Sirt im sasani” («Սիրտ իմ սասանի» | “My Heart Trembles”) and “Amen Hayr Surb” «Ամէն Հայր Սուրբ» | “Amen Holy Father”) in their repertoire of European classical masterpieces. Professional and full HD audio and video recordings of the concert provided by our center will soon be produced by the famous German ECM company, and will be televised to a global audience by international broadcasting corporations.

As a professional center in Venice, we add our contribution to the city’s contemporary offerings and meet the desire of world-class musical groups to perform in Venice. It’s our way of bringing attention to the best of Armenian music, as well as ensuring its propagation and continuity.

L.G.S.: At the beginning of our conversation you made a reference to cultural politics. How does it translate into action?

M.L.: As a professional center in Venice, we add our contribution to the city’s contemporary offerings and meet the desire of world-class musical groups to perform in Venice. It’s our way of bringing attention to the best of Armenian music, as well as ensuring its propagation and continuity. We're currently organizing an exceptional concert for the quinquennial International Congress of Byzantine Studies in Venice. How do we do this? Operating managers within organizations usually seek collaborations to advance their annual plans. We have the connections and expertise to exchange ideas and proposals, which in turn expands the scope of collaborations. A similar structure for music production should be set up for the Armenian Diaspora, where musical events are isolated initiatives, and are part of community gatherings rather than part of music production.

The Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture is an Armenian professional cultural institution in Venice (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)

The Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture is an Armenian professional cultural institution in Venice (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)L.G.S.: The Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture is generally viewed as being off the radar for many Armenians. What were the primary goals of the inception phase?

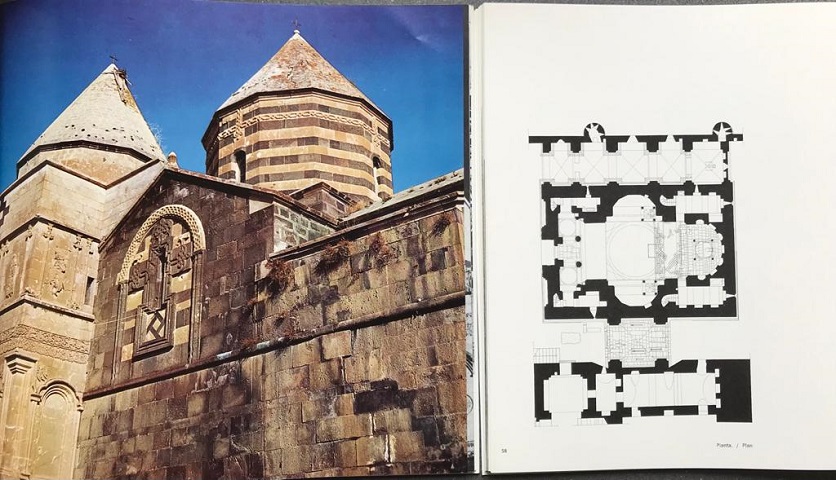

M.L.: The Center was founded in the 1960s by Italian and Armenian architects from Milan and Rome to study the influence of Armenian architecture on the development of Christian architecture in the Near East and the Romanesque architecture in the West. They organized more than forty scientific expeditions to take measurements and pictures of long-standing or crumbling monuments. It wasn’t an easy task, given that many of the monuments were in Turkey and Soviet Armenia. The systematic study of Armenian architecture as an important cultural expression, and the publication of relevant scientific material served as a warning against the risk of damage to the surviving but vulnerable monuments, especially in Turkey. Over the years, several teams were sent out to check on the monuments and assess the damage—yet another example of culture as a powerful tool to achieve “political” ends.

L.G.S.: Cultural strategies evolve over time to better fit their context. How did the Center keep up with expectations both at the Armenian and Italian level?

M.L.: The Center was spearheaded by the Como-based Manoukian brothers and architect Herman Vahramian, a brilliant innovator, who organized international symposiums dedicated to the study of Armenian thought, inviting some of the most distinguished twentieth century Armenian intellectuals to brainstorm through the meaning of the Armenian Diaspora in relation to Western influence. They discussed important anthropological, cultural, religious, and literary topics. Papers presented were subsequently submitted for publication under the title of “Diaspora della mente,” or “Diaspora of the mind,” and have a reputation for profound seriousness.

Historically, Venice was a hub of three vital communities: Jewish, Greek, and Armenian. Even though the Armenian community was relatively small, it was no less active until the last few decades. As an Armenian center based in a property under the auspices of the Mekhitarists, we’ve provided significant impetus to Armenian cultural and academic presence not only in Venice, but also at a national and international level. In contrast to the traditional Armenian milieu marked by community-targeted approaches, over the past thirty years, our center has played a remarkable role in securing a dynamic Armenian involvement in wider cultural activities.

The systematic study of Armenian architecture as an important cultural expression and the publication of relevant scientific material served as a warning against the risk of damage to the surviving but vulnerable monuments.

