‘Critical Distance’: Raffi Joe Wartanian challenges himself to make more with less

November 29, 2019

Armenian-born, Baltimore-bred, world-traveled, Raffi Joe Wartanian, digs deep in his new album, “Critical Distance,” which is expected to drop in time for Armenian Christmas. We had a chance to chat with Raffi about the record’s all-acoustic sound, the magic of the oud, and which tracks his grandmother, Knarig, loves jamming to!

Writer, musician, activist, and friend of h-pem, Raffi Joe Wartanian, wears many hats. After a six-year hiatus from his debut album, “Pushkin Street,” he is back with a fresh set of tunes, cementing another title to his ever-growing repertoire: instrumental recording artist. His upcoming album, “Critical Distance,” is a 40-minute acoustic journey through the many cultural and artistic styles, sounds, and inflections that have influenced the multitalented artist. Though the record is nearly complete, a 30-day crowdfunding campaign is underway to bring it to the final stage. If you’ve ever wondered what Armenian and Appalachian fusion sounded like, “Critical Distance” is your answer.

Lilly Torosyan: “Critical Distance,” is a wonderfully explosive fusion of different sounds, most prominently, those of Armenian music and of the cultural region of Appalachia. What pulls you to these two “genres,” which themselves are amalgams of various styles that informed and influenced their own distinct sound(s)?

Raffi’s debut record,“Pushkin Street,” where each story was inspired by a different story in the singer’s life. (Graphic courtesy of Raffi Joe Wartanian)

Raffi’s debut record,“Pushkin Street,” where each story was inspired by a different story in the singer’s life. (Graphic courtesy of Raffi Joe Wartanian)Raffi Joe Wartanian: First of all, thank you to h-pem for taking the time to support innovative Armenian ventures around the world. I’m honored to be part of that conversation.

What draws me to the music of Armenia and Appalachia is the natural process of engaging with the places my family has known as home. My grandparents and great-grandparents come from Adana, Hajin, Zara, and Mersin by way of Kharpert. Like many from Western Armenia who survived the genocide, they eventually resettled in Beirut, where my parents were born. After studying in Soviet Armenia, my father was offered a job in Baltimore in the 1970s. He only planned to stay for a few years before returning to Beirut, but then the country unraveled during the Lebanese Civil War.

I describe this migratory path because the compositions of “Critical Distance” reflect the music of the spaces my family has lived. As Armenians from the Levant and the Armenian Highlands, the sounds of Armenian, Greek, Turkish, Arabic, French, and many other styles of music were prevalent in our home. Visiting family in Beirut most summers of my childhood meant a deeper appreciation for the way those traditions could coexist. Growing up in Baltimore, I found myself in another stylistic kaleidoscope built on rock, blues, soul, and bluegrass. I played in groups that performed funk, soul, and old-time Appalachian folk songs. All of these sensibilities shaped how I listen to and create music.

L.T.: Genre-bending, testing, and melding has been a forte of yours for awhile, as noted in your debut album, “Pushkin Street.” What compelled you to shift gears this time to an instrumental album?

R.J.W.: From a creative perspective, I wanted to challenge myself to try something different. This meant telling a musical story through an approach distinct from my first album, “Pushkin Street.” While “Pushkin Street” was rambunctious, loud, and absurd, “Critical Distance” is meditative, observant, and subtle. With “Pushkin Street,” I sang lyrics accompanied by chords, licks, and solos. In “Critical Distance,” my goal was to let the instrument sing. To help achieve this, I engaged new techniques—arpeggiation, rasgueado, odd-time signatures, and more—that would facilitate this.

Music was not spared during the rising impact of technology on our lives. It seemed that every day, a new pedal, effect, or sound was created. I felt like the technology was creating a separation between myself and the music, and that there was an implication that the instruments alone were not enough to produce a beautiful sound, and thus had to experience an intervention from technology to be worthy of performance and production. In short, I wanted to return to the origins of music, and challenge myself to make more with less, to push myself to maximize what I could express just with acoustic instruments. Any fan of flamenco, oud, or rebetiko can attest that the masters of these forms take their instruments to unprecedented heights. I, too, am inspired by their artistry, and this project, “Critical Distance,” is, in a way, an homage.

