Essay | That’s not Armenian! Encounters with language purists past and present

August 05, 2022

Did you know that the Armenian word for pencil, մատիտ (madid), comes from the Italian matita, or that the word for cup, գաւաթ (kavat), has Greek origins?

Etymology can be fun. Some of us relish in exploring the derivations of words! But how far back can you trace your language history?

Jennifer Manoukian has taken this passion one step further: while writing a dissertation on the emergence of Standard Western Armenian, she has found parallels between the ways we think about purity in Armenian today and the ways it was thought about in the nineteenth century.

Based on extensive research and with a penchant for surprising revelations, she makes a clear distinction between the challenge of pursuing purity in the written form of Standard Western Armenian as opposed to verbal communication, reflecting upon the living reality of the language we speak and favoring a more lenient approach towards the vernacular.

Check out her electrifying essay submitted exclusively to h-pem and let us know what you think in the comments below!

| Writer's name | Jennifer Manoukian |

| Occupation | Researcher; translator |

| City/Country | Los Angeles, Calif. |

| About the writer |

|

Whether they are from relatives, teachers or online commenters, appeals to use “pure Armenian” (մաքուր հայերէն) seem to be all around us. In the corners of the world where Armenian speakers can be found today, “pure Armenian” can mean many things but usually refers to a form of the language stripped of all pesky loanwords from the dominant languages of their particular countries: English for Armenians in the United States, French for Armenians in France, Arabic for Armenians in Lebanon, and so on. While thinking of language in terms of “pure” and “impure” may not seem all that unusual to an Armenian speaker, it is certainly not universal. As English speakers, we know this firsthand. How many times have you been told not to say restaurant, algebra or pajamas, words that you may not even be aware have been borrowed from French, Arabic and Hindi? Probably never. But how many times have you been made very much aware that չոճուխ (chojoukh), ինթերնէթ (internet) and մերսի (merci) have been borrowed from Turkish, English and French and have no place in your Armenian? Probably too many finger-wags and furrowed brows to count.

Where does this hostility to loanwords come from? To answer this question, we need to travel back in time to mid-1700s Venice. A seemingly unlikely spot to begin, Venice occupies a very special place in the history of Armenian trade, education and printing. For us, the city is important for a lesser known but no less important reason: it is where we find the first stirrings of what anthropologists call a purist language ideology. A language ideology is a technical term used to describe something that we all nurture in the privacy of our own minds as individuals and often share as linguistic communities: “beliefs, feelings, and conceptions about language structure and use.” A purist language ideology is, then, the belief that purity not only exists and is a desirable quality for a language but also that it is the responsibility of speakers to use language in a way that bars entry to “impurities,” however they may be defined at a given time.

A time before a preoccupation with purity

.jpg) Statue of Armenian poet and troubadour Sayat Nova in Gyumri, Armenia (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Statue of Armenian poet and troubadour Sayat Nova in Gyumri, Armenia (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)While this ideology is deeply ingrained in the minds of Armenian speakers today, it has not always been this way. In fact, prizing purity is much more of a novelty in Armenian linguistic history than we might expect. For as long as there have been Armenian speakers, those speakers have been borrowing words from people who have crossed their paths. Perhaps the most familiar example to us today of an earlier, more permissive approach to loanwords is the poetry of the eighteenth-century bard Sayat Nova. His verses are teeming with words shared by the different linguistic communities of the South Caucasus. Going even further back in time, the literary historian Michael Pifer has recently unearthed a similar melding of languages in the work of poets writing in Middle Armenian in medieval Anatolia. Although today we might be quick to overlay our modern, nationally conceived conceptions of language onto the work of these poets and raise our eyebrows at what we perceive as the “Persian,” “Georgian,” “Arabic” or “Turkish” words that abound in it, this impulse only exposes the wheels of our purist language ideology in motion. These poets lived at a time before the emergence of modern national identities, before words were treated like the patrimony of individual nations and before concerns about purity dictated how language should be used.