L.G.S.: What were the challenges you faced after taking over such a robust center for culture, heritage, and innovative research?

M.L.: I joined the Center in the early 1990s, when, upon completion of documentation related to Armenian monuments, and armed with all that knowledge, the Center embarked on the next stage of its project to prepare reconstruction and preservation plans. We have a team of specialists led by architect Gayanè Casnati— representative member of Europa Nostra—at the Polytechnic University of Milan, focused on developing conservation plans and finding the funding to implement them. It’s a huge and financially challenging task. It’s hard to convince potential Armenian donors to support the professional cultural sector, since most cultural commitments are considered to be charity services. There is also difference in attitudes between Italian and Armenian restorers, and the societal acceptance of foreign expertise in Armenia. Nevertheless, over the years, we’ve successfully secured funds from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to bolster the project, and have sent over forty experts to Armenia to locally train students in the techniques, methods, and ideas of conservation and restoration, whereby graduates received their Master’s degree from the Polytechnic University of Milan.

There are also political issues. Turkey is out of reach for all the well-known reasons, while an invitation from UNESCO to restore three Armenian monastic ensembles in Iran under the supervision of Italian experts is fraught with political obstacles because of the US embargo on Iran, which makes it hard to raise funds in the West. These are UNESCO sites, and the Iranian authorities are keen to secure the legacy of the country’s rich Christian heritage. My task was to play a coordinating role between Italian and Iranian experts, academicians and restoration groups. We must fulfill UNESCO’s criteria for prevailing international practices based on conservation rather than reconstruction— the latter unfortunately continues to be the norm in Armenia.

.jpg)

M.L.: There has been much debate on the issue of identity in the last decades. Unfortunately, Armenian identity is shaped by the Armenian Genocide and the psychological ramifications of the trauma. But we also have a centuries-old cultural heritage, and it should assume its rightful place in our national consciousness. We are part of a living culture and have the ability to communicate through creative expression. However, we can no longer afford to waste our efforts and resources on duplicated projects with less than optimal results. We believe that having prepared the ground for synergic cooperation, our center is offering a successful alternative.

We are part of a living culture and have the ability to communicate through creative expression. However, we can no longer afford to waste our efforts and resources on duplicated projects with less than optimal results.

We regularly receive cooperation requests from all over Italy. Some seek advice and sources on Armenian related topics, others—like foundations and municipal institutions with the financial means—are open to proposals within their areas of expertise, and together we outline Armenian-related projects. I believe success can only be achieved through a synergic approach. I think it’s very important to realize this, especially in today’s world—when the economy is down, the arts and culture are the first to feel the effects of budget cuts. In the Armenian reality, more often than not, Armenian initiatives are targeted to Armenian groups, and hence the need for Armenian sponsorship. However, Armenians shouldn’t ignore the possibility of using foreign funds to develop cultural programs designed to reach international audiences. We fail to realize that we are deeply rooted in the countries we live in, we pay taxes, and are entitled to receive grants for cultural projects. After all, culture is the most valuable asset for a nation like Armenia which lacks natural resources, geopolitical leverage, and economic competitiveness. It's important to establish centers of professional expertise in the Armenian Diaspora where the main focus has always been on community-based culture. To get such centers up and running, and to ensure their continuous operations, we need the ongoing support of Armenian donors.

Armenians shouldn’t ignore the possibility of using foreign funds to develop cultural programs designed to reach international audiences.

L.G.S.: Any practical advice on where to start with synergy?

M.L.: Since 2008 an international literature festival, called “Crossroads of Civilizations,” has been arranged in Venice by the Ca' Foscari University. I’ve had trouble finding foreign translations of Armenian literature to take part in the event. Our center organized a retrospective of Robert Guèdiguian's movies instead of presenting an Armenian author. It’s a fact that publishing houses have become global corporations. Many authors have won the Nobel Prize for Literature because they have been translated. There is a need for synergic cooperation between Armenia’s state institutions and diasporic associations to make such achievements possible. It’s high time we give it a thought, and promote the translation of contemporary Armenian writers into foreign languages. After all, a language lives and breathes through the act of translation, and an artistic expression of the genocide experience may have a more powerful influence on people’s opinions than any document.

.png) The Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture has been a major force behind the first concert of the Collegium Vocale Gent in Venice. The ensemble presented a program of Baroque music on the occasion of the 580th anniversary of the establishment of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. For the first time ever, a concert was held in the 15th century entrance hall of the building (Sala delle Colonne) for having the best acoustic for Schein's music (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)

The Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture has been a major force behind the first concert of the Collegium Vocale Gent in Venice. The ensemble presented a program of Baroque music on the occasion of the 580th anniversary of the establishment of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. For the first time ever, a concert was held in the 15th century entrance hall of the building (Sala delle Colonne) for having the best acoustic for Schein's music (Photo courtesy of Minas Lourian)I believe success can only be achieved through a synergic approach. I think it’s very important to realize this, especially in today’s world.