From a logistical perspective, since releasing “Pushkin Street” in 2013, I have lived in Yerevan, Los Angeles, and New York City. Creating another album like “Pushkin Street” would not have been practical. I could not take my instruments, amps, or other equipment around with me, and build bands. It was, however, more practical to travel with one or two acoustic instrument(s). They make for more natural travel companions.

L.T.: Describe the process of making “Critical Distance.” How did the idea of a collaboration with MB Gordy and Jake Leckie come about?

R.J.W.: An instrumental composition is a very personal and raw form of expression, so starting to share with others was a bit nerve-racking. I first approached Jake because we were housemates and friends in college. He’s an incredible musician, and once I decided to record some demos in my living room, he was the first person with whom I shared to gauge his interest. His enthusiastic response gave me hope that I was on to something promising.

Jake had previously worked with MB, and thought he’d be great for the project. Once I learned about MB’s accolades as a Grammy Award-winning percussionist who has played with many of my heroes (Bill Withers, Frank Zappa, and Neil Diamond among many others), I knew I was fulfilling a lesson taught to me by my oud teacher, Ara Dinkjian: surround yourself with the best. Jake and MB’s performances on the record speak for themselves. What a privilege to have their sound fill the album’s airwaves.

(L-R) MB Gordy, Raffi, and Jake Leckie. (Photo: Anastasia Italyanskaya)

(L-R) MB Gordy, Raffi, and Jake Leckie. (Photo: Anastasia Italyanskaya)L.T.: Speaking of Ara Dinkjian, he is one of the world’s foremost oud players, and at one time, was your instructor. In a time when fewer and fewer artists are picking up this wonderfully ancient and versatile instrument, you have done the opposite: As a Fulbright Fellow, you chose to study the oud at the Komitas Conservatory in Yerevan and have engaged in multiple projects about the instrument since. What draws you to the oud?

R.J.W.: I had seen the oud here and there in Lebanon and at various Armenian events in the U.S. But it wasn’t until I heard Ara Dinkjian’s 2006 album, “An Armenian in America,” that I began to feel the magical potential of the instrument. I was, and still am, drawn to the instrument’s earthy sound, its woody timbre, and its captivating role in the history of Armenian music. The fact that the tuning of oud strings is different from a guitar meant that I could explore different harmonic and melodic possibilities. The oud, which I started to study in 2012, is also fretless. This means an abundance of microtones, which guitarists can only find by bending notes or playing with a slide (a glass or metal cylinder placed on the fretting finger).

L.T.: As a multiplatform storyteller, you delve into multiple mediums, such as music, poetry, and creative writing. Since your debut record, you have been busy creating content in all of these formats, but have not released an album of your own original compositions since then. Why now?

R.J.W.: I think of music as one piece of my broader personal mission, which is to tell stories that engage my passion for social justice, creativity, and innovative institutions. After “Pushkin Street,” I wrote articles, published a textbook of Armenian oud music, and taught in a jail, hospital, and university. Along the way, I began composing the pieces that would ultimately become “Critical Distance.” This period of creation was one of deep personal reflection, of letting go and coming to terms with some of life’s harsh truths. I think that sense of reflection, surprise, and expression comes through in the music.

