Between the ephemeral and the eternal: Levon Eskenian’s de/re-construction of Gurdjieff and Komitas

September 25, 2019

You do not see him on stage, yet Levon Eskenian has been taking his world-class Gurdjieff Ensemble to major festivals and music venues around the world, rendering ethnographically authentic music on traditional Eastern folk instruments and evoking the deep stirrings of ancient rituals. While invitations continue to pour in, we meet the man behind this unprecedented musical excavation, which has opened a new page in classical music.

Ever since John Cage found music in the silence that surrounds us, musicians have been deconstructing compositions to experiment with sounds. Musicology goes as far as to explore the role of the player’s movements in remodeling the musical structure of a piece, or to create a debate by playing different editions of a composition.

One man has taken the deconstruction of musical scores to a whole new level. Putting his diverse musical background into action, Levon Eskenian, the founder of the Gurdjieff Ensemble (founded in 2008), has been dissecting the inner makings of folk-based classical pieces to dig out authentic sounds and arrange them back into their original settings, while keeping the compositions intact.

“The Gurdjieff Ensemble takes many things into consideration: interpretation, performance style, ethnographic background, history, and all this, with honesty and objectivity. I think that's one reason why audiences in the West appreciate our performances.” Levon Eskenian, founder and director of the Gurdjieff Ensemble. (Photo: Andranik Sahagyan / gurdjieffensemble.com)

“The Gurdjieff Ensemble takes many things into consideration: interpretation, performance style, ethnographic background, history, and all this, with honesty and objectivity. I think that's one reason why audiences in the West appreciate our performances.” Levon Eskenian, founder and director of the Gurdjieff Ensemble. (Photo: Andranik Sahagyan / gurdjieffensemble.com)

The result is pure musical alchemy executed with precision and passion. Speaking in mysterious tongues, Eskenian’s arrangements of George Gurdjieff and Komitas make tantalizing connections between the ephemeral and the eternal, the mundane and the spiritual. As the past rhythmically plows its way through the centuries, even the most skeptical of listeners are not able to resist the temptation of walking through the doors of history and bowing in reverence to humble folk who carried precious tunes over mountains and deserts to courts, markets, fields, and monasteries.

Gurdjieff, the namesake of the ensemble, was himself a seeker of esoteric truths. He was obsessed with finding a method to achieve a higher level of consciousness in order to reach full human potential. His quest took him to the Caucasus, the Middle East, Central Asia, India, and North Africa, where he soaked in mystical experiences and musical traditions, which he used for his dance-like exercises.

.png) George Ivanovich Gurdjieff was a mystic, philosopher, spiritual teacher, and composer of Armenian and Greek descent, born in Alexandrapol (now Gyumri), Armenia. (Photo: religiousstudiesproject.com)

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff was a mystic, philosopher, spiritual teacher, and composer of Armenian and Greek descent, born in Alexandrapol (now Gyumri), Armenia. (Photo: religiousstudiesproject.com)Born in 1866 to an Armenian mother and a Greek father in the multiethnic town of Alexandrapol (now Gyumri), “Gurdjieff belonged to no tradition,” as Philip Marsden writes in his quintessential travelogue. For the British travel writer, “[Gurdjieff’s] own particular rootlessness could only have been bred in this region, in old Armenia and the Caucasus where the traces of antiquity could still be found among the ruins, and where the clash of ideas—dualist, Zurvan, Sufi, Christian, Islamic, Bolshevik-has made it more diverse, more dynamic, more dangerous than perhaps anywhere else on earth.”

On the surface, it would be hard to find parallels between the cosmopolitan Gurdjieff and the nationally imbued Komitas—the priest, the collector of thousands of Armenian folk and sacred songs, and one of the first to probe into the enigma of the Medieval Armenian notation system, only to fall prey to the mental trauma caused by the Armenian Genocide.

Yet, their paths couldn’t have been more similar. “Take the understanding of the East and the knowledge of the West—and then seek.” Having absorbed the wisdom of the East, Gurdjieff lived up to his famous quote and set up institutes in the West, to teach his method of the Harmonious Development of Man. Komitas had trodden the path before him by creating harmonies and polyphonic lines derived from authentic Armenian music and introducing them to Western ears. Both used a Western instrument, the piano, as a medium.