When we look back at the history of Armenian, it is crucial to distinguish between spoken and written language. Today many—especially those who have been formally educated in Armenian—speak the language in a similar way to how they might write it or how they might read it in a book. But for more than a millennium, there was a sharp divide between the spoken and the written both in the forms they took and in perceptions of them. Of course, Armenians were not forbidden from writing as they spoke. Sayat Nova and the medieval Anatolian poets did just that. But convention dictated that the most illustrious, most respectable, most distinguished form of written Armenian was Classical Armenian, or գրաբար (krapar). Before the nineteenth century, the vast majority of Armenian manuscripts and printed books were composed in this variety of the language, including the fifth-century Armenian translation of the Bible and other early religious texts. Classical Armenian is still used in the liturgy of the Armenian Church and—you might be surprised to learn—is just as incomprehensible to you sitting in the pews today as it was to most uninitiated Armenians in the past. Thorough knowledge of Classical Armenian has always been limited to the highly educated and would have required years of schooling, to which most Armenians gained access only within the past 150 years.

But even those who could read and write in Classical Armenian did not grow up speaking it nor did they use it at home with family or out and about with friends. These were the domains of their own regional varieties of Armenian—distinct from Classical Armenian and from one another in their grammar and often in their vocabulary—or other languages entirely. Unlike today where language is imbued with tremendous symbolic value and seen as a pillar of identity, Armenian identity before the 1800s was more inextricably linked to religious belonging. Simply a tool for communication, the language you spoke—whether it was a variety of Armenian or Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic or even Russian or Hungarian—was considered to be of little consequence to your Armenianness as long as you were part of the Armenian Church. Little attention, in other words, was paid to the spoken word.

.jpg) Bust of linguist and etymologist Hratchia Adjarian in Yerevan (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Bust of linguist and etymologist Hratchia Adjarian in Yerevan (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)Unfettered by the rules and regulations that governed written language, the lexicon of spoken forms of Armenian has throughout the ages been defined by its freedom to change, swelling and shrinking in time with social and political changes in lives of their speakers. Many of these changes have come as a result of the new cultures that speakers have encountered through migration, conquest, trade, intellectual exchange and everything in between. For example, Hratchia Adjarian, one of the foremost Armenian linguists, wrote about the influx of Arabic medical and botanical terms into spoken Armenian in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. This was a time when Arabic-speaking intellectuals were at the cutting edge of science and medicine and their new knowledge was being spread across the region, including to Armenians. From Adjarian, we also learn about the Latin, French and Italian administrative and governmental terms that made their way into spoken Armenian in the Cilician Kingdom in the midst of the Crusades and the increased European contact they brought. These words filled gaps in the Armenian lexicon of the time, which is one of the main motivations that linguists cite for borrowing. Fixed and frozen in time, Classical Armenian remained largely closed to these new terms and few traces of loanwords from these periods remain today in any form of spoken Armenian, having dissipated and eventually disappearing once cultural contact waned. New waves of cultural contact and borrowings quickly took their place, leaving their own mark on the spoken Armenian of their time. Having been preserved through writing and bearing the mark of these later waves, the work of Sayat Nova and the medieval Anatolian poets are rare in that they mirror the ways Armenian was spoken in their particular historical moments and show us that—although the languages loaning the words might have changed—our impulse to integrate words into our spoken Armenian from the languages around us has not.

The eighteenth-century origins of the purist preoccupation

View of San Lazzaro degli Armeni in Venice, by Giuseppe Bernardino Bison (Photo: dorotheum.com)