M.L.: I assumed the responsibility of a community leader in the prospect of developing synergic interactions and professional partnerships on a national and international level. While we often employ the word “community” to define the social structure of various Armenian diasporic societies, “Union of Armenians in Italy” is the term used to describe the Armenian presence in the country. It’s a legacy of the Armenian Genocide. In 1915, when the need arose to organize the admission and settlement of Armenian refugees in Italy, the Union acted as a mediator between the Italian state and asylum seekers from Turkey. It was recognized in 1955 by presidential decree as the sole legal representative of Armenians in Italy, which is a unique phenomenon in the history of the Armenian Diaspora—there are no political parties or dioceses in Italy, but only major Armenian historical institutions and congregations.

L.G.S.: How does the Armenian identity manifest itself in the Armenian-Italian context?

M.L.: We’re facing a new reality in Italy. Even before the Armenian Genocide there were families who conducted themselves in terms of their Armenian identity. There were Armenian institutions, which, like the Mekhitarist congregation in Venice and the Levonian Pontifical Seminary in Rome, served as beacons for generations of Armenians. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, we have newcomers from Armenia and Eastern Europe, who can bring new vitality and impetus to the community. We must put our differences aside and find common ground for coordinated and result-oriented efforts.

That said, it’s absolutely amazing that also through the editing support of our center, a community of a few thousand Armenians commissioned a team of historians from the University of Florence to carry out research into the declassified archives of the Italian Foreign Ministry. It’s the only Armenian community in the world that has successfully implemented the project of documenting, analyzing, and publishing fifty years of diplomatic correspondence on issues of interest to Armenians. The published volumes cover the years from 1878 to1923, and five further volumes are in preparation.

Our collective voices have been missing in international circles that often shape global views and attitudes toward Armenian issues.

L.G.S.: What about young Armenians’ sense of ethno-cultural belonging in Italy? What are the potentials, limits, and contradictions related to the promotion of youth-oriented policies and programs?

M.L.: Over the years, as a nation, our main focus has been on preserving the Armenian language. Little effort has been made to prepare and support professionals for roles like researchers, academicians, journalists, and translators. Academic centers for Armenian studies in Italy face the risk of closure due to lack of students. We’re heading towards a future where we will rely on influencers to make ourselves heard—their support is important, no doubt, however, our collective voices have been missing in international circles that often shape global views and attitudes toward Armenian issues.

It was just a hunch that led me to the discovery of a fund created one hundred and fifty years ago by an Armenian donor in Trieste. Since there are no Armenians left in the city, the fund is used to provide tuition for Italian students. The Center’s presence as a community anchor allows us to benefit from the fund and provide grants—however limited in number, to qualified Armenian students not necessarily raised in Trieste to pursue academic education at Italian institutions.

Hamazkayin YouthLinks Europe participants at the Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture in Venice, where they attended workshops in 2018 and 2019 (Photo: YouthLinks Europe)

Hamazkayin YouthLinks Europe participants at the Center for Studies and Documentation of Armenian Culture in Venice, where they attended workshops in 2018 and 2019 (Photo: YouthLinks Europe)

L.G.S.: Perhaps we need a new paradigm as an alternative to the traditional methods of preserving the Armenian identity (Hayabahbanum | Հայապահպանում). What would it be?

M.L.: We’ve always tried to preserve our language, religion, and culture out of fear of losing them. Conservation through traditional institutions and schools is the overwhelming reality in the diaspora. It’s not that efforts to preserve the Armenian identity were futile. But we’re out of touch with professional circles and aren’t well represented in most sectors. We haven’t created professional organizations and we don’t have professional references who can speak on our behalf or make us heard, especially in times of national crisis. As a matter of fact, we’re talking to ourselves and trying to justify ourselves with little interaction with the outside world.

The achievement of our objectives through synergic and coordinated activities is proof enough that we can engage in cultural, economic, and political activities in new ways. When you offer something new to young people, they get excited and feel empowered that they have something to say. You give them a new platform, with a renewed identity.

When you offer something new to young people, they get excited and feel empowered that they have something to say. You give them a new platform, with a renewed identity.

L.G.S.: Is there hope for innovation and regeneration? What are the standards to work to? What needs to be avoided?

M.L.: If not for hope, I would never have come this far. Innovation matters! The problem is that Armenian communities across the world use the same means to meet their goals and end up with the same inefficient results. Attendees of pan-Armenian conferences should be experts in their fields, capable of planning for the long-term in a meaningful way, outlining purposes based on shared fundamentals, and establishing foundations for fund-raising purposes to carry out their projects. Although attending such conferences can be an isolating experience for me, I use the opportunity to introduce our center’s innovative working approach for the benefit of our collective future.

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!