Eskenian’s delicately de/re-constructive approach to Gurdjieff’s and Komitas’ piano pieces has earned the Gurdjieff Ensemble a place at several major international music festivals. His arrangements of “Zulo” for traditional instruments took flight in 2016, after it was featured in the “Top of the World” compilation released by the prestigious Songlines Magazine. As a result, British Airways featured the track, along with Eskenian’s arrangement of Komitas’ “Akna Oror” («Ակնայ օրօր» | “Lullaby of Akn”) on all their flights for a year.

A Lebanese-born Armenian musician who even claims to be genetically connected with Komitas, Eskenian cut a low profile in Yerevan, where we met to discuss his unique craft and worldwide collaborations. “The Komitas album was described as reconstructing something from the past,” he explained, setting the direction of the interview that followed.

Check out videos from the Gurdjieff Ensemble below and share your impressions with us. For more songs visit the ensemble’s YouTube channel!

After a concert in Belgium a German couple offered support to the Gurdjieff Ensemble. “I wish we could have sustained sponsorships,” says Levon Eskenian, the artistic director of the ensemble, who has collaborated with different festivals and organizations around the world. He has also worked with the Gulbenkian Foundation and the Ministry of Culture of Armenia and is open for collaborations with Armenian organizations. (Photo: Andranik Sahagyan / gurdjieffensemble.com)

After a concert in Belgium a German couple offered support to the Gurdjieff Ensemble. “I wish we could have sustained sponsorships,” says Levon Eskenian, the artistic director of the ensemble, who has collaborated with different festivals and organizations around the world. He has also worked with the Gulbenkian Foundation and the Ministry of Culture of Armenia and is open for collaborations with Armenian organizations. (Photo: Andranik Sahagyan / gurdjieffensemble.com)

Loucig Guloyan-Srabian: The Gurdjieff Ensemble is known for its unconventional use of authentic instruments in playing Gurdjieff and Komitas. What was the source of this incentive?

Levon Eskenian: It was in 2006, that together with my wife, pianist Lucine Grigoryan, we first heard a recording of Gurdjieff played on classical instruments like the piano and the cello. We thought it was very connected with the psychology of Gyumri where Gurdjieff was born. It felt very close to me since it was also rooted in the culture of the Middle East.

Gurdjieff has more than 200 piano pieces with different names, like “An Armenian Song,” “A Kurdish Song,” “A Greek Round Dance,” “The Assyrian Women Mourners,” and “The Caucasian Dance.” We thought it would sound very natural if they were played on Middle Eastern instruments. Thus, the idea of considering the traditions of each of these pieces and arranging them for authentic instruments took hold. The Ensemble was formed to play Gurdjieff’s pieces, but it expanded to include Komitas and modern composers as well.

L.G.S.: The trend for emerging bands is exactly the opposite: There is a movement towards playing traditional melodies on modern instruments. What did it entail to dig deeper into the nuances and inner workings of folk-based classical music?

L.E.: I have studied Western music, the piano, composition, the harpsichord, and the organ, but I have always been interested in folk music. For this project, I started a research tour and listened to ethnic music. Being born in Lebanon, I already had an ear for the oud, the kanon, the daf, and the blul. My background helped me find out how Armenians would have played a song more than 150 years ago; how a Kurdish shepherd would have used the blul and the saz; how the “Sayyid Chant and Dance,” which is rooted in Arabic traditions, was rendered. I arranged the pieces based on these traditions.

I also studied the essays of Komitas, who described the instruments of the ashughs (աշուղ, “troubadour” in English). It gave me insight into the combination of instruments used at the time. Then I contacted musicians in Armenia, listened to the music they played, and thought that they were talented enough to understand and delve deeper into these traditions. We started rehearsing and the Gurdjieff Ensemble was born.

L.G.S.: Gurdjieff was almost anonymous in Armenia before you started playing his music. Even now his name sounds exotic. To what extent were people aware of his compositions? How well was he received?