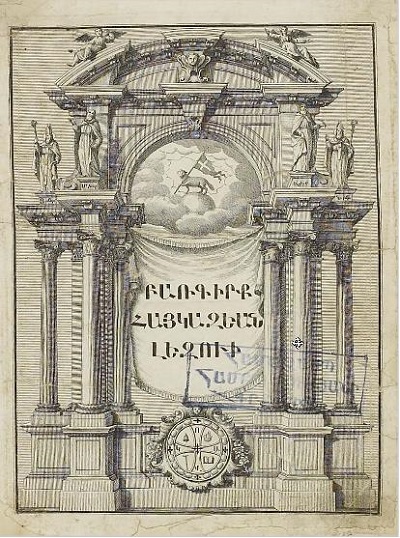

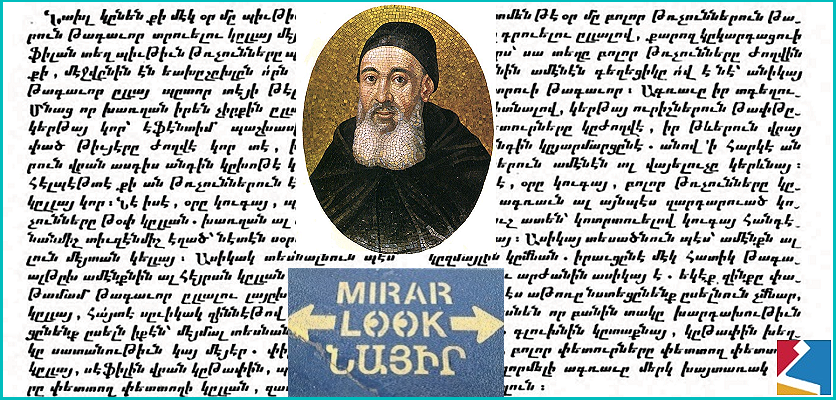

View of San Lazzaro degli Armeni in Venice, by Giuseppe Bernardino Bison (Photo: dorotheum.com)This long tradition of borrowing was first resisted by the Armenian Catholic Mekhitarist Congregation in Venice in the eighteenth century. This one-of-a-kind monastic order was founded in the early 1700s by the industrious Mekhitar of Sebastia and was deeply involved in life outside the monastery, including by opening schools, operating its own printing presses and writing religious, secular and linguistic works. In their dictionaries, grammars and schoolbooks, these learned monks first started framing the centuries-old, unproblematic acceptance of loanwords as an inherently misguided “mixing of languages,” fatefully applying the concept of linguistic purity to Armenian and laying the foundation for the purist language ideology that continues to reign to this day.

The Armenian Catholic Mekhitarist Congregation was founded in the early 1700s by the industrious Mekhitar of Sebastia (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The Armenian Catholic Mekhitarist Congregation was founded in the early 1700s by the industrious Mekhitar of Sebastia (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)One of the earliest and most intriguing examples of the rise of this new ideology came in 1769 with the second volume of the Mekhitarist Congregation’s magisterial Բառգիրք հայկազեան լեզուի (Dictionary of the Armenian Language). In this more than 1,500-page tome, we find two glossaries designed to help speakers banish their borrowings, each one duly marked with an asterisk to alert readers to its “foreign” (այլազգական) origin and to lead them to distinguish between “Armenian” and “non-Armenian” in a way that had never before been asked of them. Here we catch a glimpse of one of the earliest recorded instances of Armenians telling other Armenians how they should speak.

The Mekhitarist Congregation’s Dictionary of the Armenian Language (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The Mekhitarist Congregation’s Dictionary of the Armenian Language (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)Flipping through the pages of this volume, what stands out most to the contemporary reader is the overwhelming number of Turkish borrowings. This prevalence was at the time, and into the early twentieth century, considered one of the defining features of the spoken Armenian of Constantinople, the regional variety on which the glossaries were based. Given its status as a language of political and social power, it is far from unusual that Armenians in the Ottoman capital—many of whom were bilingual in Turkish—would integrate Turkish words into their spoken Armenian. This dynamic is not unlike Armenian Americans integrating words from English, their own language of political and social power. What is fascinating about these 1769 glossaries is that—although many borrowings have disappeared—others have escaped the pitchforks of purists and continue to be used by Armenian speakers today. These include common words like the following:

| Borrowing | Western Transliteration | Modern Turkish | English |

| Աֆէրիմ | Aferim | Aferim, aferin | Good job! |

| Պաճախ | Bajakh | Bacak | Leg, thigh |

| Խօշ | Khosh | Hoş | Nice, interesting |

| Ֆալան ֆիլան | Falan filan | Falan filan | Etcetera |

| Բապուճ | Pabouj | Pabuç | Slipper |

| Պէլքի | Belki | Belki | Maybe |

| Հայտէ | Haydeh | Haydi | Let’s go! |

| Թազէ | Tazeh | Taze | Fresh |

| Տէտէ | Dedeh | Dede | Grandpa |

| Տէրտ | Derd | Dert | Worry |

| Հայվան | Hayvan | Hayvan | Animal, brute |

The glossaries are also filled with food words, which still echo in Armenian kitchens today just as they did in 1769. Among them are:

| Borrowing | Western Transliteration | Modern Turkish | English |

| Խուրմայ | Khourma | Hurma | Date |

| Մաղտանոս | Maghdanos | Maydanoz | Parsley |

| Ֆստըխ | Fesdekh | Fıstık | Pistachio |

| Ֆասուլիայ | Fasoulia | Fasulye | Beans |

| Խըյար | Kheyar | Hıyar | Cucumber |

| Նանէ | Naneh | Nane | Mint |

Purity takes center stage in the nineteenth century

Similar glossaries of spoken language appeared over the course of the nineteenth century. We find an especially interesting one in 1847, complete with English definitions, compiled by an American Protestant missionary to the Ottoman Empire for a very special purpose: to help his fellow missionaries learn to speak casually with the Armenians they sought to convert. The vast majority of these lists, however, were designed to teach a purist language ideology to Armenian children, encouraging them to shed the Turkish words they used in everyday life. These are truly enthralling texts that show us the practical ways the seeds of this new ideology were first sown in the minds of the littlest Armenian speakers. Take, for example, the following passage from an alphabet primer published in 1825, which students were asked to sound out and read aloud as a kind of pledge:

Աշ-խար-հա-բառ խօ-սած ա-տե-նըս պէտք չէ՛ որ խօս-քիս մէ-ջը այ-լազ-գա-կան բա-ռեր խառ-նեմ, որ-պէս զի խօ-սած լե-զուս խառ-նած չըլլայ՝ հա-պա՝ մա-քուր ըլլայ։ Թէ որ բա-ռի մը աշ-խար-հա-բառը չեմ գի-տեր՝ պէտք է որ վար-պե-տիս հար-ցը-նեմ ու սոր-վիմ, որ աղէկ խօ-սիմ։

When I speak, I should not mix in fo-reign words, so that the lan-guage I am spea-king does not be-come mixed, so that it be-comes pure. If I do not know a word, I should ask my tea-cher and learn it so that I can speak pro-per-ly.

Similar attempts to curb the use of borrowings appeared and reappeared throughout the nineteenth century. Championed by new ranks of intellectuals in the Ottoman Empire, purism was particularly intense during the slow emergence of Standard Western Armenian, a new written language, based on the spoken language of Constantinople, that would rival and eventually overtake Classical Armenian in the final decades of the nineteenth century. The standardization of any language is often the product of decades-long, ideologically driven labor and stems from specific choices by individual people. It also is often much more effective at the level of writing than speaking. The case of Western Armenian is no different. Here we see this new written language come into being as a result of careful and deliberate engineering by a motley crew of intellectuals who all shared one common belief: that, no matter their prevalence in spoken language, Turkish borrowings should have no place in the new Western Armenian written standard. The architects of written Western Armenian were, in other words, staunch purists whose ideologies linger in the very way we are taught to use the language to this day. To get a sense of how their work led the spoken and the written to diverge, let’s take a look at a side-by-side comparison from 1843. Here we have the same passage in the spoken Armenian of Constantinople on the left and a “purified” form that today we would call Standard Western Armenian on the right:

.png)