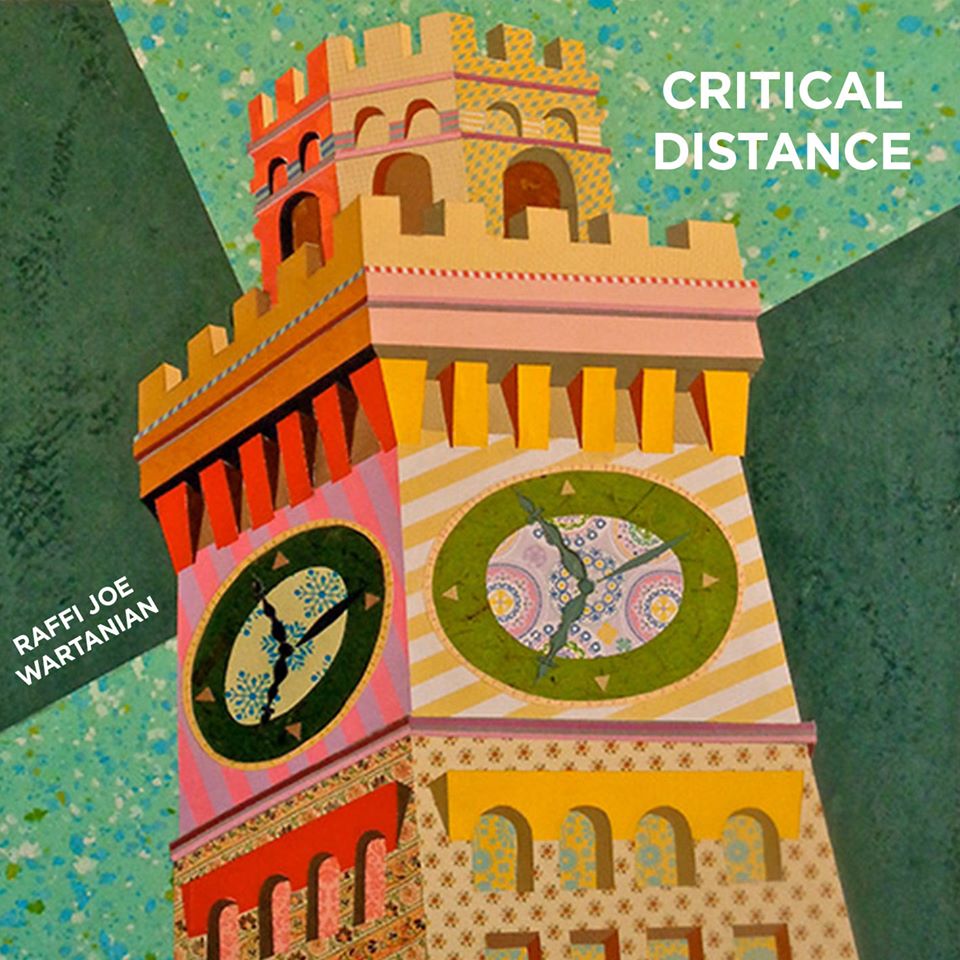

The album art for “Critical Distance” is by Baltimore-based Greek artist Minas Konsolas. It provides a colorful depiction of the Bromo Seltzer Tower, an iconic Baltimore building built in the early 1900s. “With the indigenous Armenian lands of eastern Turkey eradicated of my Armenian ancestry and my parents hometown of Beirut destabilized by civil war, the city of Baltimore offered something that my family could not find elsewhere: a stable sense of home, a place that could welcome us without falling apart,” Wartanian said. (Graphic courtesy of Raffi Joe Wartanian)

The album art for “Critical Distance” is by Baltimore-based Greek artist Minas Konsolas. It provides a colorful depiction of the Bromo Seltzer Tower, an iconic Baltimore building built in the early 1900s. “With the indigenous Armenian lands of eastern Turkey eradicated of my Armenian ancestry and my parents hometown of Beirut destabilized by civil war, the city of Baltimore offered something that my family could not find elsewhere: a stable sense of home, a place that could welcome us without falling apart,” Wartanian said. (Graphic courtesy of Raffi Joe Wartanian)

L.T.: When I interviewed you for “Pushkin Street,” you said that your grandmother’s favorite track was “Millard County Jail,” (It’s my favorite, too—gave me some Gogol Bordello vibes). Does she have a favorite with this album?

R.J.W.: My grandmother, Knarig, loves any song with bursts of emotion. In terms of “Critical Distance,” this means she especially enjoys the pieces which feature rasgueados, a technique in flamenco guitar in which the guitarist uses his/her plucking hand to strike the strings in a fanning motion. The result is a dramatic, percussive attacking sound. The way these appear in “A Whistle in the Desert” and “Escape” makes those tracks my grandmother’s favorites.

For a taste of “Critical Distance,” check out this one-minute sample, then head over to the album’s Indiegogo page to support the crowdfunding campaign. Missed our review of the album? Check it out here!

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!