L.E.: Unlike Komitas, whom we adore and whose music every Armenian knows, Gurdjieff's music was not quite known in Armenia and in Armenian communities. While Komitas is not very well known outside Armenia, Gurdjieff's music is performed around the world. Famous orchestras and musicians like the great jazz pianist Keith Jarrett have performed it. Also, his books were only recently translated into Armenian, though one can find them in almost every other language. Even though one of his books, Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson was written in Armenian, we don't know where the original copy is. After attending one of our concerts in 2008, Tigran Mansurian asked for a recording and sent it to Manfred Eicher, the founder of the famous label ECM Records, who produced it in 2011. We’ve performed in more than 20 countries and cities ever since.

L.G.S.: The aura that surrounds Gurdjieff is extraordinary. He has had a wide influence way beyond music. How did his multidisciplinary perspective enrich the world? Where would you place him on the scale of “most famous Armenians?"

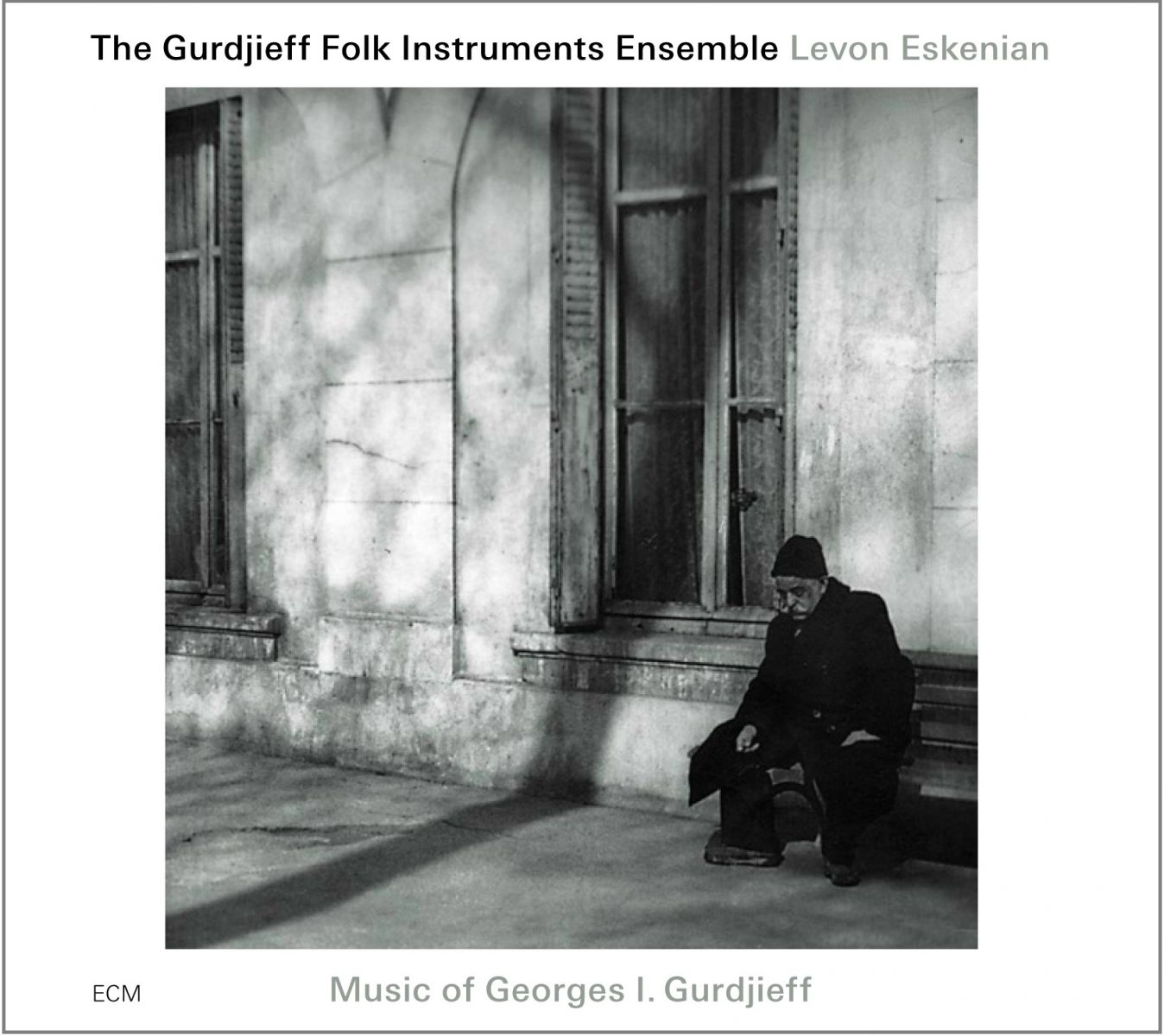

The Gurdjieff Ensemble’s debut album “Music of Georges I. Gurdjieff,” issued by ECM in 2011 was awarded the Dutch Edison’s Award among others, for its innovative recasting of Gurdjieff’s piano pieces for traditional folk instruments. (Image courtesy of the Gurdjieff Ensemble)

The Gurdjieff Ensemble’s debut album “Music of Georges I. Gurdjieff,” issued by ECM in 2011 was awarded the Dutch Edison’s Award among others, for its innovative recasting of Gurdjieff’s piano pieces for traditional folk instruments. (Image courtesy of the Gurdjieff Ensemble)L.E.: Gurdjieff is definitely considered one of the most famous Armenians. His methods are studied by many people. Even in the 21st century, big names like Steve Jobs were influenced by him. Jobs listed Meetings with Remarkable Men by Gurdjieff as one of the 14 books that most inspired him. Gurdjieff propounded his ideas in books, through different exercises and dance-like movements, which are meant to enhance concentration and take you out of the mechanical habits of life. He expressed the idea that our bodies go through waking-sleep stages: We are more awake during childhood, however, through time, when we start doing things mechanically, our mind, our body and our emotions become detached and we need to find a way to make them work together, to