Purity as a national duty

While by the end of the nineteenth century written Western Armenian had fully emerged as a paragon of purity, denuded of Turkish loanwords, the ideology had not succeeded in eliminating their use in conversation. By one estimate, around 1900, 4,200 Turkish borrowings were in common parlance among Armenians in Constantinople alongside 860 borrowings from European languages, especially from Italian and French. While Standard Western Armenian was very much closed to Turkish borrowings, a few European ones did manage to slip through the cracks. The following are the most commonly used in Western Armenian today:

| Borrowing | Western Transliteration | Source | English |

| Թէյ | Tey | Thé, from Chinese via French | Tea |

| Հորիզոն | Horizon | Horizon, from Greek via French | Horizon |

| Հերոս | Heros | Héros, from Greek via French | Hero |

| Մատիտ | Madid | Matita, from Italian | Pencil |

| Հայդուկ | Haytoug | Hajdúk, from Bulgarian | Fighter |

| Սկիւռ | Usgur | Skiouros, from Greek | Squirrel |

Why these borrowings were ushered into the Western Armenian standard when the following seemingly identical European borrowings—also used around 1900 in Constantinople—were barred entry is one of the inconsistencies in the logic of purists. These represent a group of borrowings called cultural loans, which do not replace older words but are instead adopted to describe newly introduced items or concepts, like many of the borrowings we use for new technologies today.

| Borrowing | Western Transliteration | Source | English |

| Տուշ | Dush | Douche, from French | Shower |

| Ֆանէլա | Fanela | Fanela, from Venetian | Undershirt |

| Սալաթա | Salata | Salata, from Venetian | Salad |

| Սալօն | Salon | Salon, from French or salone, from Italian | Sitting room |

| Թօռնօվիտա | Tornovida | Tornavite, from Italian (no longer used) | Screwdriver |

| Մօտա | Moda | Moda, from Italian | Fashion |

Classical Armenian is seen as the “purest” Armenian

In our discussion of purism thus far, we have neglected to address one essential question: if the concept of purity is premised on the idea that there was once a time when Armenian was pure, when was that time imagined to be? Almost universally, purists have considered the oldest Classical Armenian texts, dating to as early as the fifth century, to be fountains of the purest Armenian and have sought in them replacements for all kinds of borrowings. The Mekhitarists, in particular, spent decades combing through Classical Armenian manuscripts to retrieve these ancient words and put them into circulation through their dictionaries and grammars. While today’s purists are likely unaware that they are harkening all the way back to the earliest writings when, for example, they advise replacing your borrowings for cucumber and mint with the words վարունգ (varounk) and անանուխ (ananoukh), they are following in the footsteps of their eighteenth- and nineteenth-century counterparts, who were very vocal about their largely successful masterplan to draw Western Armenian vocabulary as close to Classical Armenian as possible.

The world had obviously changed quite a bit since the fifth century. In cases where words were needed for new items or concepts, Classical Armenian elements and word-building norms were used to create them. For example, when the potato—a vegetable native to the Americas—first appeared on Armenian dinner tables, intellectuals rejected the borrowing փաթաթէս (patates) in common parlance and instead coined the new word գետնախնձոր, using the Classical Armenian words գետին (kedin) and խնձոր (khntsor) and modeling it on the French pomme de terre, or “ground apple.” The same goes for new technologies, like the steamship (շոգի + նաւ= շոգենաւ) and the telephone (հեռու + ձայն= հեռաձայն). Standard Western Armenian bears the mark of this approach to this day, drawing on classical roots to create new words for modern inventions rather than rely on direct borrowings. Think համակարգիչ (hamagarkich) rather than just քոմբիւթըր (computer).

Just like today, in the nineteenth century these classical and classically inspired words needed to be taught to Armenians who only knew the borrowings. Imbued with the warmth of childhood and family life, these borrowings were not easy to excise from spoken language. Many had little sense that the words they had used all along were not Armenian by origin until they were told to abandon them. All the way back in 1847 some wondered aloud, for example, how they could ever possibly make their point without using կոր (gor), which started to be stigmatized around this time. While contemporary purists take to Instagram or to comments sections to preach purity, their nineteenth-century predecessors were more discreet, using the Classical Armenian word they sought to model in their writing while also including the more familiar Turkish word beside it for reference. This helped introduce classical words gradually without entirely disorienting the reader in the process. In the sample above, we see this technique in action in 1825.

For children just learning to read, purists sometimes opted for a visual strategy, as we see below in these images from an 1836 alphabet book.