be aware of our surroundings, to think, and to remember. More than a century after Gurdjieff conceived his methods and daily exercises, they have enabled people to succeed in their fields. For example, an Executive Director of Shell has used Gurdjieff’s methods to develop a scenario planning approach to deal with crisis situations, which was later adopted by different companies.

L.G.S.: Did Gurdjieff’s Armenian background help him to develop insights into the human condition?

L.E.: Gurdjieff thought that we are not born just to live and die. He pondered about the human existence and the meaning of life and sought wisdom in different religions, disciplines, in medicine and science. During his childhood in Gyumri, he had encountered different traditions. He didn’t find answers to many questions in the books available to him. So, he sought grabar (գրաբար or classical Armenian) books, went to Etchmiadzin and Sanahin, even found old books from Ani. His quest took him further to Persia, the Middle East, India, and Tibet. On his journeys he interacted with different Christian brotherhoods, Muslims and Buddhist monks, and came up with his method of the “Harmonious Development of Man.” He returned to Armenia, but escaped from the Soviet Union to the West, where he founded an institution in Fontainebleau near Paris, as well centers in the U.S. and Britain. His students propagated his methods and opened centers around the world. Gurdjieff foundations and institutions exist in every major city in the U.S., Canada, South America, Australia, Europe, the Middle East, even in Asia and Africa.

.png) There is a growing interest in the Gurdjieff Ensemble’s 18 Komitas tracks which take back the composer’s piano pieces to their folkloric settings. “When a major recording company like ECM which is known for its selective taste releases a new CD, it is distributed all around the world and garners media attention,” says Eskenian. (Image courtesy of the Gurdjieff Ensemble)

There is a growing interest in the Gurdjieff Ensemble’s 18 Komitas tracks which take back the composer’s piano pieces to their folkloric settings. “When a major recording company like ECM which is known for its selective taste releases a new CD, it is distributed all around the world and garners media attention,” says Eskenian. (Image courtesy of the Gurdjieff Ensemble)L.G.S.: How does Gurdjieff’s music reveal his philosophy? How do you relay it to the audience?