Armenians have always borrowed

There is, however, one ironic twist in this nineteenth-century purist campaign and in the work of purists today: many of the Classical Armenian words touted as “pure” were once themselves…borrowed. Achieving purity is only ever an ideal, a myth, an impossibility in regions of the world where cultural contact has been ever-present. Classical Armenian did not escape this contact; it was built by it. Much of its lexicon, down to some of its most basic vocabulary, was borrowed from other languages of the region. Consistently turning to Classical Armenian to replace borrowings in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries means that many of these historic borrowings made their way into Standard Western Armenian and are still the building blocks of the language today.

Again, we turn to Hratchia Adjarian, whose Հայոց լեզվի պատմություն (History of the Armenian Language) is a veritable survey of language contact throughout the ages. From his syntheses of research into Armenian word origins, we see that a set of Iranian languages (Parthian, Middle Persian, etc.), Greek and Syriac most fundamentally shaped the vocabulary of Classical Armenian. These were languages of prestige and power when Classical Armenian was first used in writing in the fifth century. By that time, these borrowings had replaced indigenous Armenian words, the vast majority of which were never recorded and have thus disappeared without a trace. Borrowings from Iranian languages in particular were so pervasive that Armenian was once considered a part of the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family.

These historical borrowings should in no way be misunderstood as “not Armenian” today. Like most languages around the world, Armenian is at its core a unique blend of influences. While many words originated in other languages, they have been made Armenian through more than a millennium of use by Armenians. Would we argue that the words art and dance are “not English” today because they entered English from French and French from Latin centuries ago? Of course not. We should see the sample of Classical Armenian and Standard Western Armenian words below—and the thousands of others like them—through the same lens.

| Armenian Word | Western Transliteration | English | Source Language Family |

| Ճերմակ | Jermag | White | Iranian |

| Շապիկ | Shabig | Shirt | Iranian |

| Հազար | Hazar | Thousand | Iranian |

| Բրինձ | Prints | Rice | Iranian |

| Բժիշկ | Pjishg | Doctor | Iranian |

| Դժուար | Tjvar | Difficult | Iranian |

| Պանիր | Banir | Cheese | Iranian |

| Armenian Word | Western Transliteration | English | Source Language |

| Շուշան | Shushan | Lily | Syriac |

| Տղայ | Dgha | Boy | Syriac |

| Քահանայ | Kahana | Priest | Syriac |

| Մազ | Maz | Hair | Syriac |

| Տերեւ | Derev | Leaf | Syriac |

| Շաբաթ | Shapat | Saturday, week | Syriac |

| Խանութ | Khanout | Store, shop | Syriac |

| Armenian Word | Western Transliteration | English | Source Language |

| Գաւաթ | Kavat | Cup | Greek |

| Եկեղեցի | Yegeghetsi | Church | Greek |

| Պնակ | Bnag | Plate | Greek |

| Կիրակի | Giragi | Sunday | Greek |

| Ստամոքս | Sdamoks | Stomach | Greek |

| Թատրոն | Tadron | Theater | Greek |

| Կեռաս | Geras | Cherry | Greek |

Clearly early Armenian writers did not share our modern purist language ideology. The nineteenth-century grammarian Arsen Aydenian summed it up best in 1866 when he quipped that “our ancestors did not loathe foreign words nearly as much as we do today.” In less than a century, an explicitly purist campaign managed to swiftly change attitudes toward borrowings and instill a new, ever-present concern for purity. It is the legacy of this concern that we live with today. A major result of this campaign was the distancing of spoken language from written language. While spoken Western Armenian still retains many of the Turkish borrowings that purists strived to banish, written Western Armenian bears their everlasting imprint. Whether spoken or written, Western Armenian today still very much exists within this paradigm of purism. There is still a sense of deference to a formal, classically-inspired kind of language, still an unease about borrowings, still an interest in separating the “pure” from the “impure.” While Turkish is no longer the major source of new loanwords into Armenian, the other dominant languages of the diaspora have taken its place and have been stirring a similar kind of anxiety about language for more than a century. Given this reality, our purist language ideology today is not at all surprising. Around the world, purism is a common reaction to anxiety or insecurity about the future of a language. The Mekhitarists felt this insecurity and invented this ideology in an attempt to protect Armenian and ensure its longevity. More than two centuries later, many Armenians in this day and age are motivated by the same instinct to protect. Following in the footsteps of generations of purists before them, they perpetuate purism in reaction to the similar linguistic realities faced throughout the diaspora, keeping the ideology firmly intact.

Purity today and into the future

But this particular approach to borrowings does not need to be propagated if we find that it is no longer serving us as speakers. Rather than continuing the legacy of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century purists, we can choose to take the earliest Armenian writers as examples, writers who did not treat borrowings as sources of contamination but readily adopted them where they saw fit. Like them, we can choose to accept borrowings as ordinary elements of spoken languages wielded by multilingual people in touch with the cultures around them rather than demons to ward off.

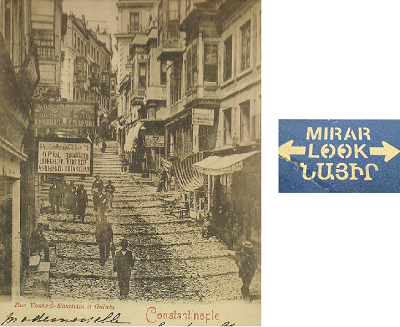

Multilingual Istanbul and multilingual Los Angeles.

Multilingual Istanbul and multilingual Los Angeles.This is not a call to begin using modern borrowings in standard written Western Armenian. This form of the language came into being through puristic labor. Continuing to write the way purists had intended, complete with the classical and classically inspired words they infused into the standard, is not a crime but an homage to critical figures in the formation of the language. Rather, this is a call to loosen the grip of purism over spoken Armenian in particular and reconsider whether we want to allow this ideology to dictate how we speak in all contexts.

The reality is that over the past two centuries Armenians have been expected more and more to speak the language of writing. As we have seen, this expectation is historically unprecedented. This relatively new trend has erased awareness of the age-old history of borrowings in spoken Armenian and has vilified what had long been ordinary. Such vilification is not without consequences. Relentlessly pursuing purity and holding it up as a cultural ideal can foster deep insecurities and shame in Armenian speakers, leading many to constantly fret that they are not speaking “correctly.” It can also inhibit expression and push people away from Armenian entirely. Having turned borrowing into a cause for reproach, this ideology has particularly dire consequences for the large number of diasporans today who have not had the opportunity to be formally educated in Armenian. Already lacking confidence in the language, they may choose to abandon it altogether after being told one too many times that the words they have learned at home from their parents and grandparents are “not Armenian.” The same goes for speakers who are looked at disapprovingly for peppering their Armenian with English words. Why bother trying, they may ultimately ask in exasperation.

There is no reason why various forms of Armenian cannot coexist, no reason why written and spoken language need to be held to the same standard, no reason why purism needs to loom large in every social interaction. Already small cracks have begun to appear in this ideology. These cracks expose efforts to reverse the stifling effects of purism on spoken language. One of the best examples is Aghvor paner, an initiative that gives value to spoken forms of Armenian, complete with their borrowings, and gives voice to words and expressions that have been overridden in standard written language. Its work frames borrowings as sources of richness and pokes fun at, rather than encourages, attempts to erase them.

This reframing can guide us toward beginning to think of borrowings in Armenian as tools, tools not just for understanding the lives of Armenian speakers throughout the ages but also for understanding the waves of cultural contact that have shaped our own individual family histories. A sprinkling of English words here, a smattering of French words there, a dusting of Arabic words over the top can tell us about the multilayered pasts and circuitous trajectories that have brought us to where we are today. Breaking free of a purist language ideology can allow us to see our own borrowings as the outermost rings of a tree trunk, each one keeping a record of the distinct phases in the history of Armenian and its speakers.

Are you an aspiring writer, poet, or artist? Show the world what you've got!

Join our community and receive regular updates!

Join now!

Attention!