L.E.: What Gurdjieff bequeathed to us forms one inseparable whole. Everything is connected: his dance-like movements, his music, his books, and his exercises. To be able to understand and perform his music, you need to immerse yourself in his world. You also need to study and understand the Armenian, Assyrian, Caucasian, Kurdish, Persian, and Arabic traditions that he encountered.

L.G.S.: Gurdjieff’s pieces are composed for the piano. Has he hinted that they could be played on ethnic instruments as well? How do you take his music back to its ethnic roots?

L.E.: In the 1920s, after a concert in France, it was announced that Gurdjieff's music would be played on 40 authentic instruments that the composer had collected during his travels. The project never materialized. We do not have instructions about the use of these different instruments, but the idea was always there. Gurdjieff remembered the different pieces he heard through his journeys and named them after their sources. When you hear a piece, you can tell if it's Armenian, Kurdish, or Arabic.

He was also quite realistic and objective when he dictated pieces to his student, Thomas de Hartmann. It’s true that the use of authentic instruments is based on my research, but his music gave this direction as well.

L.G.S.: Your second passion is Komitas. You take his music out of its classical mold to recreate the raw sounds that he used to hear on the Armenian highlands. How does this U-turn take place? How do you bring out those ancient sounds and how do you put a new touch to the melodies?

L.E.: We have a quote from Tigran Mansurian on our website, which says: “This is a unique experience, something that occurs inside the folklore-composing art relationship. The fabric of Komitas’ compositions is illuminated by the deployment of the folk instruments.” Komitas collected dance songs, folk songs, labor music, and music for ceremonies. But the pieces that he composed for the piano are mostly dances. “Msho Shoror” («Մշոյ շորոր» | “Coquetry of Mush”) is a series of dances that the Armenians danced during their pilgrimage to the Surb Karabet Monastery, which was destroyed after the genocide. We cannot trace back these dances. However, according to Komitas, they date back to pagan times and were orally transmitted. We also know that the Church adopted the kshots (flabellum) and burvar (censers), which were used in pagan rituals. So, we play these instruments in “Msho Shoror,” along with the Msho tmbuk, a big percussion instrument, which is no more in use. We tried to reconstruct it from a photo and different replicas, using goatskin and walnut wood.

Moreover, Komitas mentioned the source instruments that the pianists should evoke while playing these dances. For example, “Yerangui” must be played in the style of duduk and tar. "Marali" should be played in the style of tar and dap. “Het U Araj” in the style of dhol, pku, and tmbuk, and “Msho Shoror” in the style of zurna, duduk, and tmbuk. I took these as basic solo instruments and rearranged the pieces objectively, keeping Komitas intact. Only the instrumentation is different. It was amazing and surprising for me to see how delicately, faithfully and objectively he had preserved the sounds. As a result, we have very unique piano compositions with very unique piano structures and a new language in classical music.

Komitas transcribed and arranged over 3,000 pieces of Armenian folk music, of which only about 1,200 survived. (Photo: Komitas photographed in Constantinople, 1912. Courtesy of the Komitas Museum-Institute)

Komitas transcribed and arranged over 3,000 pieces of Armenian folk music, of which only about 1,200 survived. (Photo: Komitas photographed in Constantinople, 1912. Courtesy of the Komitas Museum-Institute)L.G.S.: It’s good to know this because some critics object that Komitas altered the folk music genre and made it more classical…

L.E.: We need to differentiate between Komitas the collector, Komitas the scientist, and Komitas the composer. Komitas collected thousands of songs which are published in 12 volumes. He wrote some of these songs in the Armenian notation system. He also composed classical music, choir pieces, and folk-piano pieces based on some of these songs. These are not just arrangements, but also real compositions. He left much of the music intact because his intention was not to fuse Western harmonies with Armenian melodies, but to create modality, rhythms, and harmonies that are totally derived from the Armenian melodic line. And he tried to arrange them for classical instruments. So, these rhythms really exist, and when a pianist plays these pieces without studying the Armenian rhythms, you might get a different, more westernized interpretation. The existence of Armenian rhythms was obvious to me and that was one of the reasons why I decided to arrange back—to recreate those rhythms without making any changes.

L.G.S.: Spiritual and folk music are mutually interconnected not only in Gurdjieff’s music, but also in Komitas’s compositions. Are there commonalities between the two composers in this regard? What patterns can we detect in the music you perform?

L.E.: According to Komitas, Armenian spiritual music is connected with Armenian folk music. If you change the tempo of a church ritual, you get folk music, and vice versa. There is spirituality in Armenian folk music; a sense of deep concentration that allows you to focus on yourself, on your surroundings, on nature, and on God. For example, “Lorva Gutanerg” (“Plough Song from Lori”) opens with praise for God. It’s difficult to interpret the music of Komitas when you’re not in real contact with these sources; when you’re cut off by time and live an urban life.

Imagine arranging music, which is not composed for the stage, but for labor. “Lorva Gutanerg” is meant to be sung to the oxen to make them plow the fields. To bring it to the stage means to move it to another environment. This could be very dangerous: You might kill the music. You need to create a very special environment for the sounds to help them live like the fish in an aquarium. Gurdjieff opened up many doors to understand the music of Komitas, not only for me, but also for the musicians of the ensemble. Once, we were even discussing how we could have performed Komitas if we hadn’t studied the music of Gurdjieff and his methods of objectivity; of keeping yourself out. Because, you are already there, creating the music and bringing it to stage. As a musician, you're just a vessel between nature and people, between God and people, and you need to take that responsibility.

The Gurdjieff Ensemble playing Komitas at the Holland Festival in 2015. (Photo: Sevag Seropian)

The Gurdjieff Ensemble playing Komitas at the Holland Festival in 2015. (Photo: Sevag Seropian)

L.G.S.: Listeners can immediately detect the unmistakable touch of the Gurdjieff Ensemble. How do you achieve this? What does it tell about the music itself that resonates with people?

L.E.: When we rehearse a piece, we try to hear every tiny vibration and we try to connect these vibrations. We also try to connect with each other and try to feel each other. We have hardly made any changes in the ensemble—the musicians enjoy playing together and our purpose stands above commercial considerations. It’s true that we play on stage and get paid, however, we always tend to remember that for thousands of years, music was a way of life for people. It wasn't meant to be brought on stage to generate income. And of course, Gurdjieff's method had an impact on our perception of ourselves and on the music that we make. You must be honest with yourself, with your environment, and with your art.

As a musician, you're just a vessel between nature and people, between God and people, and you need to take that responsibility.

- Levon Eskenian

L.G.S.: The famous adage that music brings people together seems to lose some of its weight when it comes to authorship in folk music, which is often a bone of contention among people who share the same geographical area. What identity markers should we use to define the true origin of a certain piece of ethnic music?

L.E.: Any piece of folk music derived from ethnic sources is recognizable through careful listening and analysis. Yet, arguments existed even at the time of Komitas, who said, if the Armenians have their own unique language and alphabet, unique accents and rhythms, then they can have their unique music as well. But still, people with different ethnicities can have a common musical language that they can share, or can create something together. I believe that music can bring people together because it's a very common universal language.

L.G.S.: Let's talk about the Hewar project. The Gurdjieff Ensemble is an ethnographic group, while the Hewar Ensemble [Hewar meaning dialogue in Arabic] plays a fusion of jazz, Western classical music, and Arabic music. How do these diverse groups meet to create harmony? What is the significance of your collaboration?

L.E.: Our ensemble plays ethnic music, but it's also considered to be classical because Komitas is, after all, a classical composer. The idea of collaborating with the Hewar Ensemble, which consists of Syrian musicians, took shape in 2015. We, as Armenians, have a feeling of gratitude towards Syrians, who saved thousands of survivors of the Armenian Genocide. Now that Syrians are scattered all over the world, the perception about them is that they are refugees. However, the world should know that Syrians once gave refuge to a whole nation. I thought we should bring this into focus and proposed the idea to the director of the Morganland Festival, Michael Dreyer. We contacted the Hewar Ensemble, which has some great musicians like Kinan Azmeh, Dima Orsho, and Issam Rafea, and came up with this idea of having an Armenian composer and a Syrian composer writing new pieces to be played together by the two ensembles. Tigran Mansurian and Issam Rafea were happy to write new pieces for us. Mansurian’s song, “Tun Ari” («Տուն արի» | “Come Home”), says the war will end sooner or later and people will call on refugees to return home. I also arranged “Tamzara” (transcribed by Maro Nalpantian) and some Komitas pieces like “Garun a” («Գարուն ա» | “It is spring"), for joint concerts.

I believe that music can bring people together because it's a very common universal language.

The mixture of classical and Armenian traditional instruments has opened up a new page, a post-modern style, in classical music. Our first concert was held at one of the most responsive stages in the world, the recently built Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, and it was very well received.

The idea of collaborating with the Hewar Ensemble took shape in 2015, as an expression of the Armenian people’s gratitude towards the Syrian people, and the ensemble’s wish to bring the plight of Syrian refugees into focus. Their concerts, a mixture of classical and Armenian traditional instruments, have opened up a new page in classical music. Here, the two ensembles are photographed at Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. (Photo: Miek Reichert)

The idea of collaborating with the Hewar Ensemble took shape in 2015, as an expression of the Armenian people’s gratitude towards the Syrian people, and the ensemble’s wish to bring the plight of Syrian refugees into focus. Their concerts, a mixture of classical and Armenian traditional instruments, have opened up a new page in classical music. Here, the two ensembles are photographed at Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg. (Photo: Miek Reichert)L.G.S.: This enthusiasm for ethnographic music is truly refreshing. Is it because the music world is being drained of energy or is it simply rediscovering ancient dynamics?

L.E.: There is a lot of confusion about ethnographic music in the world today, especially in the West, where everything from authentic music to bands playing on the guitar and the accordion are categorized under “world music.” The Gurdjieff Ensemble takes many things into consideration: interpretation, performance style, ethnographic background, history, and all this, with honesty and objectivity. I think that's one reason why audiences in the West appreciate our performances. Another reason is that in classical music, there is a tendency now to favor our part of the world as source material. The West has only recently discovered Armenian music. Frank Scheffer, who has filmed interviews with great classical composers like John Cage, Pierre Boulez, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, wants to make a music documentary to find out how the archaic and the modern are intertwined in Armenian music. Soon many composers will turn towards Armenia for sourcing material and new sonorities. This will open a new page and will be a continuation of what Tigran Mansurian started. Western media has described Komitas as a torn page from history that is ready to be put back in place.

In classical music there is a tendency now to favor our part of the world as source material.

L.G.S.: As a Lebanese-Armenian living in Armenia, you have created an ensemble that has gained international exposure. Usually it’s the other way around: Artists from Armenia travel abroad to fulfill their dreams. How do you feel about this experience?

L.E.: I believe that if your path leads you to the highest point of success, then it doesn’t matter where you live; especially in the 21st century, where everything is accessible. I have chosen to live in Armenia because I cannot separate myself from Armenian culture. I travel to different countries, but when I come back to Armenia, I feel that I belong here, that my role is to act as an intermediary between Armenians and other cultures.

L.G.S.: What would be your advice to young musicians who use ethnic or folk music as source material?

L.E.: To be dedicated to what they’re doing; to be honest with the material they’re using; to be honest with themselves and to question themselves. To do research—to study not only Armenian music, but also the music of different ethnicities, like Komitas did, to understand and define Armenian music; and to dig deeply.

As Komitas said: “Mtir khoruh, Gtir noruh, Vaneh hinuh, Baneh minuh” («Մտիր խորը, Գտիր նորը, Վանէ հինը, Բանէ մինը» | “Dig deep, Look for the new, Ditch the old, Make the one”).

Fresh from their concert at the Gullbenkian Hall in Lisbon, the Gurdjieff Ensemble will stage three concerts on Wed., Sept. 25, in Chicago, at the Old Town School of Folk Music; Fri., Sept. 27, in New York, at Peter Jay Sharp Theatre, and Sun., Sept. 29, in Pasadena, at the AGBU Vatche & Tamar Manoukian Performing Arts Center (All concerts are at 7 p.m.).

Video

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Catherine Dedeyan

04 Jan, 2020 17:08:44 Edited

Beautiful interpretations, but somehow soulless.

0

Reply